The Civil War between the United States and the Confederacy was fought over the issue of enslavement. Slavery was the cornerstone of the Southern economy, and without it, the business and wealth of the region would decline steadily. After the Union won, the South reintegrated into the US. However, several factions of former Confederates could not accept this defeat, seen as defamation of their homeland. Soon after the end of the war, reasons for why the Confederacy was just in its endeavors began cropping up. This is now known as the Lost Cause philosophy.

Origins of the Lost Cause

In April of 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered in Appomattox, Virginia. The Confederacy had exhausted its resources, and the landscape of the American South was destroyed. They could no longer stand against the federally backed Union Army. In defeat, the Confederate States of America ceased to exist, and during Reconstruction, the southern states were integrated back into the United States.

In the ashes of the war, defeated Southerners, former enslavers, and those who saw the war as “unjust” against the South began building a new narrative, one that would glorify the Confederacy. Not only did it act as a salve to the wounded pride of former Confederates, but it also justified the power of white supremacy in the South in the years following Reconstruction.

The Lost Cause was born through many mythical avenues, but what certainly helped it succeed as a philosophy was the celebration of Memorial Days following the end of the Civil War. Families of Confederate veterans and those who had lost loved ones to the war laid wreaths and flags at the graves of Confederate soldiers, honoring those who had fought for the cause of the South.

This gave way to the heroization of Confederates. Eventually, groups were cropping up all over the South, mostly made up of these same family members who were in a desperate search to justify the deaths and disfigurations suffered by their husbands, brothers, sons, and fathers during the Civil War. The Lost Cause was born of this idealization and memorialization of the Antebellum South.

It has been referred to as “Confederate nostalgia” by many historians and is characterized by a quote from a former Confederate general, who claimed, “If we cannot justify the South in the act of Secession, we will go down in history solely as a brave, impulsive but rash people who attempted illegally to overthrow the Union for our Country.”

The Philosophy of the Lost Cause

The thesis of the Lost Cause was that the Confederacy was defeated for fighting for their freedoms and their states’ rights. The soldiers who fought for the South were defending their land against federal control, not for the right to enslave others.

The main tenets of the Lost Cause philosophy followed the idea that the South was victimized by the tyranny of the federal government. The Civil War was not fought over slavery but over the issue of Constitutional states’ rights. The Lost Cause posited that secession was based upon the North and, thereby, the federal government, trying to encroach on the tradition, culture, and economy of the Antebellum South.

Following this thread of thinking, the Confederate States of America’s secession was simply a natural progression of the American Revolution. The South wanted to be free of a governing overlord, which was aligned, in their view, with the Constitution and its outline of state versus federal power.

The Lost Cause treated slavery as a minor issue in the conflict because slavery was not a cruel institution but rather one that protected and benefited African Americans. The lives of Black Americans were significantly better, according to the Lost Cause, when they were in the institution of chattel slavery, and that way of life should be maintained.

This helped to bolster the overthrowing of Reconstruction-era governments and fought against the passing of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Black freedmen and women were not prepared for freedom, touted proponents of the Lost Cause, so white government was the natural option.

The Lost Cause also sought to justify why the South had emerged from the Civil War in defeat. This was explained away as a matter of resources and men. While the North was the hub of industry and manufacturing, the South mainly depended on agriculture to sustain its economy and wartime resources. The Union overwhelmed the Confederates’ ability to fight with the “meager” supplies and soldiers they had. Many Confederates stated that had it not been for this, the South would have won the war.

