Magic was a part of everyday life for the ancient Egyptians. They believed that dark powers were everywhere and that they could be combated through magic and rituals. Called heka, magic was a force involved in the creation of the world, and the gods and men contained heka in varying amounts. Similarly, Heka was the god of magic, the personification of magic itself. He is often overlooked among the vast lists of ancient Egyptian deities because he was so universal in his presence.

Magical Practitioners

To tame the dark forces at large, almost everyone “practiced” magic in some form. The lector priests were the most well-versed in magic. During religious ceremonies they would recite hymns and spells, both in official state rituals and at private funerals. The name lector translates into “the carrier of the book of ritual,” and the duty of the chief lector priest was to manage his temple’s collection of religious and magical documents. Later, the title of chief lector priest, written in Egyptian “ẖrj-ḥꜣb ḥrj-tp,” was shortened to “ḥrj-tp” or magician.

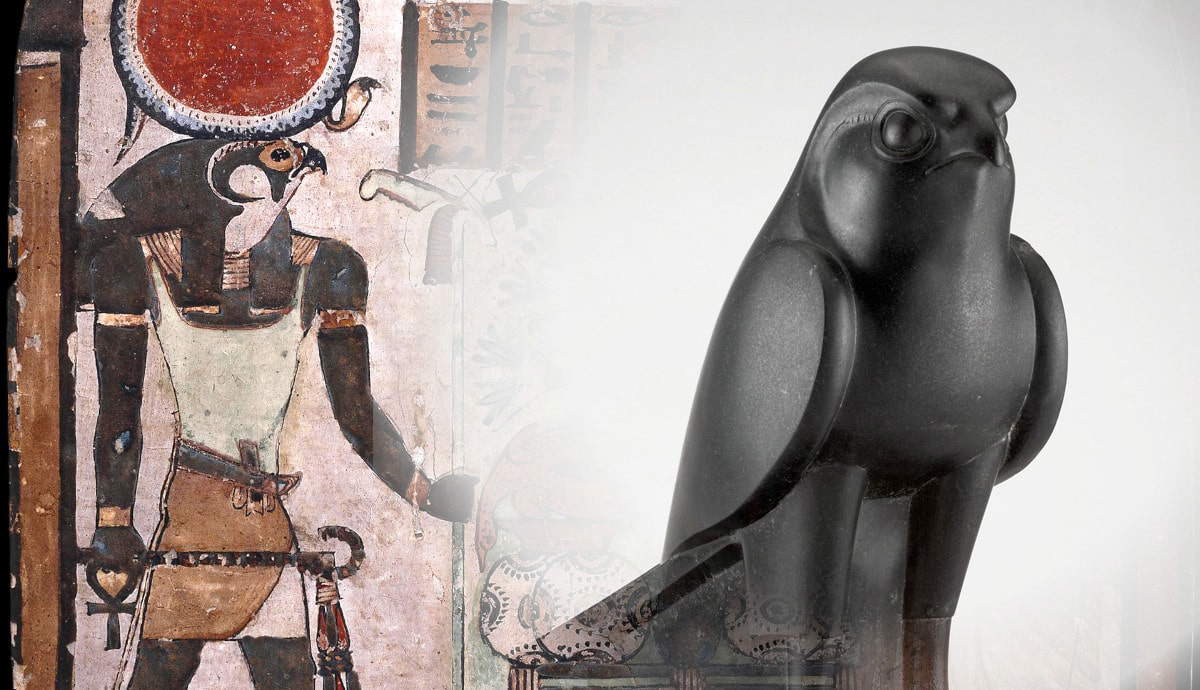

Heka was the god of magic, but sorcery was strongly also associated with Thoth, especially in later periods. Thoth was the god of wisdom, writing, and one of several gods of the moon. Through his lunar power, he was conflated with astronomy and astrology, which have historically been linked to magic. Additionally, Thoth was linked to healing through his role in the ancient Egyptian creation myth in which he heals Horus’s eye. Healing was another process heavily associated with magic in ancient Egypt. Doctors were intrinsically connected with magic as illness was often thought to have been caused by supernatural powers.

