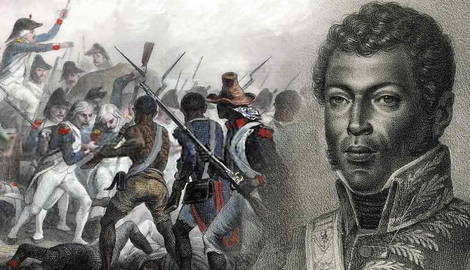

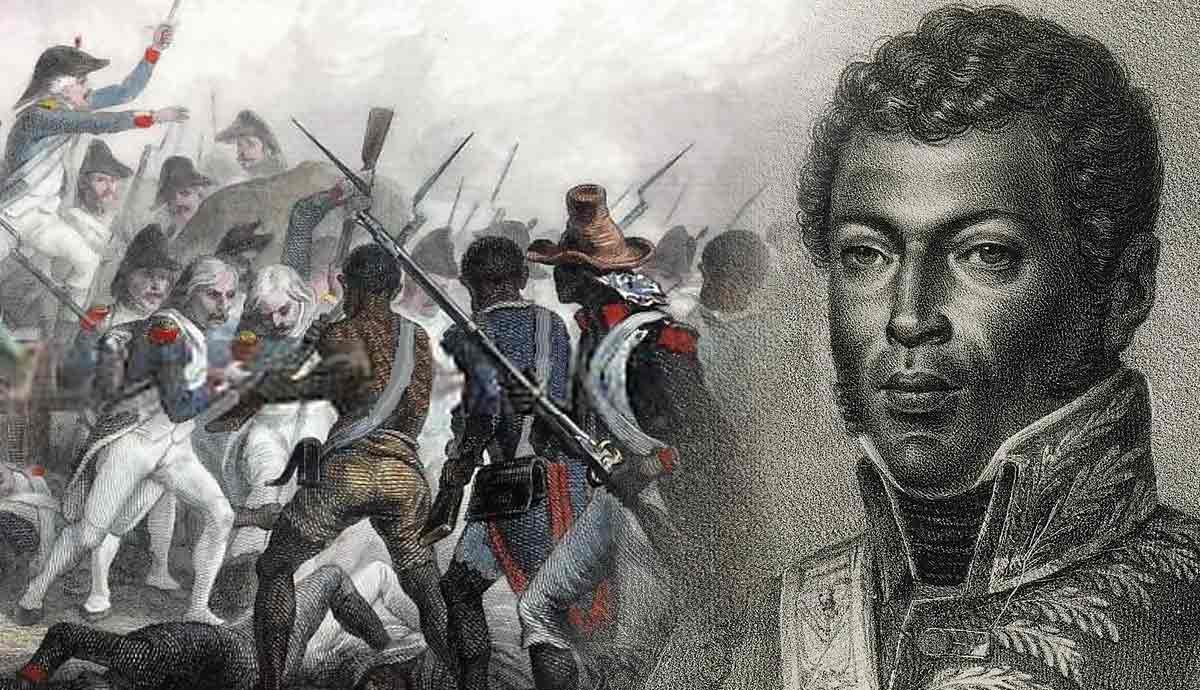

The Haitian Revolution was the only slave revolt in history that successfully established an independent state free of slavery and ruled by the formerly enslaved. The people of Haiti were subject to horrific treatment by the ruling white French population, and their fight for freedom crushed the widely held belief of white superiority. Numerous figures, diverse in backgrounds and beliefs, were influential in the course of one of the most important events in human history.

1. Toussaint Louverture

Toussaint Louverture, despite supposedly descending from African royalty, was born enslaved in Haiti in 1743. At the age of 33, he was granted his freedom and went on to amass a modest fortune. He rented a small plantation and a number of slaves, consequently profiting from the same enslavement he himself was once subjected to.

While the French Revolution spread across France, Haiti was disregarded by its imperial overlord. As a result, conditions on the island, especially for slaves, quickly deteriorated. Louverture, alongside other prominent Haitian figures, played an important role in planning a revolt against the French.

