Of the three great medieval West African states — Ghana, Mali, and Songhai — it is the Empire of Mali that has most captured the popular imagination. Mali grew out of some incredible (yet also disturbing) forms of trade and the interaction of the Islamic religion with pre-existing West African cultural practices. Unlike the modern country of Mali, the medieval empire stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Niger River. Right behind the later Songhai Empire, it was one of the largest states in pre-modern African history.

If the Empire of Mali were so important during its own time, how does its legacy continue to affect the present day? It turns out that even though the state itself collapsed, Mali’s culture did not. Across the nations of West Africa, elements of Malian culture have survived and adapted to changing conditions.

The Empire of Mali Was a Multi-Religious State

The Malian Empire’s territories spanned the western part of the Sahel — a large region of Africa directly below the Sahara Desert. In this area, religious exchanges have occurred throughout history. In the case of Mali, these interactions involved local ethnic traditions and the religion of Islam.

As early as the eighth century, North African Arabs had brought Islam to parts of the Sahel. In some states, rulers and nobles families converted, but the rural population largely did not. Some ethnic groups were also more receptive to the northerners’ preaching than others. West Africa’s total transformation into a bastion of the Islamic faith would take over one thousand years.

In the Sahel, early Islam had to adapt to pre-existing local belief systems. Muslim religious men might inscribe verses from the Qur’an onto talismans and amulets — adding an Islamic coat of paint on top of an already existing structure. The Empire of Mali’s ruling Keïta clan, for example, started to base its legitimacy on the supposed arrival of an ancient Muslim founder to West Africa. Despite their often-major differences, Islam and local traditions came to build on each other in Malian history.

The Gold Trade Dominated Medieval Mali’s Economy

The Empire of Mali’s economy was centered on a particularly precious resource: gold. The Malian emperors (Mansas) controlled several major goldfields in the western Sahel. Because of this, gold dominated the Malian side of the trans-Saharan trading network. Arab and European states at this time had started to make coins from gold, some of which must have come from Mali.

Trade was actually the main vehicle that facilitated the spread of Islam in West Africa. Merchants from the north and east brought the religion with them, converting the locals. This stood in contrast to the situation north of the Sahara, where Muslim armies spread their faith as they conquered new territories.

The Malian economy was not without its dark side, however. Slavery, which had long existed across the Sahel, was a reality of life in the empire. The slave trade formed another branch of the trans-Saharan network, supplying North African slavers with captives. Over time, slavery developed into a hereditary status in parts of the region. Discrimination against descendants of slave castes still exists in modern Mali, in spite of slavery’s abolition.

Islam Fueled the Development of Regional Scholarship

Once Islam had established a firm presence in the Empire of Mali, Muslim scholars founded schools and centers of higher learning. Cities such as Timbuktu became major centers of Islamic scholarship. Madrasas (Islamic schools) and libraries housed thousands of manuscripts covering a wide array of topics, both religious and secular. Malian rulers even provided these institutions with funding. The most famous madrasas in Timbuktu included Sankoré, Sidi Yahya, and Djinguereber.

Support for Islamic scholarship continued after Mali’s decline. The Songhai Empire, under the Askiya dynasty, was perhaps the most prolific funder of manuscript production. Despite periodic revivals, however, Timbuktu did gradually lose its central importance. By the seventeenth century, the city’s prominence had long since faded. Only the memory of a once obscenely wealthy town remained.