Many ancient Egyptians practiced magic by wearing amulets to ward off bad spirits. Dawn was believed to be the best time of day for spells and magical acts, and the practitioner needed to be in a state of purity. This meant that practitioners had to abstain from sex, avoid menstruating women, and if possible, clean themselves and put on clean clothes before engaging in spells.

Women and Magic

The evidence for the role of women in magic is ambiguous. Women were employed as mourners at funerals for the elite and were sometimes paid to maintain tombs. Within the funeral ceremony, two women could walk alongside the coffin to represent the goddesses Nephthys and Isis, who mourned Osiris in the creation myth.

There is no ancient Egyptian word for midwife or nurse, but the Ebers Papyrus, an Egyptian medical document from c. 1550 BCE, attests to the existence of midwives. Wealthier families often had live-in nurses, while for poorer women, a friend or family member would fulfill the role of midwife. Birthing bricks and chairs used for the mother during labor were usually decorated with images of goddesses. Correspondingly, midwives evoked the powers of multiple deities during birth, particularly Hathor, Bes, Taweret, and even Thoth.

The birthing room was also decorated with depictions of certain gods, and sometimes an ivory wand adorned with magical inscriptions was placed on the woman’s stomach. Furthermore, numerous birthing spells survive and utilize protective amulets. Bes amulets were often worn by women trying to conceive, mothers, and young children for protection. There is even evidence of women having the dwarf-god Bes tattooed on them.

“Wise women” could be consulted to interpret dreams, which was viewed as a supernatural practice. These women were skilled translators as the gods and the dead, who communicated via dreams, and typically did so in an illusive manner. Men could also translate dreams, but it seems to be a predominantly female field. The Temple of Hathor at Dendera, where the religious officials were mainly women, seems to have been a hub for dream interpretation.

Amulets and Symbols

Amulets and symbols were of utmost importance within ancient Egyptian culture. The main purpose of an amulet was to bestow its wearer with protection against evil forces or misfortune. Amulets in ancient Egypt were imbued with power by their shape, an inscription, material, or spells cast upon them. Amulets took many forms, but the Ankh, the Eye of Horus, and the Scarab Beetle are some of the most common forms. Amulets could also be found in a textual format, with short spells written on papyrus, folded or put on a string, and worn or placed in a person’s pocket.

The use of amulets is recognized as far back as 4400 BCE, and Egyptian designs have been found on amulets from the Roman era. The different colors of precious and semiprecious gemstones correlated with the purpose of the amulet. Red for protection against evil forces while blue and green faience was associated with regeneration. Gold and silver were often favored by the upper classes both for their durability and because they directly demonstrated their wealth. Equally, the iconography depicted on amulets could possess dual meanings. For example, the Djed pillar was used in architecture and represented stability and strength, but could also signify the human spine and was often found in the wrappings of mummies near the backbone.

Magical Objects

As well as amulets, many objects were believed to possess or were imbued with magical power. Iconography and religious imagery can be found decorating objects intended for everyday use such as mirrors and headrests, demonstrating how magic was intertwined with everything. Such objects were associated with particular deities and important magical elements. Mirrors, for example, were circular and made of bronze and were connected with the sundisk and regeneration, then later with Hathor and her beauty. Consequently, many mirrors from later periods possess handles in her image.

Steles and statues are renowned for their magical powers. An example is the Cippus of Horus, which details thirteen spells to cure venomous bites. The stela dictates that the victim should drink water that has been poured over the inscribed spells to cure themselves. Horus, Thoth, and Bes are all depicted on the stela, which would indicate its protective qualities to even an illiterate person.

Magical, apotropaic wands were common in the Middle Kingdom and were typically used in birthing rituals. Made of hippopotamus ivory, they are regularly inscribed with images of women, children, and protective deities. The hippopotamus itself represented Taweret, the hippopotamus goddess of childbirth and fertility. Interestingly, they have been most commonly found in tombs, which appears to suggest protective power related to rebirth in the afterlife.

