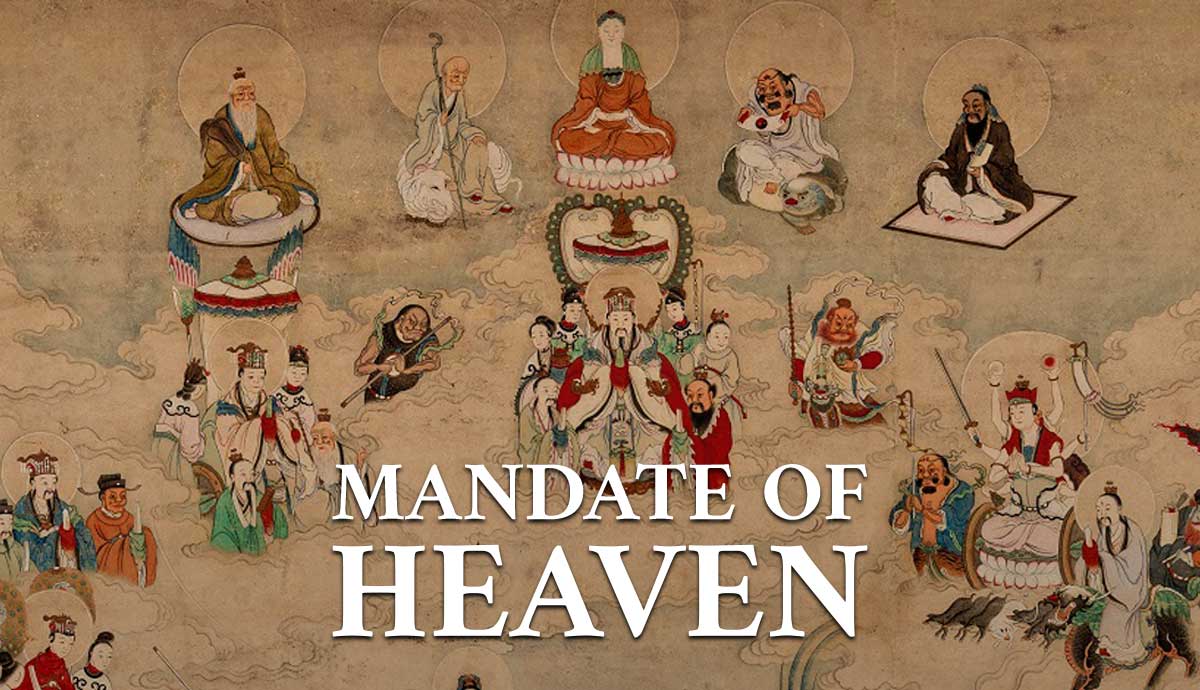

The Emperor of China stood at the apex of the Chinese social order. Regardless of which dynasty was in power, the emperorship was almost a constant for over 2,000 years of Chinese history. He possessed both worldly and spiritual importance; it was his job to govern China in accordance with the rule of the universe.

Imperial political theorists and religious figures devised a complex ideology to determine why an emperor had the right to rule: the Mandate of Heaven. The Chinese emperor had command over everything—but as we will soon explore, he had potentially everything to lose as well.

When Did the Mandate of Heaven Develop?

The Mandate of Heaven is an ancient concept in Chinese culture. Historians believe it was first formulated during the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046-256 BCE). The Zhou kings devised the theory in order to explain and justify their rebellion against the previous Shang dynasty. The Shang rulers, they reasoned, had fallen out of favor with the divine order, and could therefore be replaced.

Later dynasties developed the Mandate of Heaven doctrine further. Its importance to Chinese political thought changed over time, playing a much more central role in some dynasties than others. However, it persisted as imperial ideology for more than 2,500 years.

What Was Heaven in Chinese Theology?

Chinese religious culture is unique among the world’s spiritual systems. The Chinese people have revered countless deities over the millennia, but none of them ever completely superseded the others. The concept of “Heaven” in Chinese religion is also entirely different from Heaven in the Abrahamic religions.

The Chinese word for Heaven is Tian. It usually refers to something beyond the scope of ancestors and elemental gods—the very order of the universe. It is impersonal, lacking a defined shape or human-like attributes. Some historical Chinese thinkers associated Tian with the concept of Shangdi (the highest spiritual ruler), but this was not always the case. More often, Tian meant the balance of the cosmos.

Chinese dynasties upheld a doctrine which described the emperor as the Son of Heaven. Emperors were effectively demigod figures; it was the people’s duty to obey and revere them, as they would local gods or their own parents. The Japanese would develop a similar concept later surrounding their own emperors. In Japan, though, the imperial family claimed direct divine origin. This was a step beyond the Chinese Mandate of Heaven.

Who Could Hold the Mandate?

The question of who could legitimately hold the Mandate of Heaven kept Chinese philosophers up at night. But put most directly, only one ruler could claim the Mandate of Heaven at any particular time. If another leader outside the upper echelons of power contested the emperor’s legitimacy, they would be dealt with severely. The emperor’s family would then hold the Mandate until the universe decided their time was up.

No dynasty had the divine right to rule for all eternity. A dynasty’s founding emperor also didn’t have to come from a noble background, unlike in countries such as Japan or France. Some of China’s best-known emperors actually came from ordinary backgrounds. The Hongwu Emperor, founder of the Ming Dynasty in 1368, was the son of farmers.