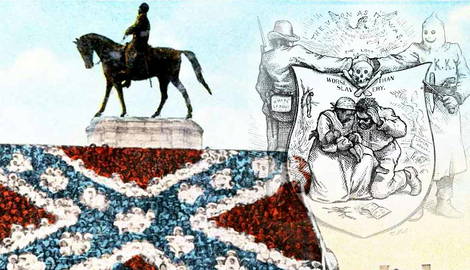

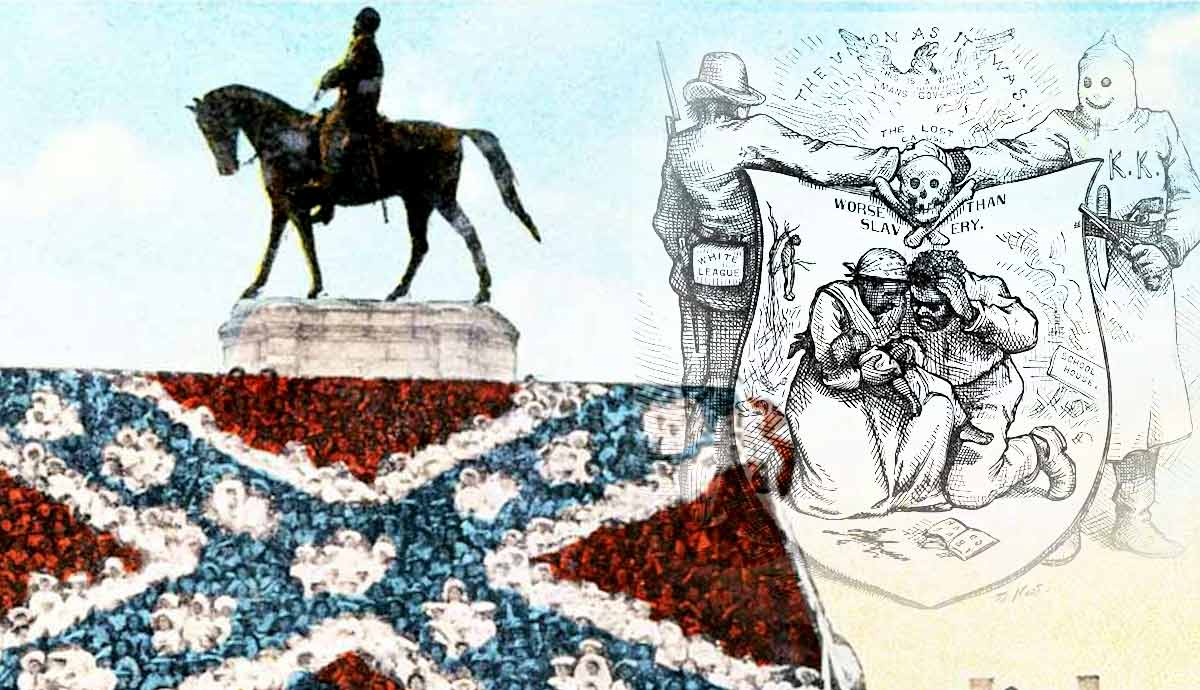

Thus, the soldiers of the Confederacy, both dead and alive, were treated as heroes and were canonized in the cult of the Lost Cause. Confederates retained their honor, even in surrender, and were compared to Biblical saints for their bravery in battle. None was so revered, however, as General Robert E. Lee. He was the ultimate Christian soldier who took up arms against his own family to defend his state of Virginia. This “Cult of Lee” was and still is revered in the several hundred statues and memorials of the Confederate General.

Lee’s close second as most holy was Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, a Confederate general, who died in the Battle of Chancellorsville (under mistaken friendly fire). He was the martyr of the Confederate cause, who died for the South and its ideals.

The Lost Cause philosophy also had several practices and tenets that helped its revisionist view become mainstream in the South. The Civil War became the “War Between States,” or the “War of Northern Aggression,” and the textbooks in schools reflected the philosophy. Memorials went up throughout the South, and as early as the late 1860s to early 1870s, the Lost Cause began spreading and pervading the ruins of the Old South.

Myths of the Lost Cause

The Lost Cause philosophy was perpetuated through a series of myths, all of which were used to justify the cause of the Confederacy and some of which were used to justify its destruction in the Civil War. These myths were spread through several mediums: monuments, school curricula, literature, historical landmarks, and cemeteries, to name a few.

1. States’ Rights

The Lost Cause philosophy was perpetuated through a series of myths, all of which were used to justify the cause of the Confederacy and some of which were used to justify its destruction in the Civil War. These myths were spread through several mediums: monuments, school curricula, literature, historical landmarks, and cemeteries, to name a few.

The most widely promoted myth of the Lost Cause philosophy was that the Civil War was not fought over slavery but rather over states’ rights. This myth was promoted almost immediately after the surrender and dissolution of the Confederacy as a way to soften the position of the South. However, the historical record of Southern secession disagreed with the Lost Cause. According to the Vice President of the Confederacy, Alexander H. Stephens, in 1861, “[the Confederacy’s] foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” Similarly, the Mississippi secession declaration stated that “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery.”

The institution of slavery was a clear motivator for the Confederacy to secede from the United States; even still, the Lost Cause attempted to revise history and push the myth that the Southern states simply wanted to maintain their rights to govern themselves, which, of course, included the right to enslave others.

2. The Confederacy Lost due to Superior Union Resources

Another myth that was and is widely promoted within the Lost Cause is that the South lost the war simply due to its lack of resources compared to the United States. In her primer Catechism for Southern Children, Mrs. J.P. Allison asked, “If our cause was right why did we not succeed in gaining our independence?” to which children would, ideally, respond, “The North overpowered us at last, with larger numbers.” While the South faced great destruction by the Union and was overpowered in the end, other factors were at play in the surrender of the Confederacy.

For instance, the Confederate military experienced a great divide among social and economic classes, as well as failing spirits among its troops. Desertion increased as the war went on, and the losses kept coming. In addition to this, with the emancipation of enslaved people, the South was losing the free labor that propped up its wartime industry. The Lost Cause denies any hint that the South was internally hemorrhaging with problems and instead chooses to blame the Union.