Upon the outbreak of the revolution, he forged an alliance with Spain, gained significant military experience, and became a prominent leader among Haitians. During the 1790s, Louverture’s views shifted. Previously, he had only wished to improve conditions for slaves; however, as the revolution continued, he began campaigning for abolition.

Following the French Revolution, the new French Republic abolished slavery. Meanwhile, Louverture’s relations with the Spanish began to deteriorate. As a result, Louverture switched allegiance to the French Republic.

By the 1800s, Louverture controlled significant territory in the south of Haiti. However, when Napoleon rose to power, concerns spread that slavery would be reimposed. In response, Louverture drafted a constitution in 1801 that declared almost absolute power for himself over the entire island of Hispaniola.

Outraged, Napoleon sent a force of 40,000 men to reestablish control of Haiti. Louverture was captured in 1802 and sent to France. He died in a French prison a year later.

2. Dutty Boukman

On August 21, 1971, a Vodou ceremony was held at Bois Caïman that was attended by hundreds of enslaved people. Vodou, also known as voodoo, is a Haitian religion that blends numerous African traditions and beliefs.

The ceremony was led by Dutty Boukman, who was a male Vodou priest known as a Houngan. Little is known of Boukam’s origins, though it is speculated that he was born in West Africa, likely in Senegal, and was first taken as a slave to Jamaica. It is believed he was literate and taught other slaves to read, hence the origin of his name, “Boukman.” Supposedly, Boukman was caught plotting a revolt in Jamaica, so he was sold to a slave owner in Haiti.

At the ceremony, Boukman declared the beginning of the revolution and led the attendees in prayer. The Haitian Revolution began the following day. Boukman was killed during the fighting just one month later. French forces displayed Boukman’s severed head in hopes of deterring further rebellion.

3. Cecile Fatiman

Cecile Fatiman led the Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman alongside Dutty Boukman. Fatiman’s early life is heavily speculated. Some believe she was the daughter of a Corsican Prince, the son of King Theodore I of Corsica, and an enslaved African woman.

At a young age, Fatiman trained to become a Vodou priestess and participated in prayers and animal sacrifice. She became a Mambo, the title of a Vodou Priestess.

Fatiman went on to marry Jean-Louis Pierrot, who would later become the fifth President of Haiti, though the couple divorced years prior to his election. She reportedly died at the age of 112.

Together, Fatiman and Boukman played a critical role in the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution. They inspired the enslaved people of Haiti to rise up against their oppressors and used their affinity to the Vodou religion to instill a sense of higher purpose in the cause.

4. Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines was one of Toussaint Louverture’s most important lieutenants during the revolution. When French forces invaded Haiti under Napoleon’s orders, Dessalines won a decisive victory against French General Charles Leclerc at the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot. However, following the battle, Dessalines abandoned Louverture and sided with the French. Some historians even suggest that Dessalines played a role in helping France capture Louverture.

When it was realized that the French intended to reimpose slavery in Haiti, Dessalines once again opposed the French. Following Louverture’s capture, Dessalines became the leader of the revolution and led Haitian forces against the French invasion.

On November 18, 1803, Dessalines won another decisive victory against the remaining French forces at the Battle of Vertières. French forces officially departed the following month, signifying Haitian Independence.

Dessalines proclaimed himself Emperor of Haiti, styling himself Jacques I. Modeling himself on Napoleon, Dessalines’ rule was heavily autocratic. In 1804, he orchestrated a massacre against the remaining French settlers in Haiti, which led to the deaths of approximately 5,000 people. Dessalines was murdered in 1806 by political rivals. Though his rule was tyrannical, he is still recognized as one of the founding fathers of Haiti.

5. Georges Biassou

Georges Biassou was one of the early leaders of the revolution upon its onset in 1791. Like many of Haiti’s leaders, such as Louverture, Biassou allied with the Spanish to fight against the French. However, while Louverture switched allegiance back to the French, Biassou remained loyal to Spain.

