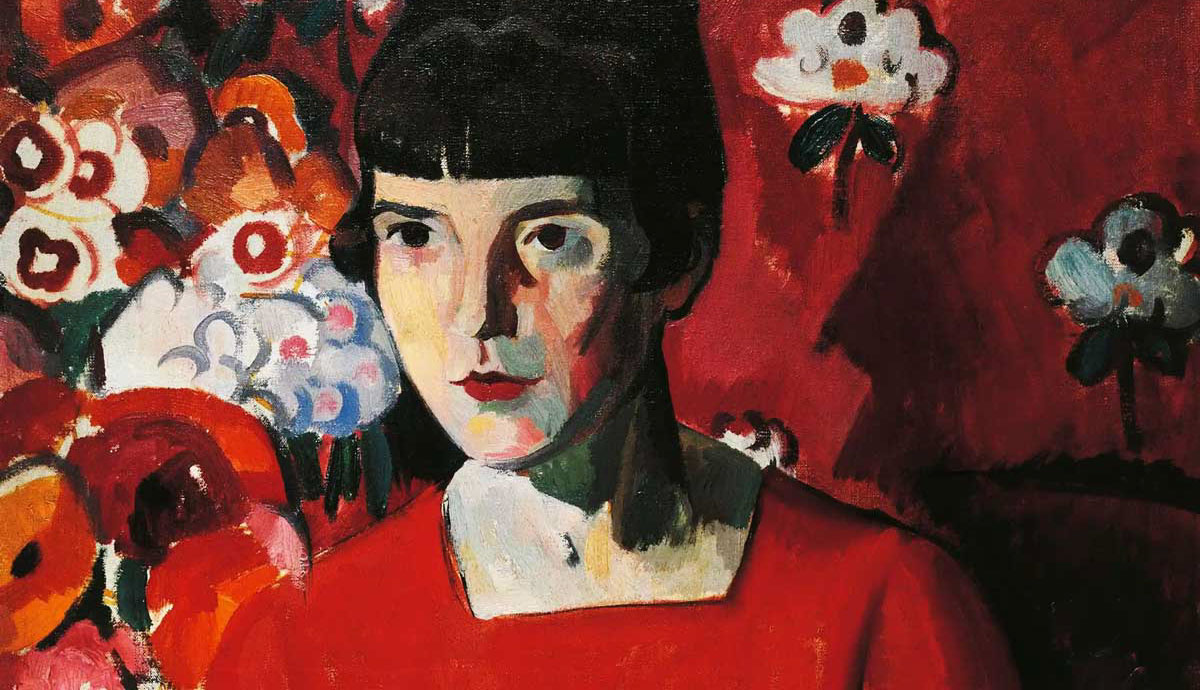

Katherine Mansfield was a New Zealander by birth who moved to London and established herself within the city’s literary scene by writing vivid, impressionistic short stories. Though hers was a relatively short life, she lived it to the full, traveling around Europe and taking many lovers, including Maata Mahupuku. When she died at age 34 of tuberculosis, her husband John Middleton Murry was keen to establish her reputation as a genius and something of a saint. While she may not have always been saintlike, many of her best short stories can indeed be seen as works of genius, and she is widely considered one of the most significant writers of English modernism.

Katherine Mansfield: Early Life

Born Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp in Wellington, New Zealand on October 14, 1888, Katherine Mansfield was the third child of Annie Burnell Beauchamp (née Dyer) and Harold Beauchamp, a wealthy banker and businessman who would go on to become the chairman of the Bank of New Zealand. Hers was a privileged childhood, though her parents were somewhat emotionally distant (and often abroad traveling for long periods of time). She was largely brought up, alongside her three sisters and brother, by her beloved grandmother.

Mansfield was educated at Wellington Girls’ College and Fitzherbert Terrace School before moving to London in 1903 with her two older sisters to board and study at Queen’s College. Here, the young Mansfield was free to pursue her own academic interests, taking classes in English, French, German, singing, and cello (at the time, she harbored ambitions for a musical career). It was also at Queen’s that she first met Ida Baker, with whom Mansfield remained friends for the rest of her life. Much to her disappointment, the Beauchamp girls were brought back to Wellington in 1906 when their parents had decided that they had finished their education.

