Leonora Carrington was a British-Mexican artist who, during her vibrant 94 years of life, was associated with the Surrealist movement, and lived and worked as an artist amidst the exciting 20th-century art scenes in London, Paris, and Mexico City. From her birth in 1917 in England to her death in 2011 in Mexico, the Surrealist painter never stopped pushing the boundaries of art, gender, spirituality, and her own imagination. Although today many appreciators of Surrealist art have not heard her name, Leonora Carrington was a powerful force within and outside of the famous art movement. Keep reading to learn more about the Surrealist artist’s colorful life and nearly-century-long career.

Leonora Carrington Rebelled Against Her Traditional Upbringing

Not long after Leonora Carrington was born into an upper-class English family in Lancashire, she began boldly rebelling against the stiff culture and societal expectations prescribed to privileged young women like her. As a teenager, Carrington was expelled from two different private schools, as she was more interested in studying fantasy and fables than participating in debutante balls and religious activities.

The Surrealist painter’s early love of English writers like Lewis Carroll and Beatrix Potter, who wrote fantastical tales about animals, influenced her throughout her life. These interests paved the way for her to discover Surrealism and, despite disapproval from her family and community, pursue life on the fringes of high society as a Surrealist painter.

Leonora Carrington and Surrealism

Surrealism is an avant-garde art movement that developed alongside Sigmund Freud’s theories of psychoanalysis between World War I and World War II. Surrealist painters like Carrington explored the unconscious mind—resulting in wildly expressive, dreamlike, and sometimes unsettling images. At age 19, Leonora Carrington visited the first International Surrealist Exhibition in London, where she was captivated by the fascinating art and ideologies of the new movement. Carrington especially liked the work of Surrealist painter Max Ernst and was drawn to his famously haunting 1924 painting Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale.

Soon, Carrington formed a romantic relationship and headed to Paris with the 46-year-old Ernst, which caused her family to disown her. She spent time associating with Ernst’s circle of Surrealist friends in Paris but was not fully embraced by the Surrealist movement, which was often problematic for women artists. Her relationship with Ernst ended within a few years.

Women Surrealist Painters

Although Leonora Carrington and other women artists embraced many tenets of Surrealism, as an art movement, it did not make adequate space for women artists to be equal to their male counterparts. Because many men tended to espouse Freud’s problematic ideas about women and their supposed inferiority, women in Surrealist circles struggled to be seen as more than muses for male artists. Like she did as a child, Carrington rebelled against this limiting expectation, too, and said, “I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse. I was too careful rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.” Carrington felt empowered to assert her individual femininity and sexuality in her work through her own lens rather than that of a male artist.

While Carrington was drawn towards Surrealism throughout her career, she interacted with the art movement and its participants on her own terms—both due to her gender and her staunch individuality as an artist. Unlike many Surrealist painters, Carrington did not latch tightly onto the writings of Freud. Instead, she was more focused on exploring her own autobiography, including her personal interpretation of dreams, spirituality, sexuality, and her growing interest in alchemy and magical realism.

In addition to utilizing the tenets of the Surrealist movement, Carrington also continued to draw upon the English fairy tales she enjoyed in childhood and explore the depths of her own imagination. Her art was, of course, informed by the theories of the unconscious mind that were omnipresent in the early 20th century, but she also developed her own understanding of these ideas and how to express them, and the complexities of the female form and experience, in an individualistic and empowered way.