Spain and France were at war with each other as part of the French Revolutionary War and the War of the Pyrenees. During this period, the island of Hispaniola was divided, with France controlling the west of the island, which they called Saint-Domingue (Haiti), and the Spanish controlling the east, called Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic). As a result, the island of Hispaniola and the ongoing Haitian Revolution became a battleground of this wider conflict.

Thus, Biassou now fought against not only the French but also his former Haitian allies, such as Louverture. Biassou was one of the leaders of Spain’s Black Auxiliaries, and he received weapons, supplies, and money to fight against the French.

In 1795, at the Peace of Basel, Spain and France agreed to end the War of the Pyrenees. As part of the peace, Spain agreed to cede their control of Santo Domingo to France.

With the war over, Spain disbanded the Black Auxiliaries, and as a reward for his service, Biassou was given Spanish citizenship. He and his family left Haiti and relocated to St. Augustine, Florida, which was then under Spanish control. He was made leader of the Black Militia of St. Augustine and would defend Floridian territory from attacks by Seminole Indians.

6. Andre Rigaud

Andre Rigaud was born to a rich French father and a Black mother who was a former slave. Recognized by his father as his legitimate mixed-race son, known at the time as a “mulatto,” he was sent to Bordeaux, France to train as a goldsmith. However, Riguad joined the French Army and fought in the American War of Independence, serving alongside French-Haitian troops stationed in Savannah, Georgia.

With his newly gained military experience, he returned to Haiti to fight in the revolution. He fought against British forces that attempted to invade Haiti in 1794. By 1796, Rigaud controlled much of the south of Haiti, with Louverture controlling the north. Tensions quickly arose between the two leaders. Rigaud was a proponent of Haiti’s race-based social hierarchy and that it should be maintained, with whites at the top, mixed race-mulattos below them, and Black Haitians at the bottom.

In contrast, Louverture wanted the eradication of this hierarchy. With the two now ideologically opposed, they fought against one another for control of Haiti. Known as the War of Knives, Haiti’s civil war, lasting for one year between 1799 and 1800, was won by Louverture. Rigaud fled to France.

Rigaud returned to France with Charles Leclerc’s expedition, which Napoleon sent. When the French incursion was defeated, Rigaud once again returned to France. At one point, he was arrested and held in the same prison in which Louverture had died. However, Rigaud was released. In 1810, he returned to Haiti yet again and attempted to establish himself as President of the south, though he was unsuccessful. He died the following year at the age of 50.

Andre Rigaud is a complex figure in Haitian history. While he fought for Haiti against its enemies, he remained observantly loyal to the racial status quo.

7. Alexandre Petion

Born in 1770 to a white Frenchman and a free mixed-race woman, Alexandre Petion was sent to France to study at the Military Academy in Paris when he was 18. He returned to Haiti upon the outbreak of the revolution and fought against the British invasion in the north in 1794.

As a mixed-race man, he allied with Andre Rigaud and fought against Louverture during the War of Knives. Alongside Rigaud, he went into exile in France after their defeat. He returned to Haiti in 1802 alongside Leclerc’s expedition. After Louverture was captured, however, Petion left the French and joined the nationalist forces, becoming a vocal supporter of Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

Petion supported Dessalines for the continuation of the war. Following Dessaline’s murder in 1806, he began advocating for the introduction of democracy to Haiti. This led him to clash with fellow revolutionary Henri Christophe. Petion was elected President of the Southern Republic of Haiti in 1807. Over the next few years, he struggled for control against Christophe. Eventually, a peace treaty was signed in 1811, which split Haiti into two parts, with Henri Christophe becoming King of Haiti in the north.

Despite his advocacy of democracy, Petion made himself “President for Life” in 1816 because he felt constrained by Haiti’s Senate. He died of yellow fever in 1818 and is recognized as one of Haiti’s founding fathers.

8. Sanité Bélair

Bélair was born a free woman of color. At the age of just 15, she married Charles Bélair, the nephew of Louverture, who would serve as a general during the revolution. Alongside her husband, Bélair would play an active role in the fighting. First, she became a sergeant and later rose to the rank of lieutenant during Leclerc’s expedition.

