British rule in India is a complex subject that elicits strong emotions in various contexts. This period of Indian history was marked by brutality, oppression, and the loss of dignity. It has indelible permanence on the psyche of the Indian nation and has been the topic of countless studies in the realm of academia.

One traumatic event was the Indian Mutiny of 1857, which involved actions taken by a man named Mangal Pandey.

Where Did Mangal Pandey Come From?

The events of the Indian Mutiny cannot be studied without looking at the context in which it happened and the world in which Mangal Pandey found himself when he decided to take the fateful actions that would plunge the subcontinent into rebellion.

Mangal Pandey was born on July 19, 1827 to Abhairani and Divakar Pandey in the village of Nagwa in what is now Uttar Pradesh. He had a sister who perished in 1830 due to famine.

The British East India Company had been operating in India for 70 years already, and conflict was common as Britain attempted to stamp its authority over India. This involved not just conflict with the native population but also with other colonial powers.

Thus, the Indians found themselves subjugated by foreigners and treated as inferiors in their own land. This provided a starting point for discontent that would grow over the decades.

Mangal Pandey had a good start in life as he was born into a land-owning, high-caste Brahman family. This was the Hindu priest caste, so Mangal developed a deep devotion to religious tradition.

Little is known about his childhood, and information on his family is difficult to come by. Although of a higher caste, his family was likely of peasant means, as was common in the rural area where Mangal grew up.

He was ambitious, courageous, and had a strong sense of honor. At the age of 22, he joined the military. In 1849, he encountered a brigade of soldiers employed by the British East India Company, and he decided to enlist. As a soldier (sepoy) in the 6th Company of the 34th Bengal Native Infantry, he was surrounded by many other Brahmans who were also assigned to his company.

What Did Mangal Pandey Do?

By the late 1850s, discontent was rising in the ranks of the sepoy armies in the employ of the East India Company. This was caused by a series of factors, including poor salaries, lack of promotions, and general racial and cultural insensitivity from British officers.

Mangal Pandey became disaffected by the British’s poor treatment of sepoys. His actions snowballed far beyond his control and turned into a major, nationwide rebellion that threatened British rule in India.

The spark that led Pandey to object to the poor treatment of sepoys was the introduction of the new Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket, or more specifically, the cartridges that were made for it.

Loading the gun required the user to tear off the end of the cartridge with his teeth before pouring the gunpowder down the barrel. To prevent the cartridges from sticking together in storage and lubricating the bullet in the barrel, the cartridges were greased with animal fat.

Rumors began to circulate that the fat was derived from cows and pigs. This presented a particular problem for both Hindus and Muslims, who regarded it as an insult to their religious sensibilities. They believed the British had done this deliberately.

Mangal Pandey, Agitator

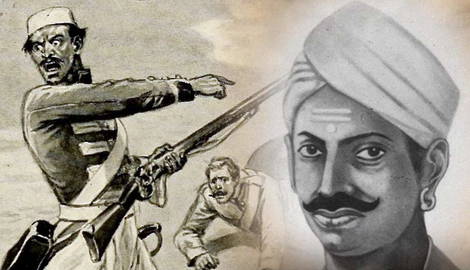

The defining incident involving Mangal Pandey occurred in the barracks of the 34th Bengal Native Infantry in Barrackpore. Lieutenant Baugh, a regimental adjutant, received word that many men in his regiment were agitated. He mounted his horse and rode to where the reports of the disturbance had come from.

Mangal Pandey was pacing up and down outside the regimental guardroom armed with a loaded musket and shouting at the other soldiers, inciting them to rise against the British. He was also threatening to shoot the first European he saw—a promise he would attempt to keep.

According to an inquiry after the fact, it was determined that Pandey was not in a normal state of mind. He was under the influence of a narcotic called bhang, an edible preparation made from the leaves of the cannabis plant. Upon hearing that a detachment of British soldiers had disembarked from a steamer near the barracks, he was spurred into action. During his trial, he also claimed that he had been smoking opium.

Fearing a fight was about to break out, a sepoy corporal had informed British Sergeant-Major Hewson, who arrived on the parade ground where Pandey was and ordered Pandey to be arrested. Jemadar Ishwari Prasad informed the sergeant-major that he could not take Pandey alone and that his NCOs had gone for help.

At this point, Baugh arrived, and Pandey was already prepared for a fight. He had taken position behind the station gun, and when he spotted Baugh, he took aim and fired. The shot missed Baugh but hit Baugh’s horse. Baugh and his horse tumbled to the ground, and Baugh freed himself before firing his pistol at Pandey, who was now advancing towards the lieutenant. His shot missed, and before he could draw his sword, Pandey was upon him.

Pandey slashed with a heavy, curved sword called a talwar. The blade caught Baugh on the shoulder and brought him to the ground. Hewson attempted to bring Pandey down, but Pandey struck him with the butt of his musket, and Hewson fell to the ground too.

Before Pandey could make another attack, a sepoy, Shaikh Paltu, ran up and tried to restrain him. By this time, a crowd of spectators had gathered and pelted Shaikh Paltu with stones as he tried to help the two British officers. Some of the spectators then assaulted the two officers as they lay on the ground.

Word of the fight reached the ears of the commanding officer, General John Hearsey, who rushed to the location with two of his officer sons in tow. When he reached the scene, he ordered the sepoys to apprehend Pandey, threatening to shoot any who disobeyed his orders.

They prepared to follow his orders and approached Pandey, who, by this time, had reloaded his musket. He pointed the barrel at his chest and pulled the trigger with his foot. Although bleeding profusely, the injury was not fatal, and Pandey was taken into custody.

Within a week, he had recovered and was put on trial.

Repercussions

Mangal Pandey had failed in his attempt to provoke his company to revolt, but he would nevertheless become a symbol of martyrdom and spark a rebellion across vast parts of India under the control of the British.

Mangal Pandey was sentenced to death by hanging along with Ishwari Prasad, who was convicted for ordering sepoys not to apprehend Pandey. Pandey was executed on April 8, ten days before the scheduled execution was to take place, in order to curtail the threat of an uprising. Prasad was executed on April 21.

In addition to the executions, seven of the ten companies that made up the 34th Bengal Native Infantry were disbanded in disgrace.

The execution did not have the desired effect the British hoped for. Rebellious sentiment continued to grow throughout the Indian subcontinent, and the colony descended into conflict as the British attempted to restore order. For 18 months, the fighting raged, and hundreds of thousands of lives were lost by the time the British finally managed to claim victory.

Mangal Pandey’s Legacy

Today, Mangal Pandey is seen as a national hero in India, and he is equated with patriotism and the spirit of national pride. His birthday is celebrated every year on July 19. In 1984, the government issued a postage stamp to commemorate Pandey, and a memorial park, Shaheed Mangal Pandey Maha Udyan, was opened in Barrackpore at the place where Pandey committed his famous act and was subsequently hanged.

Mangal Pandey has received significant attention in the media, having been the subject of a 2005 movie and a stage production presented in the same year.

His legacy, of course, is also subject to misinterpretations. It is wrongly assumed that Pandey was a leader in the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny. In reality, he acted alone. Nevertheless, his actions are widely considered, justifiably, the spark that led to the opening of hostilities between the Sepoys and the British. In the war that followed, mutineers were disparagingly named pandies or pandeys by the British troops.

Considered one of India’s first freedom fighters, Mangal Pandey’s fame and influence were largely a result of his death and martyrdom rather than any lengthy struggle against the British. His actions on March 29, 1857, gave the Indian people a sense of confidence and pride and became a defining moment in the rich tapestry of Indian history.