When we think of the lost wax process, the images that perhaps come to mind are Ancient Greek bronze sculptures or the works of 19th-century French artist Auguste Rodin. However, its origin and use are not bound to a single culture, region, and time period but instead traverses all three, acting as a common thread between people across cultures and spaces. Evidence for lost wax technology is prevalent as far back as 4000 BCE and continues to be used in contemporary art and commercial production.

The Lost Wax Process: An Art Form of Absence

At its most basic, the technology of the lost wax process involves first the creation of an object in wax, which is then covered in clay, plaster, or another material that is able to withstand high levels of heat. In her book Male Nudity in the Greek Iron Age: Representation and Ritual Context in Aegean Societies, Sarah C. Murray states that typically, beeswax was used but required filtration due to the build-up of natural materials such as dirt or dead bees. It would also sometimes be mixed with tallow, which is sheep and or cow fat, or turpentine, which is diluted tree resin, usually from the pine tree family.

The plaster cast or inflammable outer layer, otherwise known as an investment mold, is usually applied directly to the wax sculpture or object on a flat surface, which creates a hole at the base where the wax will flow out from when heated. According to Murray, in the ancient Aegean area comprising modern-day Greece, north Turkey, Crete, Rhodes, Carpathos, and Kasos, the investment mold could have been made from a combination of charcoal, ash, and manure, materials still utilized in contemporary foundries. In some cases, additional strips of wax are made to form rods that are attached to parts of the object that won’t affect the final design. These act as tunnels that will guide the liquified metal into the mold.

This mold, once dried, is typically inverted upside down and heated so the interior wax melts out of the hole, leaving an empty mold that has taken on the shape and details of the wax object. It is through this step that the term lost wax is derived, as the wax disappears or becomes “lost” in the process of heating. Left upside down, the exterior plaster shell is then filled with a metal, or several types of metal, that has been heated to liquid form and poured into the cast. Once the liquid metal is dried, the plaster shell is broken away to reveal the metallic form of the original wax object. A famous example of this method would be Donatello’s David, which is located at the Museo Nazionale Del Bargello in Florence.

In the chapter Lost-Wax Casting from the book Finding Lost Wax: The Disappearance and Recovery of an Ancient Casting Technique and the Experiments of Medardo Rosso, Francesca G. Bewer describes this process as an art form of alternating positive and negative spaces; perhaps it could even be argued that this method was a precursor to printmaking in the way that it utilizes positive and negative space.

Variations of the Lost Wax Process

The technique described above refers to the direct process of lost wax, but there is an indirect method of lost wax casting, otherwise known as hollow casting. With this method, instead of an entire model made of wax, a thin layer of wax is applied to an interior core. In doing so, the heated metal will only take shape over the center instead of completely filling the inside of the mold. This is a method that is most commonly used with larger objects, which, due to their size, have a higher probability of uncontrollable variations and are extremely heavy and costly.