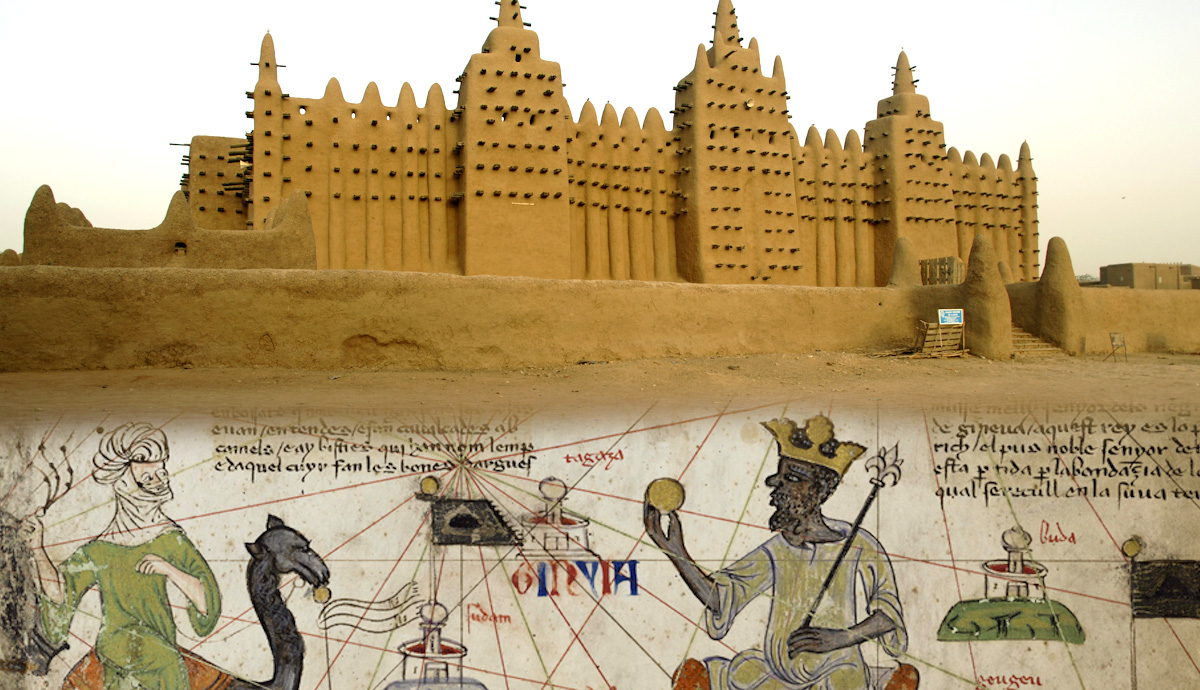

One of Mali’s Rulers May Have Been the World’s Wealthiest Man

If you’ve heard only one thing about the Empire of Mali, it’s probably the name of its most famous leader: Mansa Musa. This Malian emperor was renowned among contemporary Arab and European writers for his immense wealth. One commentator, the Syrian historian Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari, described Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324-26. He paid particular attention to Mansa Musa’s stop in Cairo, Egypt. Musa allegedly gave away so much gold in Cairo that the local value of the precious metal crashed for twelve years!

Is this story true? Probably not entirely. Some modern writers have labelled Mansa Musa as the wealthiest person in history, but we have no way of measuring his exact wealth. What is probable, however, is that he was the wealthiest ruler of his time. His legendary hajj literally put him on the map in Europe and the Islamic world. He was, quite possibly, the John D. Rockefeller of the fourteenth century.

Mali May Not Have Had Just One Capital City

The Empire of Mali may have been extremely wealthy under Mansa Musa, but surprisingly we don’t know where its capital city was. Historical sources give different locations. The Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta visited the Malian capital, but even he does not offer a solid location. If we are to believe the Arab chroniclers, the capital city could have been anywhere across the western Sahel.

Certain towns, such as Timbuktu and Gao in Mali and Niani in modern Guinea, definitely became particularly renowned during the medieval period. Still, historians and archaeologists can’t seem to agree on where the Empire of Mali’s center of power was. Could it have changed based on who was the Mansa at any given time? Or have archaeologists just not had the chance yet to conduct proper fieldwork? Whatever the answer is, the empire’s capital remains unknown.

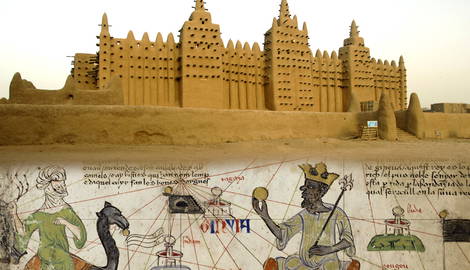

Malian Architecture Remains in Use Today

Part of the Empire of Mali’s most enduring legacy lies in its architecture. Medieval West African architects largely built with mudbricks due to the dearth of available stone in the region. The mudbrick structures that survive today notably include wooden beams on their exteriors. This allows for community masons to climb up to reinforce the buildings with new mudbrick, which has to be done regularly.

The best-known examples of Sahelian architecture from the Empire of Mali are all Islamic institutions. Chief among these is the Great Mosque of Djenné, in south-central Mali. The building’s current iteration dates back to 1907 but records indicate previous versions of the structure have existed there for centuries. The three madrasas of Timbuktu — Sankoré, Sidi Yahya, and Djinguereber — were also constructed in this style. Islamic Sahelian buildings can be found from Senegal and Mali in the north to as far south as modern Ghana and Nigeria. Their materials may be more fragile than stone or steel, but they have evidently retained their great cultural importance in order to survive.

Storytellers Continue to Pass Down the Empire of Mali’s History

Prior to the spread of Islam, the people of the Sahel did not record their histories in writing. Instead, they passed down narratives orally, from generation to generation. This oral tradition remains strong and prevalent in West African countries today. At its center are a caste of people known as griots (jaliw in the indigenous Mandé languages). Their whole occupation is to preserve the cultural heritage of their people.

Jaliw do not have one single function in West African society. From early childhood, they train in a variety of fields: music, oral poetry, performance, and community history. Common instruments played by jaliw include the harp-like kora and the balafon, a large cousin of the xylophone. A jali inherits his position from his father. Female jaliw remain rare in patriarchal Sahelian societies, although some, such as British-Gambian musician Sona Jobarteh, have achieved success.

Jaliw have historically been endogamous; societal taboos prevented them from marrying outside their social class. This persists to an extent in the modern world. During the medieval era, every ruler had a personal jali, who embraced and memorized the royal genealogy. It was the job of the jaliw to provide counsel to their leaders. Modern jaliw are mostly known as musicians and performers, however.

To Western audiences, the jaliw’s most prestigious contribution has been the Epic of Sundiata. This vast epic poem recounts the legendary foundation of the Empire of Mali in the thirteenth century. It is a story of good vs. evil, friendship, conquest, social duty, and triumph over adversity all in one. Djibril Tamsir Niane’s version of Sundiata, originally published in 1960, is the best known, but countless other versions exist as well.

As an oral tradition, the story of Sundiata has evolved over time, depending on its performer and audience. One jali might include small details or references particular to his own experiences. Yet various jaliw have upheld the core tenets of the Sundiata tale for more than seven hundred years.