Nonetheless, she did befriend (and become infatuated with) the local artist Edith Bendhall. Katherine also began to enjoy success as an author in her own right, publishing multiple stories in the Australian literary monthly magazine, the Native Companion. These were her first paid publications and marked the beginning of her career as a professional writer, having now abandoned her musical aspirations.

London Life: Writing, Love Affairs, & Marriage

Despite having made something of a success of her time in New Zealand, Mansfield remained eager to return to London. On the strength of her burgeoning career as a writer, her parents allowed her to settle there in 1908, providing her with an annual allowance of £100.

Here, she took up residence at Beauchamp lodge and was soon reunited with the musical Trowell family, whom she had known in Wellington. She soon fell in love with Garnet Trowell, the family’s younger son, with whom she began an affair. During their affair, however, Mansfield’s relationship with the Trowell family began to deteriorate. And when she revealed the romantic nature of her relationship with Garnet, the Trowells forbade the relationship to continue, expelled her from the house, and refused to have anything more to do with her.

By this time, however, Mansfield was pregnant with Garnet’s child. According to Claire Tomalin, it is for this reason that she then set about seducing George Bowden, a Cambridge-educated singing instructor in his early thirties. The two were married on March 2nd, 1909 at Paddington Registry Office. Back at their honeymoon hotel suite, however, Katherine refused to consummate the marriage and left that same night without informing George. A few days later, she traveled to Glasgow, where Garnet was performing as part of an orchestra and was reunited with her lover.

After following Garnet around as his orchestra toured for a while, she returned to London. Meanwhile, her mother had decided to pay her a visit at the end of May. It was Katherine’s mother who arranged for her daughter to stay in Bavaria for a while, presumably to hide her pregnancy from their acquaintances. On her return to New Zealand, Katherine’s mother cut her out of her will.

A Visit to Bavaria

Her mother’s decision to cut her out of her will, however, was unknown to Katherine, who at the time was staying in the Hotel Kreuzer in Bavaria, before moving to the Pension Müller. This was to provide the inspiration for her first collection of short stories, In a German Pension, published in 1911.

Her trip to Bavaria was also a sad one, however. She suffered a miscarriage after trying to lift a heavy suitcase. Without a husband on the scene, this caused something of a scandal in the Pension Müller. Ida, therefore, quickly arranged for Katherine to move in with Fräulein Rosa Nitsch, who ran the lending library in the local village.

It was here that she met Floryan Sobieniowski, a Polish writer and translator. The two began a relationship and planned a future together of intellectual discussion and literary labor. Their relationship soured, however, after Sobieniowski gave Mansfield gonorrhea. Mansfield then turned to Ida for help, who sent her money for the fare to return to London, met her on her arrival, and put her up in the Strand Palace Hotel in December. Instead of meeting Floryan in Paris as they had discussed, she cut ties with him and remained in London.

Now back in London, she resumed contact with Bowden. Though they never consummated the relationship, she moved in with him in his Gloucester Place flat. She shared some of the short stories she had written while in Bavaria with him. Recognizing her talent, Bowden suggested that she should submit them to A.R. Orage’s New Age magazine. She went on to be a regular contributor to New Age, and Orage went on to substantially influence her writing.

Meeting John Middleton Murry and the Lawrences

It was another literary editor who was to have a seismic impact on her personal life, however. John Middleton Murry was the editor of Rhythm magazine and had recently published an article in the New Age. A fellow New Age contributor, Willy George, had submitted one of Mansfield’s stories for her to Rhythm, though Murry turned this down and asked instead for something darker.

Mansfield duly sent him her murderous short story, “The Woman at the Store.” Murry was so taken with this story that he insisted that George arrange an in-person meeting between him and Mansfield, which took place in December 1911. Soon afterward, Murry invited her to write reviews for Rhythm, and she invited Murry to become her lodger before taking him as her lover. Though she left him twice (once in 1911 and again in 1913), they largely stayed together until her death in 1923, marrying in 1918 once her divorce from Bowden was finalized. Needless to say, however, their relationship was not always happy.