Magic and Medicine

Medicine and magic were viewed as intrinsically linked in ancient Egypt. Supernatural powers were viewed as the source of ailments and also had the ability to cure. Moreover, the written word was considered magical. Being able to speak the name of the supernatural entity causing a person’s condition was believed to give the doctor power over them. Animal feces was used in a multitude of ancient medicines across Egypt. In some cases, it was used to lure demons out of human bodies because it was so foul. In other cases, sweet things such as honey were used to persuade supernatural beings out of the victim. A doctor could also draw an effigy of a deity on the sufferer so that they could lick off the image and ingest its healing power.

Another important element of medical practices was the use of recited spells alongside remedies and surgeries. These incantations were designed to ask the deities for help in the healing process. Doctors could provide these during private treatments whilst priests would hold larger ceremonies. Temples dedicated to gods associated with healing were places where people could seek medical advice and pray or give offerings to the deities in the hope of curing illness and injuries.

Egyptian medical papyri contain a plethora of examples of how magic and religious beliefs combined with science to cure ailments. The Ebers Papyrus explains how migraines could be cured by securing a clay model of a crocodile to a person’s head with a piece of linen inscribed with the names of various deities. Modern scientists have concluded this may have been an effective treatment through cold compression of the head.

Curses

Magic possessed many positive connotations, such as healing and protection, but curses were also common in ancient Egyptian society. Despite modern misconceptions, curses were not commonly found in tombs. “Tomb curses” were more warnings, letting people know the repercussions of certain actions, much like in Egyptian legal texts. Most of the curses found in tombs suggest the trespassers will not make it to the afterlife, but some inscriptions, especially from private tombs from the Old Kingdom, do make unique and rather chilling threats. The mastaba of Khentika Ikhekhi says he will seize an intruder’s neck “like a bird’s.”

Curses and dark magic are also found in other elements of society, particularly when dealing with foreign invaders. The practice of inscribing pottery, statuettes, and other clay objects with curses aimed at expelling or defeating foreign adversaries and then smashing them at ritual sites was common between 2600-1500 BCE. Known as “execration texts” or “proscription lists,” these objects could be broken into pieces, covered in urine, and burned in an official ceremony.

Similarly, the ceremony against Apophis consisted of creating wax effigies of the creature, which were trampled on and then destroyed using urine. Apophis (sometimes known as Apep) was a celestial serpent representing darkness and chaos and was the adversary of Ra and Ma’at. Human adversaries could be cursed by mimicking the divine ritual. Apophis also appeared in an annual rite called “the banishing of the chaos,” performed by priests. A large statue of the snake was burned to repel chaos for another year. Apophis is also mentioned in spells 7 and 39 in the Book of the Dead, which aided in protecting the dead from the serpent as they pass into the afterlife.

Magic and Death

Magical practices concerning death were significant in ancient Egypt. The Book of the Dead contains at least 192 different incantations, although no one copy contains every single spell. The purpose of this collection was to guide the dead person through the underworld, or Duat, and to protect them from deities, demons, and other dangers. The first Book of the Dead that we know of dates to the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), yet some of the individual spells date to the Old Kingdom (c. 2700-2200 BCE), which demonstrates how deep-rooted these beliefs were.

The Book of the Dead was often found amongst grave goods. Amulets and other written spells have also often been located within the wrappings of mummies. The ancient Egyptian concept of the soul, or Ka, is complicated, but in simplified terms, the Ka was the vital essence that originated from the chaos magic from which the world was created and inhabited every human. A person died when their Ka left their body. Moreover, it was the Ka that lived on after death, and food and drink were brought by the living as offerings to sustain it.

At different points in Egyptian history, the soul was believed to consist of up to nine components. Another of the most significant parts was the Ba. Typically described as the individual’s personality, it generally encompassed everything unique about a person. It usually appeared as a bird with a human head. After a person died, the Ba and Ka came together to form the Akh, which represented the deceased as a whole if proper funerary rituals were maintained. It became a sort of ghost that would live on and could be called upon to settle disputes. It could impact the living positively or negatively and it was often associated with both good luck and nightmares.

As can be seen, the ancient Egyptians believed that the supernatural and magic were a fundamental part of existence and engaging with the supernatural, through magic, was a necessary part of daily life. Magic wasn’t superstition, but rather a logical way to deal with life’s challenges based on their understanding of the world.