Did you know that none of the paintings attributed to Leonardo da Vinci are signed? Our modern idea of art assumes that an artist paints whatever he chooses and adds his name to the finished result. Such a practice would have been unthinkable in Leonardo’s time when images were commissioned to decorate churches or palaces. The rare exception to that rule was when artists ‘signed’ through self-portraits. Sometimes an occasional bold artist, like young Michelangelo, had the audacity to carve his name on his marble Pietà.

The Rarity of Leonardo da Vinci’s Paintings

This is why only about fifteen paintings are widely acknowledged as being painted by Leonardo. Others are subject to scholarly debate, which attempts to assess if the work was done by the master himself, by his assistants or perhaps are among the numerous copies of his highly influential works.

To illustrate the point, one just has to consider the astonishing jump in value of Salvator Mundi. It was first thought to be a copy of the work of one of Leonardo’s assistants. It was eventually sold at auction for a record sum of $450.3 million as being painted by Leonardo’s own hand. With such a small number of genuine Leonardo da Vinci paintings in existence, the Louvre with five of those paintings is the number one destination for admirers of Leonardo da Vinci.

An Art History Tour De Force

For ten years, two curators from the Louvre, Vincent Delieuvin and Louis Frank, worked on an exhibition worthy of the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death. Their first accomplishment was to gather into one exhibition two-thirds of the surviving paintings. Totaling over 160 pieces, this was the only occasion in our own lifetimes that so many masterpieces would be displayed in one place.

Even the absent paintings were present through at-scale infrared photographs acting as replacements. All the documents except about two major lost paintings, the Anghiari Battle and Leda were present. Virtually all of Leonardo da Vinci’s artistic achievements were in the exhibition. An unprecedented art history accomplishment.

Furthermore, the curators avoided a chronological display by organizing the displays around themes: Light, Shade and Relief; Freedom; and Science.

Light, Shade, Relief

The exhibition starts with a bronze statue by Leonardo’s master Verrocchio, and a display of young Leonardo’s studies of shade on drapery. The visitor discovers how his use of shading to create the sensation of three dimensions on a flat surface would become significant for the rest of his career.

Freedom

Eventually, Leonardo’s sketched studies were repeatedly reworked to the point that the figures ended up looking like dark and muddled shapes. This unique freehand drawing style was named by Leonardo as “componimento inculto”, meaning “instinctive, intuitive composition”, hence the curators’ ‘Freedom’ category.

To explain what he meant, Leonardo asked “have you never considered how the poets composing their verses do not trouble themselves to write beautifully, and do not mind crossing out some of those verses, rewriting them better?”. Further illustrating how he found inspiration, he said: “I have seen clouds and wall stains which have inspired me to beautiful inventions of other things”. Leonardo’s freehand resulted in an entirely unique drawing style, even at the risk of leaving a painting unfinished.

With Saint Jerome, the unfinished state of the painting helped the viewer understand the sfumato technique. By repeatedly adding layers of translucent light greys until their accumulation made the greys darker and shading swirling-like smoke on flesh and clothing, he thereby creates volume with an extraordinary smooth transition between light and shadow.

of the three-dimensional volume thanks to the sfumato effect.

For this effect, Leonardo abandoned the mixture of egg yolk and pigment, which had been used until then for oil paint. However, instead of being opaque, oil allowed for transparency effects, which were elevated to unprecedented levels with the sfumato, a ‘transparent smokiness’. Or in Leonardo’s own words, “light and shade blend without strokes and borders looking like smoke”.

Science

“I have seen clouds and wall stains which have inspired me to beautiful inventions of other things”

In the Science themed section, the visitor discovered an extraordinary concentration of scientific sketches and books, nearly half of the surviving notebooks of Leonardo. On the pages they could see a reflection of the workings of Leonardo’s mind: mathematics, architecture, the flight of birds, anatomy, engineering, optics, and astronomy.