3. Slavery Was a Happy Institution

A sinister tale was also twisted surrounding slavery and its enforcement in the South. While chattel slavery was a brutal institution, no matter if those enslaved were treated “well” or not, the Lost Cause Philosophy promoted slavery as an institution that benefited the enslaved.

Lost Cause textbooks, literature, and caricatures of African Americans promoted a romanticized view of enslavement, spinning apocryphal tales of slaves who sang in the fields as they picked cotton and loved their masters fiercely. They were happy on plantations, where many promoters of the Lost Cause believed they felt safe and cared for under white planters.

This delusion was part of a grander scheme of the Lost Cause, which was to promote the South, with its sprawling plantations and genteel culture, as a romantic and idyllic setting that was lost as a result of the evils of the Union. The Southern Gentleman was the ideal of manhood, and the Southern Belle that of womanhood.

The South itself became a character in the Lost Cause mythology, with its rolling hills, live oak trees dripping with Spanish moss, and its great plantation houses with tall white columns. The Lost Cause venerated the Antebellum South as an ideal to return to, which, of course, included the idea that Black Americans would once again be subjugated to enslavement. In short, the Lost Cause romanticized white supremacy and gave validity to it through its obsessive nostalgia with the Antebellum South.

These myths paved the way for the Lost Cause to infiltrate politics, education, and the culture of the South. They started the trend toward systemic racism, resulting in the end of Reconstruction, the establishment of Jim Crow, and mainstream acceptance of white supremacy.

Lost Cause Groups

Several groups promoted the Lost Cause Philosophy throughout the years, beginning quickly after the end of the Civil War. Memorial groups started cropping up throughout the South, but two central groups remain integral to the Lost Cause Philosophy: the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV).

Both the UDC and the SCV are still active organizations today. Since their inception in 1894 and 1896, respectively, they have promoted the memorialization of the Confederacy and pushed for recognition of the Lost Cause Philosophy.

Both are hereditary organizations that revolve around promoting the aforementioned myths in several ways. The most notable and well-known by the American public are the monuments of Confederate war heroes that still dot cities and towns nationwide. These monuments are visual reminders of the Lost Cause and were placed intentionally to promote the philosophy and its revisionist history.

The UDC and the SCV both pushed to have educational curricula reflect the Lost Cause philosophy and venerated the Confederacy in Southern schools. They hosted writing contests on the Confederacy for high schoolers, maintained Confederate war artifacts in libraries, and hung portraits of Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson in school hallways.

The Lost Cause philosophy also inspired celebrations within the UDC and the SCV. They began the celebration of Confederate Memorial Day, usually observed in cemeteries or memorial sites founded or constructed by the UDC and SCV. During such celebrations, impassioned speeches are given about the sacrifice and gallant legacy of the Confederate troops, while Confederate battle flags and wreaths are placed on gravestones.

The groups also actively supported the Ku Klux Klan, especially during its second iteration. The UDC notably promoted the KKK to a mythical status of the armies of God, saving the romanticized South from the scourge of equality. The SCV also promoted the terrorism of the KKK, and both groups campaigned to include Klan propaganda in schools throughout the South.

Several powerful people were involved in groups that promoted the Lost Cause. President Harry S. Truman, Clint Eastwood, and Senator Strom Thurmond were all members of the SCV, while several notable writers, politicians, artists, and journalists served as members of the UDC. Both organizations still exist today and actively promote the myth of the Lost Cause.

The Lost Cause Today

It should come as no surprise that, although it is not often explicitly named, the Lost Cause is still prominent in the discussion surrounding systemic racism in the United States. Groups like the UDC and the SCV are still active and defend the use of the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of “heritage, not hate,” and their monuments to the Confederacy still stand in many town squares and parks throughout the country.

Renewed interest in the topic of memorializing the Confederacy arose in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter Movement that followed. The Lost Cause is central to those who defend the monuments and flags of the Confederacy, as it has been for nearly 160 years since the end of the Civil War. The far-right movements of the contemporary United States have integrated the Lost Cause with their focus on states’ rights, heteronormative gender roles, and systemic racial oppression.

Recently, ideas of the Lost Cause have also been linked to the book bans and revised curriculums that have seemingly swept over the American South. Eliminating mentions of slavery as a cruel institution from lessons and banning books that examine the Confederacy in a negative light is still a matter of contention actively occurring in the United States, with proponents of the Lost Cause in the far-right movement allowing revisionist history to thrive.

The Lost Cause philosophy began as a harmful rhetoric that idealized the Confederacy and the Antebellum South and continues to perpetuate racist and regressive tropes in the United States today. The mythos still enraptures its followers and pushes them to accept a version of history that is reductive and harmful to those who were and are oppressed in American society and inspires hate and division in an increasingly polarized nation. While it may never fully go away, protests against monuments and ideals of the Lost Cause are ongoing, allowing hope that the revisionist philosophy will one day be a true relic of the past.