When people think of the historical “Celts,” they are really thinking of the various peoples that lived across the European continent adjacent to the ancient Greeks and Romans and in Britain during the Iron Age who belonged to the La Tène culture. “La Tène” refers to the last stage of the pre-Roman Celtic Iron Age leading up to Julius Caesar’s conquests. It is the period of Celtic history that saw the true emergence of a distinct Celtic artistic style. The La Tène cultural period saw a great shift for Celtic peoples as they experienced new settlement patterns, militaristic gains, and significant advancement in metalworking and other art forms.

When Was the La Tène Period?

The La Tène cultural period lasted from approximately 450 BCE-43 CE, when the Roman emperor Claudius launched an invasion of Britain that led to a successful Roman conquest. It emerged from the earlier Hallstatt Celtic culture and reached its peak during the expansion of Celtic power and influence in the 4th century BCE. La Tène culture began its decline on the continent after Caesar’s Gallic Wars (58-50 CE) and the subsequent Roman conquest of Gaul, a major area for Celtic communities during the Iron Age. It completely faded out during the settlement of Roman Britain (43-410 CE), at which point Celtic culture in Britain shifted into what historians refer to as the Romano-British phase.

The culture gets its name from a site of the same name on Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland, where the first La Tène objects were discovered in 1858. The finds consisted of the remains of a wooden iron age bridge or jetty and 116 swords, 270 spears, wooden wheels, shields, axes, and domestic tools. The discovery of these objects revolutionized the popular view of the historical Celts at the time. The quality of the craftsmanship reflected an intricacy not previously attributed to Celtic artisans.

The large number of objects in the Lake Neuchâtel hoard led archeologists to believe that there may have been a ritual element to their deposition. As such, these 19th century finds helped begin to piece together the puzzle of who the La Tène Celts were. It revealed much about what they made, what their ritual practices looked like, and how they created communities for themselves.

Who Were the La Tène Celts?

The La Tène Celts occupied a wide area of land across the European continent during the Iron Age. The earlier Hallstatt civilization was centered along the Upper Danube in Austria, but during the late 6th and 5th centuries BCE, Celtic communities had shifted towards the Rhine. By 450 BCE, the commonly accepted “starting point” of the La Tène cultural period, these communities had shifted even further north of the Alps in Switzerland and eastern France. By this time, Celtic migrations and trade missions had also established occupations in Spain, Britain and Ireland. Eventually, the heartland of La Tène Celtic culture became Gaul.

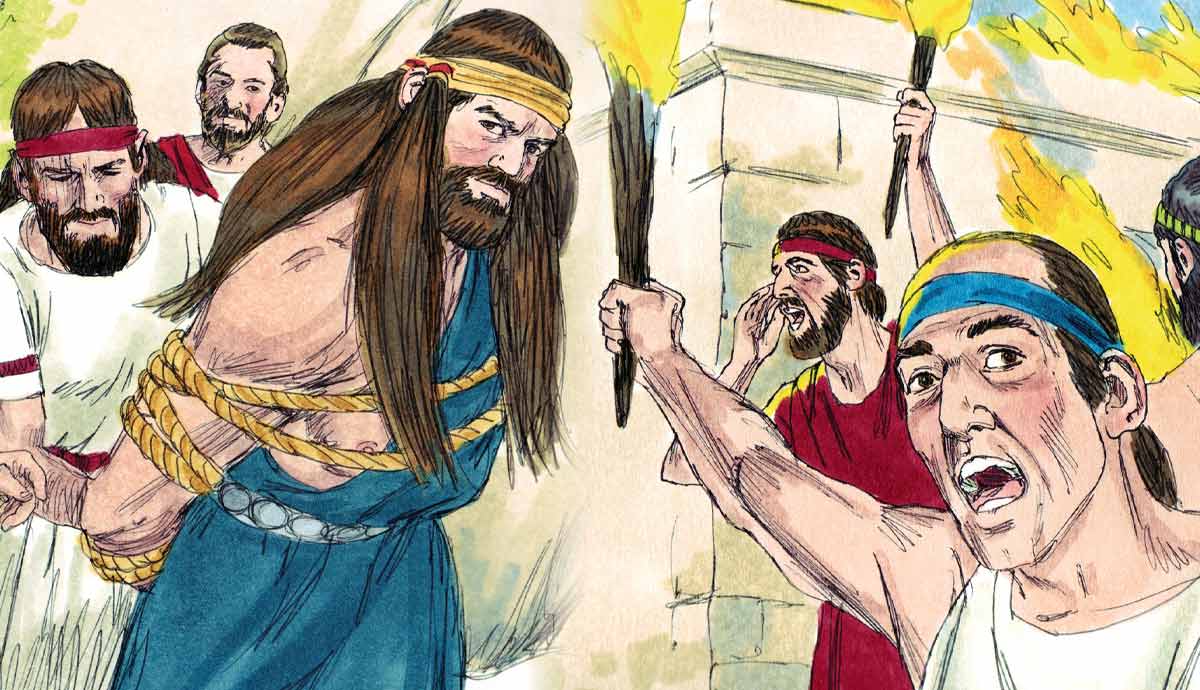

The La Tène Celts were militaristically advanced and seemed more interested in geographical expansion than their Hallstatt predecessors. Over the next several hundred years, various Celtic peoples invaded southern France and northern Italy, with some invasions reaching as far as Macedonia and Greece. The La Tène Celts expanded further north into Britain and Ireland towards the end of their cultural period, but had well-established linguistic and artistic traditions on the islands by the time of the Roman conquest of Britain.