In the words of his biographer, “[Leonardo’s] enquiries into natural phenomena led him to understand the properties of herbs and to continue his observations of the motions of the heavens, the course of the moon, and the movements of the sun”. The drawback to such curiosity was that “he set about learning many things and, once begun, he would then abandon them”.

Although Leonardo might have been an illegitimate son who only received two years of formal education, his inquisitive and creative mind was unlike any other artist or engineer of his era. He was a “disciple of experience”, who learned by observing the flow of water, the birds in the sky and the shapes of the clouds.

Even when his contemporaries could see he was an incredibly creative engineer, however, they still thought his ideas were too far-fetched. An illustration of this lack of acceptance of Leonardo’s unorthodox ideas was apparent when “he showed the many intelligent citizens then ruling Florence how he wanted to raise and place steps under the church of San Giovanni without destroying it”. While “he persuaded them with such sound arguments that they thought it possible, when they left Leonardo’s company, each would realize by himself the impossibility of such an enterprise”.

Leonardo’s biographer stated that “his hand could not reach artistic perfection in the works he conceived, since he envisioned such subtle, marvelous, and difficult problems that his hands, while extremely skillful, were incapable of ever realizing them”. The graceful wonders that inhabited his mind forever vanished the day in 1519 when Leonardo died.

Five centuries later, however, by organizing and displaying the greatest concentration of Leonardo’s masterpieces in memory, the Louvre exhibition did everything possible to help us envision Leonardo’s subtle and marvelous artworks.

The first original painting in the exhibition, the Benois Madonna, a Virgin Mary smiling lovingly at her son, illustrated how the smile became a thread throughout Leonardo’s career.

“I can do everything possible as well as any other”

Next, the exhibition visitor travels to Milan and into the period when Leonardo did something highly unusual for his time. He wrote to the Duke of Milan in search of employment and offered ten points of detailed descriptions of the instruments of war he could create.

With the tenth point, after suggesting he could help destroy things, talks about building them, for “times of peace”. Leonardo assured the Duke that “I can give as complete satisfaction as any other in the field of architecture, and the construction of both public and private buildings, and in conducting water from one place to another”. Then he proposed to create marble and bronze sculptures. His very last point noted that “in painting, I can do everything possible as well as any other, whosoever he may be”.

The Last Supper obviously cannot be moved to the exhibition, yet we were transported in time to the state Leonardo left it before five centuries of decay did its merciless work. With the most important contemporary copy, painted in oil by Leonardo’s own assistant, we saw the Last Supper as Leonardo left it 520 years ago.

The Louvre’s Virgin of the Rocks, one of the most influential paintings of the Renaissance, is a most resounding illustration that, indeed, Leonardo could “do everything possible as well as any other, whosoever he may be”.

Yet because the priests who had commissioned Leonardo were unhappy with the painting, there were years of litigation, when the artist had to defend his work. In his defense, Leonardo explained that the monks “are not expert in such matters, and that the blind cannot judge colors”. Leonardo also had issues with the monk in charge of the refectory where the Last Supper was painted. That monk complained that he could not understand “how Leonardo sometimes passed half a day at a time lost in thought.” This prompted Leonardo to defend himself by saying “the greatest geniuses sometimes accomplish more when they work less, since they are searching for inventions in their minds”.

Scholarly Games

The exhibition visitor could also engage in the scholarly game of guessing which works might be by Leonardo and which might be by his assistants. First, the curators drew attention to a selection of portraits done by Leonardo’s assistants – people who were good enough to be employed by Leonardo and who learned from him the sfumato technique. A fair comparison, same tools, same place and time.

So with the two versions of the Madonna of the Yarnwinder, one restored and the other still partly hidden behind yellowed varnish, visitors could observe the faces, eyes and hands, as well as the backgrounds and try to guess which was good enough to have been done by Leonardo’s hand.