It was through Rhythm that Murry and Mansfield were brought into contact with D.H. Lawrence. In 1912, Mansfield invited Lawrence to contribute to the magazine. This marked the beginning of an important relationship between Mansfield, Murry, Lawrence, and Lawrence’s partner, Frieda.

Both Mansfield and Murry attended Lawrence and Frieda’s wedding in 1914, with Murry acting as one of the official witnesses, and the two couples also spent time together in Cornwall during the First World War. Lawrence also dedicated The Rainbow to Mansfield and Murry and immortalized them as Gerald and Gudrun in Women in Love, though they were not best pleased with these literary tributes. It is also now generally thought that it was Lawrence from whom Katherine contracted the pulmonary tuberculosis that was to kill her.

Friendship with Virginia Woolf

There was another prominent modernist writer with whom Katherine was friends, however. Once, while staying at Garsington, Ottoline Morrell lent Mansfield a copy of Virginia Woolf’s debut novel, The Voyage Out, and fellow Bloomsbury Group member Lytton Strachey passed on her compliments to the author. When Leonard and Virginia established the Hogarth Press in 1917, Virginia approached Mansfield with an offer to print some of her work. Mansfield reworked her short story “The Aloe,” which was renamed “Prelude” and published by the Hogarth Press. Not long after this, Katherine was invited to dine at Richmond and stay for a long weekend at Asheham, two of the Woolfs’ homes.

Their friendship was thus begun in mutual admiration for each other’s work. Katherine was often too ill to maintain contact and occasionally expressed her jealousy of Virginia’s domestic comforts in contrast with her own. Mansfield also wrote a somewhat scathing review of Woolf’s second novel, Night and Day, in the Athenaeum, of which Murry was made the editor in 1919. Though Woolf was wounded by her friend’s criticism, she was still eager to see her after this whenever she heard Mansfield was in London.

It typically fell to Virginia to do the chasing, “being” (by her own estimation) “the simpler, more direct of the two,” sending her letters, cigarettes, and flowers (see Further Reading, Tomalin, p. 199). But Virginia felt she could talk of writing with Katherine as she could with no one else, save perhaps for Leonard. And Katherine, in turn, did pay her a visit after her marriage to Murry, during which Virginia noticed with concern how ill she looked. Virginia recommended a Dr. Stonham to her, who examined Katherine and informed her that both her lungs were tubercular.

Katherine Mansfield’s Final Years

Mansfield spent the last few years of her life in a frantic search for a cure, and in equally frenetic bursts of literary energy. Having been warned not to winter in London, she made frequent trips to the continent (which meant she and Murry were often apart) and published two further short story collections between 1920 and 1922. She stayed in Switzerland from May 1921 to January 1922 in the hopes of trialing Henri Spahlinge’s tuberculosis treatment and writing some of her best short stories, including “At the Bay” and “The Garden Party.”

From Switzerland, she moved onto Paris in February 1922, where she undertook a round of X-Ray treatment. She again sojourned in Switzerland, where she wrote her will, before returning to France, this time staying at George Ivanovich Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in Fontainebleau, where her room was so cold that she slept in a fur coat. It was also at Gurdjieff’s suggestion that she would sit on a raised platform above the Institute’s cowshed, which he argued was a traditional cure for tuberculosis.

During her stay at Gurdjieff’s Institute, Murry had been working in London, but he came to stay with her on January 9th, 1923. That night, Mansfield began climbing the stairs to her room, which induced a coughing fit. The cough worsened, bringing on a major hemorrhage. She died that night at just thirty-four years old.

Though she had a rather equivocal attitude towards the women’s suffrage movement when she arrived in London in 1908, Katherine Mansfield was very much one of the early twentieth century’s “New Women.” She lived life on her terms – and paid heavily for her misadventures. While some critics have attempted to dismiss her as a minor writer lacking the stamina necessary to write a novel (and thereby dismiss the short story as a minor literary form), Mansfield pioneered a new vision for English short fiction that was influenced by French and Russian writers, all the while suffering with a chronic illness and later with the tuberculosis that would kill her. But, as she herself boldly declared, she was “a writer first” and foremost.

Further Reading:

Harman, Claire, All Sorts of Lives: Katherine Mansfield and the Art of Risking Everything (London: Vintage, 2023).

Tomalin, Claire, Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life (London: Penguin, 2012).