What We Know About the La Tène Period

What we know about the La Tène culture and period comes largely from archeological evidence and from ancient Greek and Roman literary sources. Classical textual sources must, however, be taken with a grain of salt. Ancient Greek and Roman writers often recorded accounts of their barbarian neighbors with the primary intention of “othering” them to their audiences, and with a secondary intention of furthering the imperial project and justifying expansion into the continent. This expansion would lead to the conquering and subjugation of a wide variety of Celtic communities, particularly on the continent.

Ancient Greek and Roman writings on Celtic peoples from this period, therefore, are often negative descriptions. For instance, Strabo wrote:

“To the frankness and high spiritedness of their temperament must be added the traits of childish boastfulness and love of decoration. They wear ornaments of gold, torques on their necks, and bracelets on their arms and wrists, while people of high rank wear dyed garments besprinkled with gold. It is this vanity which makes them unbearable in victory.”

Through this characterization, the Celts are painted as more ostentatious, vain, and childish than their seemingly more civilized Roman neighbors. Julius Caesar offered an even more detailed description in his Gallic Wars:

“The most civilized of all these nations are they who inhabit Kent, which is entirely a maritime district, nor do they differ much from the Gallic customs. Most of the inland inhabitants do not sow corn, but live on milk and flesh, and are clad with skins. All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which occasions a bluish color, and thereby have a more terrible appearance in fight. They wear their hair long, and have every part of their body shaved except their head and upper lip.”

Caesar’s description implies a variety of differences between the various Celtic peoples and the ancient Romans: dietary differences, a customary practice of tattooing, and differences in hair styles. His account, while comprehensive, thoroughly portrays the Celts as inferior.

Archeological Evidence

There are not many extant graves from Iron Age Britain, which provides a challenge for archeologists. The majority of La Tène objects have been found in dry land hoards or in wet contexts—such as rivers or lakes—so they lack the contextual details that grave goods possess. These objects, however, can provide much information about La Tène Celtic religious customs.

If these hoards and other clusters of objects were not grave goods, archeologists have reasonably assumed that they were part of a ritual deposition practice. These objects were likely placed in land or water intentionally as offerings to the Celtic gods. Consider, for example, the Lake Neuchâtel hoard that gave this cultural period its name. It is likely that the hundreds of swords and spears that were deposited in the lake were put there as an act of worship to a deity presiding over the sacred waters of the lake.

Other important military objects, like Celtic ring-necklaces and status symbols known as torcs, have been found in Celtic waterways like the River Thames. That torcs were likely offered as gifts to supernatural beings suggests a wider symbolism associated with prestige and power in Celtic society.

The few La Tène graves that have been discovered have offered archeologists useful information about Celtic society, particularly through the shift to chariot burials. In the earlier Hallstatt period, the bodies of the elite were interred in four-wheeled wagons. La Tène elite burials, by contrast, involved two-wheeled chariots. While the wagons of the Hallstatt period suggested that the early Celts were a farming-based culture, the shift to chariots indicated an increasingly militaristic society, and one whose elite prided themselves on success in battle. It should be noted that most archeological evidence from graves can only speak to the experiences of the elite members of Celtic society that could afford such lavish funerary arrangements.

The Flourishing of Celtic Art

La Tène culture saw the emergence of a distinctly Celtic art style. In this period, jewelry and decorated weapons involved increasingly elaborate manufacturing processes and displayed an intricacy and creativity not present during the Hallstatt period.

There has been some debate over how “original” Celtic art is. Some historians have argued that Celtic art was almost wholly developed out of Etruscan art and Hellenistic Greek art that the early Celts had access to through imported objects like amphora. Other historians have argued that Celtic art possessed an original genesis but that, like many other cultures throughout history, artisans absorbed influences from other cultures. This belief complements what archeologists know: that Celtic peoples were travelers and had established trade networks.

Celtic art virtually vanished on the mainland continent after the Roman conquest of Gaul in the mid-1st century BCE, but it continued and developed further in Britain and Ireland. Between 250-650 CE in the British Isles, Celtic art occurred predominantly on cast bronze objects and clothing fasteners like penannular brooches and pins.

Celtic material culture has historically not been considered “art,” largely due to the functionality of Celtic art objects. Most objects that are now considered Celtic “art” were primarily created for everyday or military use, like brooches, torcs, shields, and swords. In the La Tène cultural period, however, these objects became more ornamental and decorative. Therefore, while still not necessarily being “art for art’s sake,” or objects created for the sole purpose of appreciating their beauty, there was a greater attention paid to aesthetics in the La Tène culture than was given to objects in the Hallstatt culture.

Some other examples of functional Celtic art objects were those objects created expressly for ritual purposes, such as the phenomenon of Celtic sculpted heads. Ancient Greek and Roman writers recorded that Iron Age Celtic peoples participated in ritualized practices of human headhunting and head collecting. The archeological record also reflects that they practiced head worship. Objects like the Mšecké Žehrovice Head, a life-sized sculpted depiction of a human head shown above, have been found in enclosures at La Tène settlements that are believed to have been intended for ritual.

Did the La Tène Culture Mark a Shift in Celtic Art?

It is safe to say that yes, the La Tène culture marked a true shift in Celtic art. This period saw shifts in art style, in funerary art practice, and in attention to aesthetics. The La Tène culture produced the pinnacle of distinctly Celtic art, which later transitioned into the insular art styles of early medieval Britain and Ireland.

The construction of graves and grave goods for elite burials reflected changing aspects of Celtic society, such as the shift from a primarily farm-based economy to one based on militaristic expansion. This period also saw the first real attention that Celtic artisans paid to rendering the human form, through the tradition of producing sculpted heads to stand in place of real human heads for ritual practice. Therefore, it can safely be argued that the La Tène culture led to, and can be characterized by, the flourishing of Celtic art.