Leonardo’s Lost Masterpieces

Even two masterpieces lost or destroyed were present. The first one was subject to the greatest artistic contest in history. In the same room at Florence’s City Hall, Leonardo was on one side and Michelangelo on the other. They were tasked to paint battle scenes illustrating the glories of Florence. Both geniuses abandoned, leaving their work unfinished, later painted over, forever lost.

The Louvre’s exhibition included all the major documents and sketches for Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari and Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina. A copy of Leonardo’s unfinished masterpiece reworked by none other than Rubens, was a reminder that Leonardo wasn’t just influential in his own lifetime but that he still is five centuries later.

The curators obtained and displayed the best painted copy in existence of the nude Leda. Along with the majority of the Leda sketches, they added two Roman marble copies of the lost Greek nude Aphrodites.

A Genius At His Peak: The Scapigliata and Saint Anne

The public was then treated to a rarely seen Leonardo treasure, the Scapigliata, a marvelous painted study of a smiling disheveled woman. We know close to nothing about this work – was it a study for Leda, or was it an invention? This enigmatic and dreamy face made it difficult to hope for more wonders.

And yet there was another striking wonder with the two Saint Anne masterpieces. The Louvre painting and the Burlington cartoon from the National Gallery of London, together in the same room for only the second time in 500 years. First, the visitor was reminded of the rarity of the cartoon. It was a preparatory sketch for a painting, in that there are only two Leonardo cartoons extant, and both were at the exhibition.

Leonardo’s biography mentions that “he did a cartoon showing Our Lady and Saint Anne with the figure of Christ, which not only amazed all the artisans but, once completed and set up in a room, brought men, women, young and old to see it for two days as if they were going to a solemn festival in order to gaze upon the marvels of Leonardo which [had] stupefied the entire populace”.

Good enough to stupefy Renaissance Florence, this cartoon and the sketches represent the nearly twenty years of work Leonardo put into the Saint Anne painting. To illustrate the impact of this masterpiece, of all the artworks on display at the Louvre, this is the only one that often makes visitors weep because of elicited emotion.

This effect can only happen if the viewer looks intently, joining the eye exchange between the three figures, Saint Anne, her daughter Mary, and young grandchild Christ. Even if none of them are looking at us, and the eyes of the grandmother are actually invisible, still the eyes, faces and smiles express the universal language of love, tenderness and family affection.

