In his book Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Friedrich Nietzsche outlines the ideal kind of “Übermensch,” or “Overman,” whom he urges everyone to aspire to be. He also argues that only a select few are actually capable of this. While he may have possibly believed himself to eventually approximate this ideal, there is someone else whom he should have more explicitly acknowledged having perhaps gotten even closer: his estranged love, Lou Salomé.

What is Nietzsche’s “Übermensch”?

Before we explore Nietzsche’s relationship with Lou Salomé, and what makes her an Über-Woman, I will first outline what this ideal kind of human is, and his complicated views on women. It should be immediately noted that Nietzsche’s Übermensch refers more to a way of life rather than a particular person, though he does draw upon examples, some of which are specific, others which refer to groups of people.

Nietzsche’s Übermensch is a free spirit who individually rises above to reach their full potential. This kind of person is mentally and spiritually powerful, which Nietzsche sees as more important than being physically or biologically powerful (as has all too often been erroneously associated with him throughout history). This person is mostly the master of their own self: we can note a desire to redefine humanity here.

Nietzsche believed that his historical time represented a particularly poignant moment to usher in a new, better type of human: one based on entirely new values. But it will not be easy: we must, essentially, go under to go over. If we want to cross over to the other side of a mountain, we must start at the bottom and climb our way to the top before descending back down again.

This is exactly what Zarathustra—the protagonist of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra—does, as he is an embodiment of this type of Übermensch. The story begins after he spends some time in solitude in a cave, contemplating this ideal way to live, and then traverses up and down a mountain to try to convey his wisdom to the rest of humanity, only to find that few are ready to heed his call.

Nietzsche’s Philosophy on Nihilism

In the continuation of the story outlined in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche, using Zarathustra as his messenger, argues that his time was one of entering a major crisis of values because, as he famously claimed, “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him!” (This quote is from The Gay Science, book three, 125, but he says this on several occasions).

Now, of course, he does not mean this literally, but rather he is referring to traditional Christian values in the West: the entire foundation has been destroyed, by us, which will first bring a reality devoid of values and meaning; in other words, nihilism. But we cannot continue to live that way, so we will need to completely reinvent values and meaning. But again, not all are entirely capable of this: only the Übermensch really knows how to do this.

Nietzsche’s Übermensch is a master of the self. This is a higher individual who has made their life a work of art, leading to the self-affirming and rejoicing “Yes!” to want to eternally repeat the same life with all its ups and downs (this is Nietzsche’s idea of eternal recurrence, which is also elaborated on in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, though the first mention of this appeared in his earlier book The Gay Science).

Life as a work of art is defined by Nietzsche as one which balances the Apollonian and Dionysian forces (referring to the Greek Gods Apollo and Dionysus) that are part of the human condition; the former represents moderation, calm, rationality, balance, and so on, while the latter represents the more impulsive, passionate, excessive side. In other words, the idea is not to repress these drives, but to channel and use them properly. We can also tie these two forces back to the metaphor of traversing a mountain, with Apollo representing the mountaintop, and the valleys representing Dionysus—both stages are necessary to literally traverse a mountain.

Nietzsche’s Overman: Zarathustra

This person has also overcome what Nietzsche sees as human weaknesses, which he traces to Christian teachings and traditions. Most concisely stated, Nietzsche’s Übermensch is an individual living truly authentically—an ideal shared as a fundamental pursuit by existentialist thinkers.

Zarathustra is a specific example of this kind of person. Zarathustra references the ancient Persian prophet Zoroaster (circa 628-551 BCE). As a prophet, Zoroaster claimed history to be linear and teleological, shaped by the conflict between good and evil, with the former eventually winning out. But Nietzsche also sees this kind of thinking as the source of the bad which came from Christianity; the similar idea of the moral drama that is unfolding according to God’s all-benevolent plan.

This is one of the main sticky points of Nietzsche’s philosophy that are hard to comprehend because it seems inconsistent: the idea that he sees this kind of overhuman force at work in the moment these values were entrenched, but then those values themselves eventually turned out to be bad. In other words, the prophet, an overman, laid out the values that would be embraced by the Christian worldview, but they would ultimately suppress how to actually be an overhuman by stressing values such as humility, kindness, and sympathy. But the time has come to eradicate these morals, which will temporarily lead to nihilism, and eventually lead to new, better ones (again, we can think of the journey of crossing a mountain).

There is a major problem Zarathustra encounters: not everyone wants to hear what he has to say, and he realizes that only a select few are able to embody this. Nietzsche only cites a few examples of Overmen, such as Jesus Christ and Napoleon, but my claim here is that Lou Salomé has the potential to be included in that category as well.

Nietzsche’s Views on Women

Nietzsche’s relationships and views on women were very complicated and inconsistent (not unlike his philosophy). Of course, he would not deny this, given he argued that part of the human condition is precisely to be complicated and inconsistent. But we can arguably classify him as early in his adult life being almost a feminist, and later in life a misogynist, a trajectory that is arguably very much connected to his biography, and especially, with Lou Salomé.

