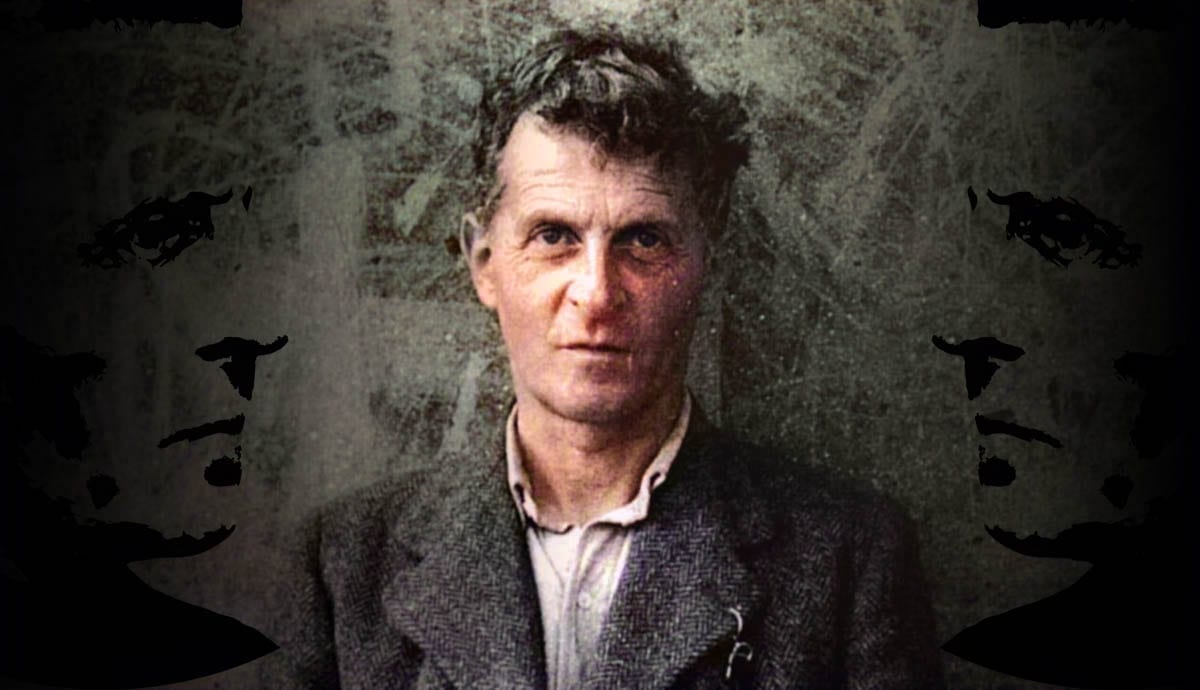

Ludwig Wittgenstein was one of the most influential and multi-faceted thinkers of the 20th century. The Viennese philosopher went through several career-changes, fought in the First World War, and radically changed his own philosophical perspective mid-way through his life. Most importantly, he believed he had finally solved all of philosophy’s problems, twice. This article tackles his personal life, the context he lived in, and the notorious transition from the Early to the Later Wittgenstein.

Ludwig Wittgenstein: An Ambivalent Philosopher

Ludwig Wittgenstein was born in 1889 into one of Europe’s richest families at the time, the youngest of nine children. Ludwig and his siblings were raised in the imposing Palais Wittgenstein in Vienna – the building does not exist anymore, though some pictures of both the exterior and the interior have survived. Their father, Karl Wittgenstein, was a titan of the steel-industry, set on leaving a legacy through his five sons; three of them would end up committing suicide. The patriarch was a renowned patron of the arts, which led to the household being filled with paintings, sculptures, and often even the artists themselves. One of Wittgenstein’s sisters, Margaret, was immortalized in a painting by Gustav Klimt. Ludwig, the philosopher, refused his share of the inheritance after his father’s death, and lived a humble (and sometimes harsh) life.

As a young man, Ludwig Wittgenstein was mainly interested in engineering and went on to pursue an education in aeronautics. His keen interest in the field led him to adopt an increasingly abstract approach, which provoked a lifelong passion for the philosophy of mathematics and logic. This new fascination culminated in his decision to contact Gottlob Frege, a logician and philosopher who had written on The Foundations of Arithmetic, a book that is now widely considered as the foundational text for logicism. Frege was impressed by the young philosopher and convinced him to study under Bertrand Russell, who would go on to become Wittgenstein’s mentor.

After being introduced into the world of philosophy, the young Wittgenstein worked incessantly on what would later become his first published book, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. His work was interrupted by the outbreak of WWI in 1914, for which he immediately enlisted. After four years of service, the philosopher was granted military leave, during which he stayed at the family home; this would prove to be an exceptionally unfortunate time for him. In the span of just a couple of months, his uncle, his brother, and his close friend and lover would die unexpectedly. In addition to that, the publishing house to which he had sent a copy of the Tractatus decided not to publish the book. A distraught Wittgenstein returned from his military leave, only to be captured by the Allies; he ended up spending nine months in a POW camp.

The Philosopher Who Didn’t Want To Be A Philosopher

These painful years proved to be critical. After the end of the war, a demoralized Ludwig Wittgenstein decided to give up on philosophy and pursue a simpler life as an elementary school teacher in a remote Austrian village. His attempts quickly failed: he was far too refined and eccentric to fit in with the small-town folks, and his eagerness for physical punishment was not well-received. After changing teaching posts several times, he finally gave up on teaching after a boy he had hit collapsed, an incident for which he was later tried in court. He would spend the next few years working on an architectural project ideated by his sister Margaret; the building, now known as Haus Wittgenstein, can still be seen and visited in Vienna.