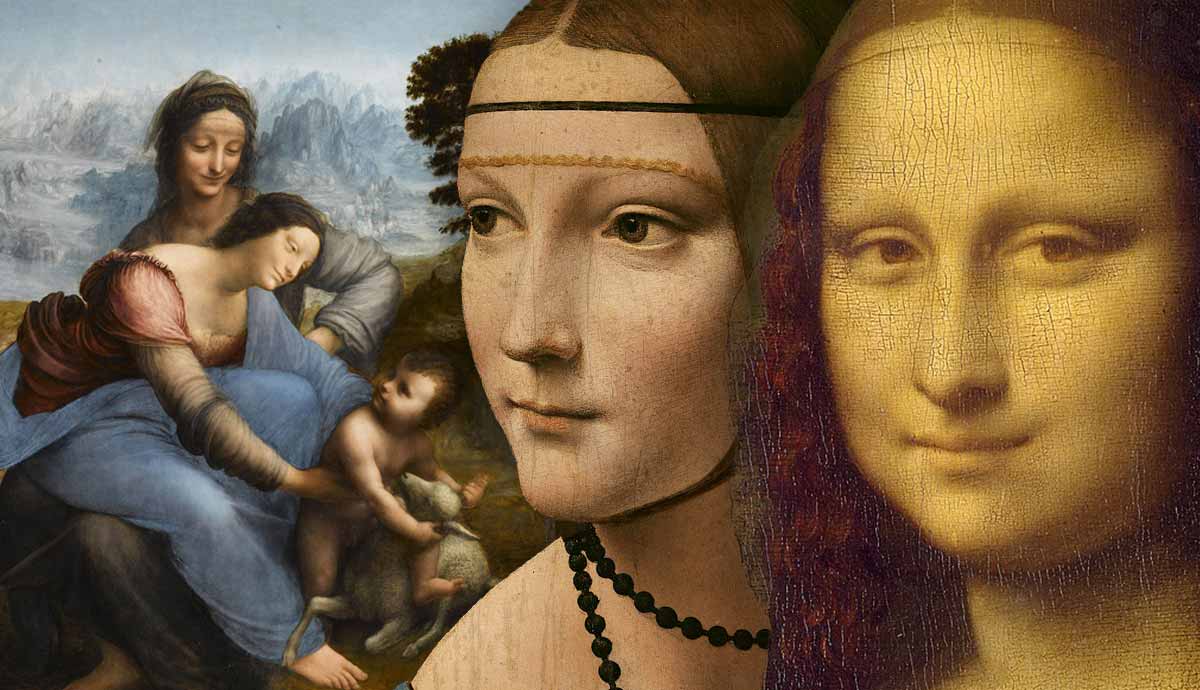

Through the Benois Madonna, the Virgin of the Rocks, Leda, la Scapigliata, the two Saint Annes, and John the Baptist comes the realization that Leonardo painted smiles, again and again. His biographer noted of the smiles and joy that “such considerations had their origin in Leonardo’s intellect and genius”.

The Louvre exhibition clearly helped visitors understand what made Leonardo da Vinci’s art unique: the shadows and smiles; his most subtle and free hand, tied to his uniquely curious and inventive mind; and the never-ending refinement of his works which led to an incompleteness and rarity of his work.

Even though his scientific and engineering prowess was too far-fetched for his time, and despite many of his notebooks and papers being lost and left unpublished, Leonardo’s scientific curiosity wasn’t entirely wasted.

The Science of Painting Allowed Leonardo to Express the “Mental Movements” of the Human Figure

The sense of inquiry that prompted him to open corpses not only helped Leonardo understand how blood streams into the body but also how water flows downriver and birds fly. His vast accumulation of scientific knowledge, coupled with his study of the natural world, allowed Leonardo to attain the science of art.

Leonardo explained this convergence of science and art: “painting is the sole imitator of all the manifest works of nature”, as it is “a subtle invention which considers all forms: sea, land, trees, animals, grasses, flowers, all of which are enveloped in light and shade”. Painting is “science, therefore, we may justly speak of it as the granddaughter of nature and as the kin of god”. The science of painting allowed Leonardo to express the “mental movements” of the human figure.

The result, Louvre curators explained, was that “his contemporaries saw Leonardo as the forerunner of the ‘modern style’ because he was the first (and probably only) artist capable of endowing his work with an awe-inspiring realism”. The original French text is even more powerful, stating that Leonardo “gave the fearsome presence of life to painting”.

The curators go on to assert that “such creative power was as overwhelming as the world inhabited by Leonardo – a world of impermanence, universal destruction, tempests and darkness”. Ten years of intimacy with Leonardo da Vinci’s creative spirit left the curators in a state of poetic wonderment. A feeling shared by many visitors, leaving the Louvre bewildered and astonished, some even with a tear in their eye.

Sources

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

- Leonardo da Vinci, Treatise on Painting, and Leonardo da Vinci, letter to Ludovico Sforza, offering his services, circa 1482; letter to Ludovico Sforza, complaining about pay for the Virgin of the Rocks, circa 1494. In LEONARDO on painting, Edited by Martin Kemp.

- Vincent Delieuvin, Louis Frank, Léonard de Vinci, Louvre éditions, 2019

- Burlington Cartoon & Vasari’s description of a cartoon that “stupefied the entire populace” : there may have been several cartoons made but only one that survived, so it is not certain that the one extant is the one displayed to the Florentine public.