During his lifetime, the topic of female emancipation was alive and well, especially regarding education. The historian Jacob Burckhardt recorded that Nietzsche was initially in support of this. Some of his early work is unmistakably clear regarding how he feels about women. For example, in Human All Too Human (1878), he even categorizes women as higher than men (though later he would say the exact opposite). There are many such examples that need not all be listed here but suffice to say, he was certainly not always a misogynist. Moreover, there are many possible explanations for the anti-feminist shift he makes, but here it will be highlighted how strongly it connects to his relationship with Salomé.

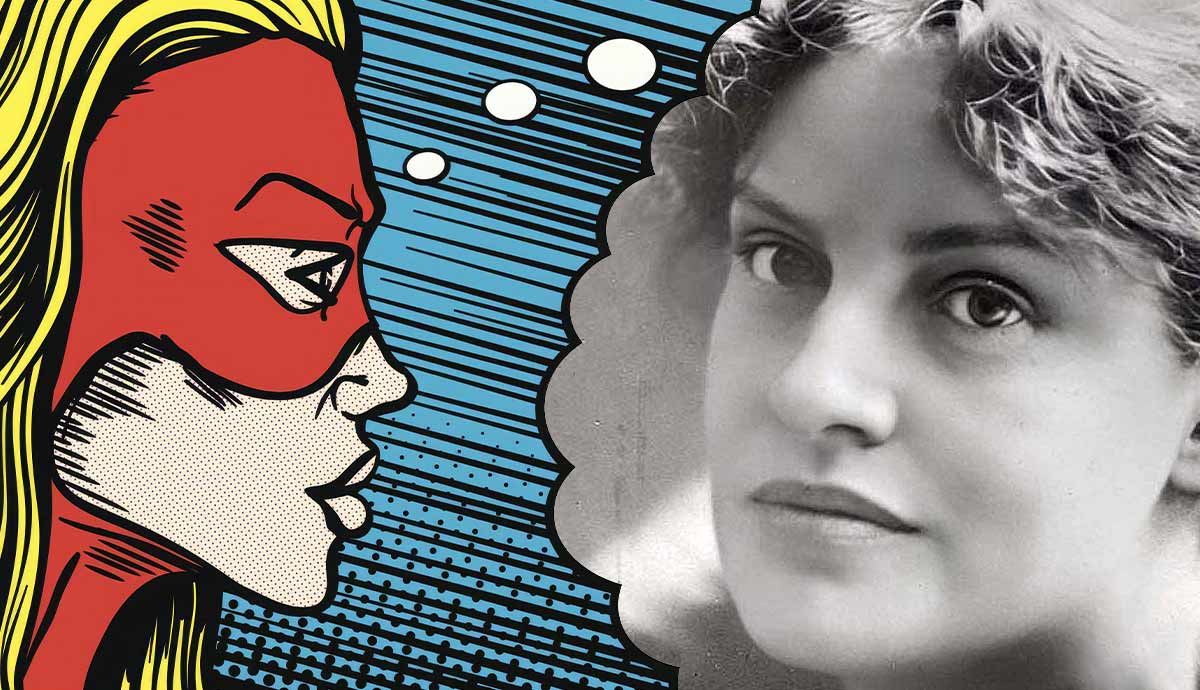

Salomé was a highly intelligent and beautiful Russian Jewish woman sixteen years younger than Nietzsche, but who immediately caught his eye (something that supposedly happened with most men she encountered). She went to the one university in Germany that permitted women to audit classes. During her studies, she came across Nietzsche’s work and aspired to meet him, which she eventually did through a mutual friend, Paul Rée.

But this would become a messy love triangle. Rée also ended up falling in love with her, and proposed before Nietzsche, but they were both rejected. Part of the reason was her desire to live her own life by her own standards; she fought against traditional expectations for women, such as becoming entrapped in a docile marriage. She did later fall in love with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, but the relationship was often defined on her own terms.

The Connections between Nietzsche’s Biography and Philosophy

There were other pivotal biographical events that certainly influenced Nietzsche’s philosophy, but the affair with Salomé was certainly very impactful. She came to embody his revulsion of women in general. It seemed he could never forgive her, which prevented him from embracing his own philosophy of amor fati, the love of the fate of life, since, as free spirits and overhumans, we must imagine it to eternally reoccur.

He described writing Thus Spoke Zarathustra as a great “bloodletting” to attempt to get over her, but he was not successful. She, on the other hand, perhaps seemed to him to have been at least more successful in pursuing the authentic and independent life she so desired. She, perhaps, embodied the overhuman more than Nietzsche was able to do, which he likely both resented and admired her for.

This all said, perhaps Nietzsche would be rolling around in his grave reading these theories. That would not be a rare event, as so much of his philosophy is and continues to be misunderstood and misused (such as, infamously, by the Nazis).

But perhaps he would admit to this interpretation of Salomé’s role in his life and philosophy. After all, as we witness with the character and story of Zarathustra, there are humans capable of personifying the overhuman, though it is just a select few. And certainly, at times, Nietzsche believed himself to be approximating that ideal as well. Further, Salomé was not the only important love interest in his life; scandalously, he also admired Richard Wagner’s wife Cosima Wagner (though Nietzsche eventually had an incorrigible falling out with the Wagners), whom we might also argue could exemplify a similar vision.

Either way, what is certainly an undeniable agreement among Nietzschean scholars is that Lou Salomé (among others, of course) had a profound impact on his life, and, resultantly, his philosophy, which is why we must consider these details if we are going to gain a better understanding of his life and work.