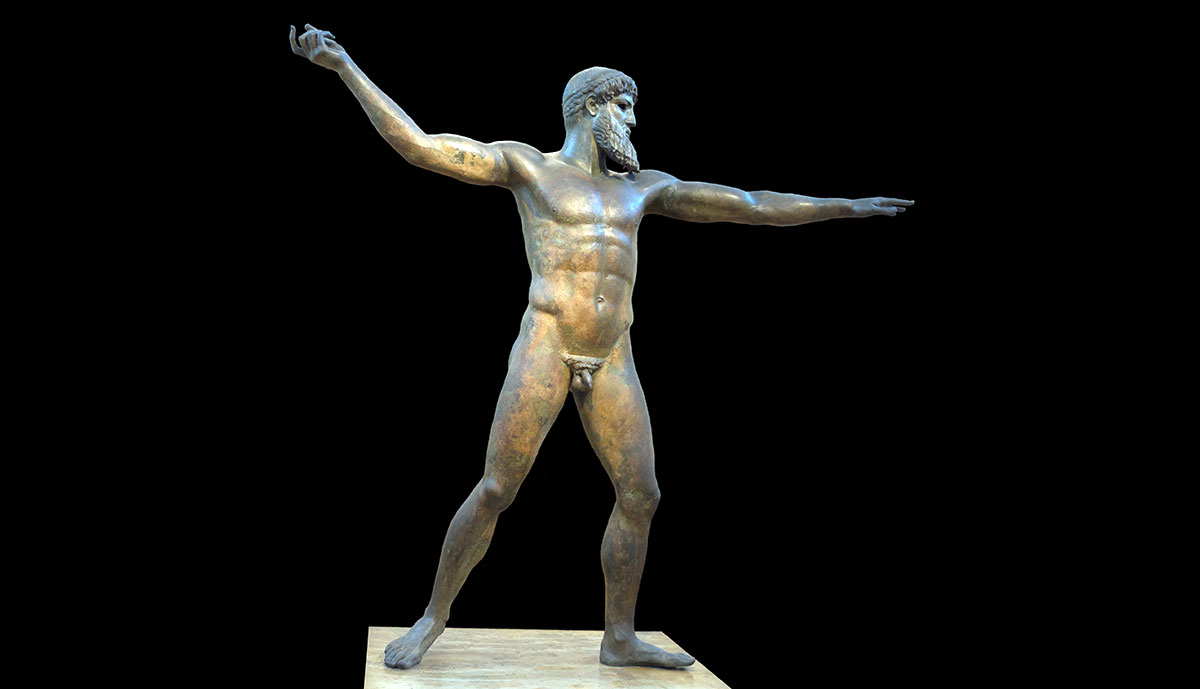

Bewer mentions that the hollow method was typically used for bronze for these reasons. Unlike the direct method, which melts the original model in the process of firing, the indirect method creates a model that can be reused, resulting in the possibility of creating multiple productions of the same object. The material used to create the core was traditionally made with layered plaster, but contemporary techniques could use gelatin or rubber. An example of a work using the indirect method is the Bronze Statue of Poseidon or Zeus, which was found in the 1920s at the site of a second-century BCE shipwreck off the coast of Cape Artemision.

According to Kosmas A. Dafas, a specialist in Ancient Greek bronze statues, some sculptures from the Classical period in Ancient Greece may have actually been constructed with a dual direct and indirect process: the bodies would be constructed using the indirect or hollow method while the head and garments would be made using the direct method. Dafas also mentions that it was actually the introduction of bronze and its absorption into Ancient Greek art production that generated the possibility to create sculptures with more movement, a divergence from the static nature of marble sculptures in the pre-Classical period.

The material of bronze transformed the way that limbs could be executed. They became extended outward from the body, breathing life into the sculptural art form. However, Murray mentions that bronze could actually be referring to a mix of copper, lead, tin, and zinc: “many so-called bronze sculptures are, in fact, technically made of ‘brass’—a copper alloy whose second greatest component is zinc.” In the 19th century, technological developments transformed the way this process was carried out, involving gelatin, rubber, and other synthetic materials. A method of lost wax casting used today is referred to as investment casting, which is used in the commercial production of metallic parts. Furthermore, the lost wax process additionally laid the foundation for modern dentistry and continues to be used for jewelry production.

The Universality of the Lost Wax Process

What is most compelling about this method of art and object-making is that it has been utilized across cultures and regions for almost six thousand years. Further, the appearance of this process has become a marker of technologically advanced civilizations due to the complexity of this technique. There are variations in the types of wax, molds, and metals utilized that are idiosyncratic based on regional differences and the natural materials available, but the overall process remains parallel cross-culturally.

Murray states that the direct method, the one that results in a solid form of metal, of the lost wax process was known by the 2nd millennium BCE (2000-1000 BCE) in the regions of the Levant and Mesopotamia, comprising the west Asian regions of modern-day Kuwait, Syria, Turkey, Iran, Lebanon, Palestine, Cyprus, Jordan, and Israel. However, archaeological evidence points to the use of this technique almost two thousand years earlier in the late Chalcolithic period. This is used to refer to the period of time between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age that is hypothesized to begin around the 5th millennium (4500 to 3800 BCE). In the article Identification of Fazael 2 (4000–3900 BCE) as First Lost Wax Casting Workshop in the Chalcolithic Southern Levant, excavations from the region of Fazael in the Jordan Valley provide evidence that Fazael could be the earliest lost-cast waxing site ever identified.

The Nahal Mishmar Hoard is a group of over three hundred objects that were made using the lost wax method found by the Nahal Mishmar river outside of modern Jerusalem that could be tied to a production site in Fazael. These objects are particularly interesting, the authors state, because they were created using a technology that became lost, as evidence for it diminishes after this period. However, specialists are at least able to identify that the lost wax process was used due to studies on object molds found at this site: “mould remains revealed a multi-layered mould design with pastes prepared from different clays, carbonaceous sand and vegetal material, or plaster mixed with animal dung and basalt split.”

The region of Bulgaria and southern Romania is also home to the earliest evidence of the lost wax process through grave objects discovered at the Varna I cemetery. These objects show a highly advanced understanding of metalworking, and although they are dated to the Middle to Late Chalcolithic period, the authors of the article On the Invention of Gold Metallurgy: The Gold Objects from the Varna I Cemetery (Bulgaria)—Technological Consequence and Inventive Creativity state that the level of understanding points to a long-standing tradition and practice of the lost wax method that could go back even further.

Other examples of this technology in Asia are along the Indus River Valley. In the article The Lost-Wax Casting of Icons, Utensils, Bells, and Other Items in South India, the authors state that this method had been known by people residing in the region of South Asia since the 2nd (2000 BC to 1001 BC) to 3rd (3000 to 2001 BC) millennium. Evidence for this can be found in the sculptures of the Mohenjo-Daro Girl and Mother Goddess of Adichanallur that date to the 3rd millennium.