If an emperor failed to serve his people justly or uphold the proper rituals, he risked losing the Mandate of Heaven. The Chinese viewed natural disasters, epidemics of disease, famines, and wars as possible signs that a dynasty had lost the Mandate. If any of these were to occur, it became legitimate to rebel against the ruling dynasty and restore the natural and social order.

Revolution and the Change of Dynasties

The downfall of an imperial dynasty represented a monumental shift in Chinese history. In general, the major dynasties after the Qin and Han eras seem to have tried to maintain some ideological continuity with China’s past. At the same time, they established themselves as supreme, often by destroying the records and monuments of their predecessors. Yet every dynasty after the Zhou rooted their legitimacy in the Mandate of Heaven doctrine. This included dynasties of non-ethnic Chinese origin, such as the Yuan and Qing.

The Qing Dynasty’s take on the Mandate of Heaven represents an especially intriguing case study. When this ethnically Manchu clan seized power in the mid-17th century, they didn’t do so from the previous Ming Dynasty itself. They actually took the Mandate from Han Chinese rebels who had brought the Ming down.

These rebels had been motivated by the Ming emperors’ inadequate response to frequent natural disasters and poverty. The Manchus exploited divisions among the insurgent factions to forge powerful alliances. In 1644, they and their Han Chinese allies conquered Beijing. The Mandate of Heaven had passed on to the Manchu Aisin Gioro Clan, they claimed.

The new Qing Dynasty had to carry out a difficult balancing act. As members of an ethnic minority, the Manchu emperors were aware of their status as outsiders. Yet they combined their drive to maintain their cultural distinctiveness with efforts to adopt Chinese cultural practices and terminology. Claiming to rule China under the Mandate of Heaven was the most straightforward path to political legitimacy.

The Confucian Twist on the Mandate

During the Zhou Dynasty, China witnessed the birth of the Confucian tradition. With its emphasis on individual and collective morality and relationships, Confucian thought remains one of China’s greatest intellectual contributions to the human experience. As it developed over time, it commingled with the older doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven.

Confucian philosophy dealt significantly with statecraft, more so than Daoism and other Chinese schools of thought did. After all, the sage Confucius himself had attempted to forge a career in politics. He did become an advisor to several local rulers, but his grand political ambitions didn’t play out the way he wanted them to. Still, Confucius never relinquished the value he placed on proper political conduct.

Confucian ideals of proper political conduct frequently merged the spiritual and the worldly. The sage and his immediate followers weren’t especially concerned with the worship of gods, but they did believe in upholding specific rituals. Maintaining practices like the veneration of ancestors, for example, was essential for a moral society. Rituals did honor the divine, but more importantly, they upheld communal unity. The idea of an impersonal Heaven—a cosmic order based on a hierarchy of relationships and interpersonal obligations—meshed well with Confucius’ teachings.

The Mandate of Heaven and Non-Chinese Traditions

Confucian thought dominated the intellectual environment of imperial China. Yet throughout Chinese history, different belief and ritual systems have tended to blend together rather than stay strictly apart. Thus, Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucian philosophy intermingled and came to share the concept of the Mandate of Heaven. This occurred to a smaller degree with non-Chinese religions as well.

Take the example of Chinese Christianity. When Catholic Jesuit missionaries started to arrive in China in the late 16th century, they tried to set up a new religion in an already complex spiritual stew. Chinese converts to Christianity were well aware of the theological gaps between their own ancestral traditions and the Catholic Church’s exclusive monotheism. So they sought to find a rationale for the two cultures’ compatibility.

One Chinese Christian convert, the scholar Li Zhizao, believed that Chinese Confucians, Daoists, and Buddhists failed to understand the true nature of Heaven. Li had met Matteo Ricci, the Italian Jesuit priest who led the Church’s earliest Chinese missions and accepted Christian baptism. According to Li’s beliefs, the Catholic doctrine of God completed the Chinese concept of Heaven: “In explaining Heaven, no book excels the Classic of Changes, the source of our written characters. It says that the primal power (Qianyuan) that governs Heaven is the king and father of all” (De Bary et. al., 2000).

Notice Li’s effort to complement the impersonal Heaven with a personal creator. His citation of the Confucian Classic of Changes is deliberate, firmly rooting his thought in classical Chinese philosophy and practice. Other Confucian scholars of his time, he argued, were familiar with the Mandate of Heaven and the nature of the cosmos, but ordinary Chinese people were not. Li effectively endorses the Jesuits’ missionary presence, urging the Chinese to investigate conversion to Catholicism. In Li Zhizao’s mind, Confucian thought still held great wisdom and value to Chinese culture, but its understanding of the divine was incomplete.

How Did the Mandate of Heaven Shape Chinese History?

As an ideology, the Mandate of Heaven guided Chinese statecraft during the expansive imperial era. Much like the divine right of kings in Europe, the Mandate of Heaven bestowed upon the Emperor of China a religious function. His rule was natural law. However, at least theoretically, the ruling dynasty’s power was not completely absolute. Acting too harshly toward the people or standing down in the face of natural disasters could spell the end of a dynasty. A new one could then rise up and claim the Mandate of Heaven.

The enduring legacy of Confucian ideology continues to define Chinese (and greater East Asian) culture. Today, China’s Communist government no longer bases its legitimacy on the Mandate of Heaven. The emperors of old are long gone. However, the Mandate was hugely influential for Chinese political philosophy for more than two thousand years. It underpinned powerful dynasties and merged the secular and the sacred in a unique way.