Leonora Carrington’s Imaginary Iconography

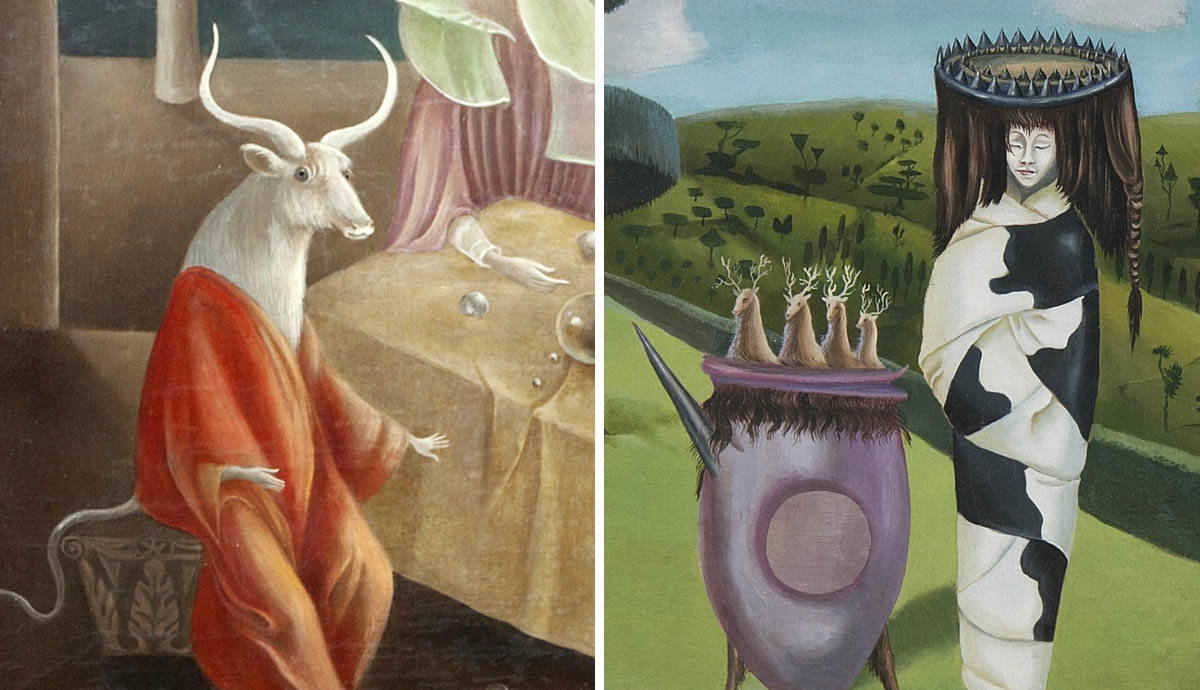

Strange creatures populate Leonora Carrington’s canvases, from menacing minotaurs to diminutive dogs, and powerful goddesses to solemn children. Carrington would use small brushstrokes to carefully build layers of paint, facilitating the rich level of detail required to contain her fascinating, symbolic concepts. Always fascinated by the artistic and psychological potential of animal subjects, Carrington sometimes subtly entered herself into her compositions in the form of a white horse.

Like many Surrealist painters, Carrington was inspired by the uncanny art of 15th-century Netherlandish artist Hieronymous Bosch, who has been famous for centuries for his highly detailed, fantastical, and sometimes macabre paintings that are always stuffed to the brim with imaginary creatures. Bosch’s remarkable ability to combine biblical, folkloric and totally original references into a singular dynamic composition would have fascinated Carrington, who frequently attempted the same feat in her work.

Carrington honed her individualistic Surrealist painting style by combining her fascinations with nondenominational spirituality, Surrealism, and psychoanalysis with her interest in magic realism. The genre of magic realism originated in German literature in the 1920s and sought to creatively blur the line between reality and fantasy. Carrington explored the potential of magic realism in her own work by adding fantastical elements and nightmarish creatures to otherwise ordinary situations and realistic scenery, creating a thought-provoking, dreamlike effect.

Moving From Europe to Mexico

In the 1940s, amidst the rising Nazi occupation in Europe, Leonora Carrington moved to Mexico City after suffering a series of mental health setbacks. Compared to high society England, the novel culture and more favorable climate of Mexico reinvigorated Leonora Carrington’s creativity. There, she painted, sculpted, and published books. She became something of a celebrity and, in 1947, was the only English woman invited to show work in an international Surrealist exhibition in New York.

Living in Mexico City exposed Carrington to countless new ideas, hobbies, and practices. She studied the writings of the ancient Maya, including the Popul Vuh, a sacred text about the K’iche’ people that fanned the flame of her passions for mythology and alchemy. She also took up cooking, having felt inspired by the healing power and alchemical transformation she saw represented in traditional Mexican food and kitchens. In the 1950s and 60s, Carrington was an integral part of the women’s liberation movement in Mexico, and in the 70s, she contributed to a Mexican horror film.

Carrington would happily remain in Mexico City for the rest of her life, finding community amongst other expatriate artists, one of whom she married. Together with her husband, Hungarian photographer Emerico “Chiki” Weisz, Carrington had two children—Gabriel, who grew up to be a poet, and Pablo, who followed in his mother’s footsteps to become a Surrealist painter.

Later Life And Legacy of Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington’s trailblazing tenure as a Surrealist painter spanned eight decades and two continents. In 2005, one of Carrington’s works was sold by Christie’s for $713,000—setting the record for the highest price paid at auction for a living Surrealist painter. Despite this, many discussions of modern and contemporary art in the Western world frequently neglect to mention Carrington’s enormous influence on the trajectory of Surrealism in Europe and Mexico and in the global fight for women’s equality. Towards the end of her life, Leonora Carrington remarked, “The only thing I know, is that I don’t know”—illustrating how her creative exploration, both within her mind and throughout her surroundings, was a lifelong and constantly evolving pursuit.

Even after her death, Carrington’s work and ideas continue to resonate and expand their reach. She has been the subject of retrospectives at major museums. In 2018, thanks to donations from Carrington’s son Pablo Weisz Carrington, the Museo Leonora Carrington opened two venues in Mexico, where a collection of the Surrealist artist’s art and personal belongings can be enjoyed. Most recently, in 2021, a newly-discovered set of tarot illustrations by Leonora Carrington was published in a book, enchanting new audiences with its otherworldly illustrations in an iconic format.