Lost Wax in Asia

In South Asia, this process gained cultural importance in the Hindu religion as a way to produce idols, so much so that Sanskrit texts such as the Śilpa Śāstra outlined materials used, their ratios, and how to execute idols in a step-by-step process. Artisans would utilize wax made from powdered tree resin, beeswax, and ground nut oil, which were processed through a series of heating and straining. They would create a wax model of an icon, the most important step, then conceal the model through several layers of alluvial or muddy soil, the outer husks of rice, and cow manure to create a mold.

Once completed, it would be placed in an open-ground oven. Upon heating the mold, while still hot, it would be placed into the ground and filled through a funnel at the top with panchaloha, or five metals, which were copper, gold, silver, lead, and zinc. The final act of removing the inner metal icon from the mold accumulated spiritual meaning: “The breaking of the mold to remove the icon is of great significance to the craftsman, since it is not merely an object but a transcendental entity.”

In the book Hindu Gods in an American Landscape: Changing Perceptions of Indian Sacred Images in the Global Age, E. Allen Richardson points out the cultural significance of lost wax idols in Hinduism: “Mūrtis [sculptures of deities] were understood as living presence. Cast in traditional methods using precise lost wax techniques, bronze anthropomorphic images became vessels for the deities who resided in them.” In addition to being a method to create objects for everyday life, the lost wax process became a method for people to connect with the gods they worship.

In other parts of Asia, towards the east, the lost wax process was used to produce bangles, drums, and other objects. Peng Peng, in A Study on the Origin of Chinese Lost-Wax Casting from the Perspectives of Art, Technology, and Social Agency, explores whether the lost wax process in China developed independently or was introduced from the modern regions of Thailand and Vietnam. This is due to sets of bangles and other objects that have been found at the sites of Ban Na Di (1200 BCE to 200 CE approximately) and Go Mun (1000 to 500 BCE) in Thailand and Vietnam, respectively, that point to being cast using the lost wax method. Peng explores the hypothesis that the technology was introduced into China from the northern steppes around the Anyang period, which started around 1200 BCE. However, Peng concludes the article by stating some methods were both introduced by external groups and developed within the region.

Lost Wax Process in Central America

Across the Atlantic in the regions of Central America, the lost wax process was used to create gold jewelry and other objects that could have been used as offerings or tribute. In the article Ceramic Molds for Mixtec Gold: a New Lost-Wax Casting Technique from Prehispanic Mexico, Marc N. Levine states the first evidence for the lost wax process in Mesoamerica dates from 650 to 700 CE, but that it wasn’t fully immersed in object production until around 1200 CE Within his study of lost wax ceramic molds at Tututepec, the capital of Late Postclassic (1100–1522 CE) Oaxaca in southern Mexico, Levine strongly suggests that instead of being filled completely with wax and then metal, these molds may have actually been used to make internal clay cores, implying the use of the indirect or hollow casting method.

The ceramic molds, which were in the shape of various animals or human heads, would be filled with clay and charcoal, removed and then covered in a thin layer of wax, then covered again in more layers of charcoal and clay paste until they were heated, the wax drained out, liquified metal poured in, and finally, the outer shell broken away to reveal the hollowed object. Levine thinks that the molds were used mostly for gold objects but could have also been used for copper and silver. This process provides an explanation as to how objects in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were standardized or how they were able to make perfectly replicated copies of the same object.

Lost Wax Process in Africa

Back across the Atlantic in western Africa, the lost wax process was used as early as the 9th century CE and is connected with the site of Igbo-Ukwu, an area from the southeastern region of modern Nigeria. In the article African Lost-Wax Casting, Alice Apley states that artisans would use beeswax or other latex and work in both the direct and indirect methods of casting. Tin was native to Nigeria, but most of the sculptures and objects are made with metals that were introduced to the area through far-reaching and long-standing trade relationships.

Apley mentions that brass was a metal introduced by Arabs in the 10th century, and it circulated widely in the creation of metal objects. Arabia was connected with the regions of the Levant and the Indian Ocean, which utilized this technology for centuries. This begs the question, did they also bring the knowledge of the lost wax process with them? Another famous example of the use of this process is the Benin Bronzes, which are most famous today for being the center of repatriation debates.

In the article On the Invention of Gold Metallurgy: The Gold Objects from the Varna I Cemetery (Bulgaria)—Technological Consequence and Inventive Creativity, the authors state: “there is a strong correlation between demographic growth, emergence of larger cultural complexes, a growing social complexity or inequality and technological enhancement and intensification, particularly of copper metallurgy.” The prevalence of this object and art-making technology across time and cultures speaks to a larger question about the relationship of people to the environments that surround them and the urge to mold and bend this nature to create objects of significance. The lost wax process has a continuing legacy that will continue to adapt alongside people but never disappear completely.