Meanwhile, Bertrand Russell used his influence in the world of philosophy to ensure the publication of the Tractatus. The newly published book lead to the formation of the Vienna Circle, a group of academics that met to discuss the ideas and content of the Tractatus and who would go on to form their own philosophical movement, called logical positivism. Ludwig Wittgenstein often engaged in discussions with members of the Vienna Circle and developed a certain animosity towards some of them; he felt like his ideas were being misunderstood.

This “forced” reintroduction into the world of philosophy would prove to be effective, as Ludwig Wittgenstein eventually accepted a lectureship at Cambridge’s Trinity College in 1929. It was during this time that he worked on and developed the ideas of the “later Wittgenstein”, going against many of the principles he formerly expounded. After nearly two decades as a professor, Wittgenstein resigned to work on his own; he died in 1951. The philosopher never saw the publication of many of his most notorious works, including the extremely influential Philosophical Investigations, as he was never fully satisfied with his writings. Fortunately, many of his manuscripts were published posthumously, under the careful guidance of his pupils.

“Early” Wittgenstein: Language as a Picture of the World

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy has had such an interesting evolution that most academics view him as two philosophers in one; it is common to differentiate at least the “Early” from the “Late” Wittgenstein. The Early Wittgenstein is the philosopher who wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosphicus, the book which led to the forming of the Vienna Circle.

As the title reveals, the book is focused on logic. By the time Wittgenstein was writing the Tractatus, the topic of logic was becoming increasingly popular: Gottlob Frege had invented axiomatic predicate logic, which would become the basis of most later logical studies just a couple of decades earlier, and philosophers were catching on to the significance of his results.

Wittgenstein’s Tractatus aimed to demonstrate several things about logic, language, the world, and their relationship. It is important to note that logic was thought of as an abstraction of language, a way to look into its most basic and true structure. The fundamental aim of the book was to clear up what could be meaningfully said and thought.

Wittgenstein’s central idea was to view language and thought as isomorphic to reality; thought and language gain meaning by representing the world, just like a photograph represents its subject. For example, a model-plane represents an actual plane because they share some properties; they have the same number of seats, they are both white, the ratio between their length and width is the same, and so on. Wittgenstein believed that language is a model of reality because the two share a common logical structure. This approach was dubbed “the pictorial theory of language.”

The Meaning(lessness) of Philosophy

Through this basic idea, Wittgenstein aimed to draw a line between what could and what could not be meaningfully expressed. He was not interested in word-salad or other types of expressions we usually believe to be meaningless: he wanted to show that much of philosophy was actually meaningless and the result of linguistic confusion. For example, wondering about justice or what the meaning of life is cannot ever lead us to truth, because there could be no facts of these matters in the world that would answer such questions; and if there are no corresponding facts, there can be no meaning.

One of the principal tensions in the Tractatus is that it comprises of philosophical expressions which are supposedly nonsensical, according to the author. Wittgenstein even recognizes this fact. In one of the ending paragraphs of the book, the philosopher concluded that “He who understands me finally recognizes [my propositions] as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it).” This part of his work has been endlessly analyzed and provides notorious interpretative difficulties; how can reading the Tractatus be helpful if it consists of nonsense?

“Late” Wittgenstein: Language, Games and Language-Games

The transition from the Early to the Late Wittgenstein happened through the philosopher’s harsh critiques of his own work, especially when it came to its supposed “dogmatism.” Wittgenstein believed, soon after the publication of the Tractatus, that he was too concerned with just a sliver of language – namely with those expressions that could be true or false, such as “tomorrow is Monday” or “the sky is green” – and that he had ignored other meaningful, practical aspects of natural language. Regretful about his previous “mistakes,” he turned his attention to all the different ways in which language could be meaningful; the results of his studies are in the Philosophical Investigations.

The philosopher now suggested that meaning was the result of collective human activity, and could only be fully grasped in its practical context. Language is not only used to represent reality: it often serves radically different functions. For example, we do not seem to want to represent the world when we give orders, or when we count, or when we make a joke. This meant that the focus of his study would need to move from logic, which is the abstract form of language, to the analysis of ordinary language.

Throughout his analysis of ordinary language, Ludwig Wittgenstein stressed the analogy between linguistic practices and games. He noticed that language can take on different functions and that those different functions require us to adhere to different sets of rules. For example, the meaning of the word “water!” can differ radically based on the context and the function the expression serves in that context. We could be helping a foreigner learn its meaning; it could be an order; we could be describing a substance – the meaning changes with the situation in which the expression is uttered. What this means to Wittgenstein is that meaning is constituted through public, inter-subjective use, and not – as he previously thought – through its representation of the structure of the world.

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Take on the Role of Philosophy

Games and meaning share the fact that it is very hard to define them in a straight-forward and unique way. What do all games have in common? It is not a steady set of rules, as children’s play is free and fluid; it is not multiple players, as many games are solitary; it is not the possibility to “win,” as the rise of simulation games demonstrates. Just like it is impossible to define what a game is, so language and its meaning cannot be singularly defined; the best we can do is analyze different concrete linguistic practices.

All of this served one of the philosopher’s lifelong aims – to deflate and “clear up” philosophical problems. The Late Wittgenstein believed much of philosophy stemmed from the misinterpretation of words and their usage according to the rules of the “wrong” language-games. For example, when philosophers wonder about what knowledge is, they are taking a word that has its natural place in an organic language-game and warping its meaning; the meaning of knowledge can be grasped through the normal role of the expression in language.

The real objective of philosophy, then, should be to shed light on this type of confusion by focusing on the practical use of language, helping us avoid unnecessary puzzlement whenever possible.