During the French invasion, Bélair and her husband were captured. On October 5, 1802, they were sentenced to be executed—Charles via firing squad and Sanité via decapitation, as custom for a woman. Sanité, however, demanded she be executed by firing squad like her husband. In an act of defiance, she refused to be blindfolded at her execution. While being walked past the gathered crowd, she reportedly shouted, “Liberty, no to slavery!”

Described by Jean-Jacques Dessalines as a tigress, Bélair remains an enduring figure of the Haitian Revolution. Her contributions to Haiti’s freedom were recognized in 2004 when she was featured on Haiti’s Ten Gourdes banknote.

9. Léger-Félicité Sonthonax

A French native, Sonthonax worked as a lawyer in the Parliament of Paris during the outbreak of the French Revolution and was well-known for his views in support of abolition. In 1792, the new French Republic sent him as a member of a civil commission to Haiti, where he was tasked with granting full French citizenship to all free people of color, reasserting French authority, and reinforcing the rule of law.

However, upon his arrival, he allied himself closely with Haiti’s freed slave population. Controversially, he closed Haiti’s colonial assembly, which was entirely comprised of white members, and even exiled white settlers who refused to accept the new equality measures he imposed.

A year later, the Governor of Haiti, who was a loyalist to the deposed French Monarchy, incited riots led by white settlers. In response, Sonthonax promised freedom to any Black slaves who would fight on behalf of the French Republic.

When the Governor was forced into exile, Sonthonax decreed the abolition of slavery in Haiti’s northern province. A few months later, his ally and fellow commissioner, Étienne Polverel, abolished slavery in the west and south. Sonthonax also opened negotiations with Louverture, which resulted in the Haitian general realigning with the French Republic.

Sonthonax and Polverel’s actions were deeply controversial to the white settlers in Haiti, and many sent petitions to the French National Convention, which indicted the two commissioners. Sonthonax and Polverel left Haiti in 1974.

After successfully defending himself in front of a commission, Sonthonax returned to Haiti two years later. By this time, Louverture was consolidating his power and did not wish Sonthonax to interfere. Louverture had Sonthonax elected Deputy of Saint-Domingue at the Council of Five Hundred, which convened in Paris, thus keeping Sonthonax away from Haiti.

When Napoleon seized power in 1799, Sonthonax was exiled from Paris. He returned to his hometown, where he died in 1813. Léger-Félicité Sonthonax played a crucial role in the abolition of slavery in Haiti, as well as the shaping of its political landscape during the revolution.

10. Charles Leclerc

Charles Leclerc was famous for being Napoleon’s brother-in-law after marrying his sister Pauline. An accomplished General, Leclerc had extensive experience fighting in the French Revolution.

When Louverture announced his constitution in 1801, Napoleon sent Leclerc to Haiti to restore French control. Leclerc arrived in Haiti with approximately 40,000 troops under his command. Quickly, he gained the alliance of numerous Haitian leaders, including Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Alexandre Petion.

Leclerc won several conclusive victories against the Haitian forces and successfully regained control of much of Haiti. This forced Louverture to enter negotiations with Leclerc, which resulted in the Haitian general being placed under house arrest before he was eventually sent to France as a prisoner.

Despite being seemingly victorious over Louverture, Leclerc failed to impose his authority over Haiti, and the violence continued. Leclerc petitioned Napoleon requesting permission to conduct a “war of annihilation” against Haiti, even suggesting killing all Black Haitians over the age of 12 to ensure submission to France.

Haitians who had agreed to fight under Leclerc mutinied en masse, which eventually led to Leclerc executing 1,000 black Haitian troops under his command. Before Leclerc could inflict further bloodshed on the Haitian people, he died of yellow fever in 1802.

The people who influenced the Haitian Revolution were diverse in their motivations. Some fought purely for their liberty and freedom, some fought to reimpose bondage and authority, while others fought solely for their own ambition. The Haitian Revolution was a complex conflict, with a near-constant shifting in alliances on top of an ever-evolving political landscape. From the indomitable figure of Toussaint Louverture to the ruthless Charles Leclerc, these figures have ingrained themselves into the history of Haiti and the struggle for emancipation.