Imagine that you are a merchant in 17th-century Mexico. With bated breath, you stand at the harbor of Acapulco, eagerly awaiting the arrival of enormous treasure ships. Your mouth waters at the thought of the incalculable riches that will soon come ashore. And this event is all the more special because it might only happen once per year.

This is one perspective that contemporaries may have had on the Spanish Manila galleons. For 250 years, these vessels connected four continents in a truly international economy. They carried great riches, but they also embodied the darkest realities of colonialism in the pre-modern world.

What Did the Manila Galleons Carry?

The Manila galleons dominated trade in the Pacific Ocean from 1565 until 1815. During this time, Spain constructed one of the world’s largest colonial empires, both in the Pacific and the Atlantic. To fund their territories and enrich their own country, the kings of Spain financed the first real international economic system. The Manila galleons were directly funded by the Spanish monarchy for this entire period.

According to historians, the actual galleon ships were huge for their time. A typical Spanish Pacific galleon may have weighed one thousand tons, although the largest ships could weigh twice that. As the name “Manila Galleon” suggests, the ships were constructed in and around the city of Manila — the capital of the modern Philippines. From the Philippines, the treasure fleet sailed across the Pacific, destined for the port of Acapulco in Mexico. The journey from Manila to Acapulco took around six months. The voyage back to Asia lasted longer.

The galleons arrived in Acapulco no more than twice per year (usually only once). Each ship carried a dizzying variety of luxury goods in its cargo hold. Some of these goods would be hauled across Mexico before crossing the Atlantic for Europe. Other items would stay in Mexico. Still, other commodities from Europe and Mexico would be loaded onto the Manila galleons for shipment back to East Asia. Let’s explore some of the goods in question now.

Silver

When Europeans first arrived in the Americas, one of their major concerns was locating and exploiting deposits of silver and gold. Silver, in particular, was an essential component of the Spanish colonial economy. This was evident not only in the Americas but in Asia as well.

Imperial China proved to be a major market in the global silver trade. The Chinese had been the first nation to produce paper money centuries earlier, but paper money was not always the most efficient way to pay for goods. The Chinese government didn’t sanction their own, official silver-backed currency, but silver became the de facto monetary standard for China in the 16th century.

The silver trade continued to boom in China for the next two hundred years. The 1600s saw some disruptions due to lower demand and domestic and maritime instability. By the 18th century, however, Chinese silver imports were booming again. The Chinese empire’s demand for Mexican and South American silver seemed unquenchable until the beginning of the 19th century.

Porcelain and Silk

China may have had a huge appetite for American and European silver, but its desire for other foreign goods was much less intense. Other than new foods from the Americas, the Chinese did not need other countries’ goods. After all, the quality of Chinese porcelain and other luxury goods at the time was unrivaled anywhere else on Earth.

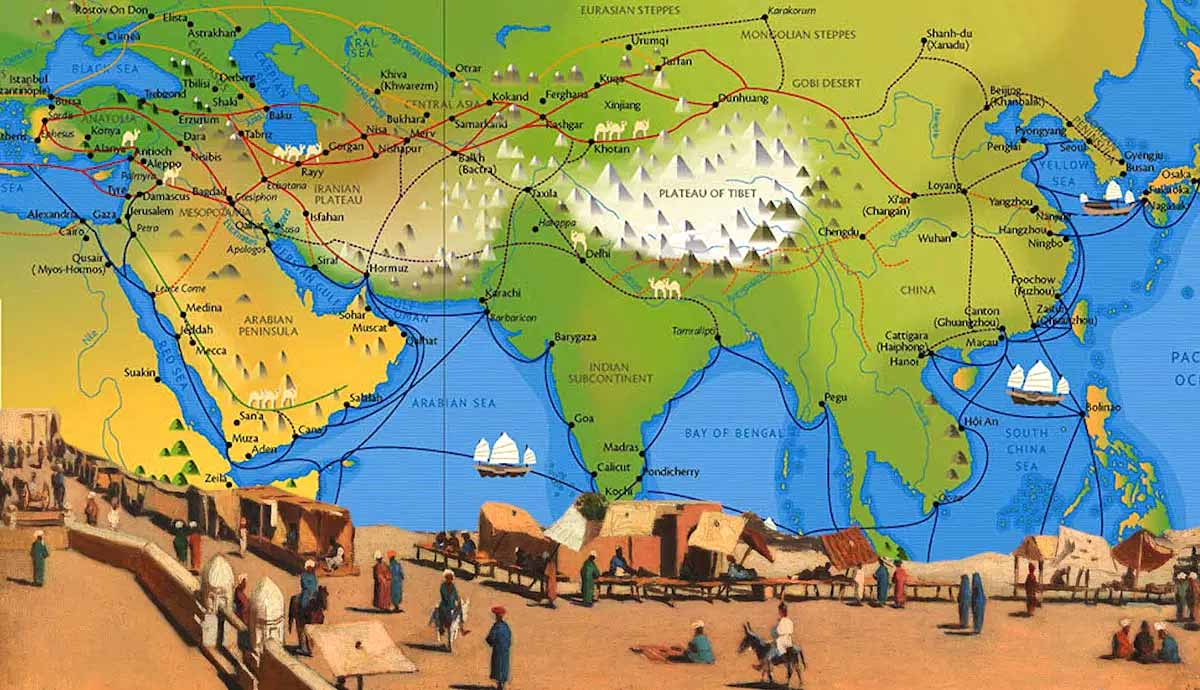

Europe was a different story. European elites craved Chinese goods such as silk and ceramics. The Manila galleon trade allowed the Spanish to gain access to Chinese goods like never before. The silk trade, which had once been the domain of overland exchange, could now happen across oceans for elite consumption. For hundreds of years, European elites reveled in owning Chinese objects, and China developed an international market specifically for the export of porcelain.

Colonial elites in Mexico also developed a taste for Chinese ceramics. Take this 18th-century tureen created for the Mexican market (pictured above). Positioned in the center of the upper lid is the elaborate coat of arms of José de Gálvez, a Spanish nobleman. The fern-like motifs above and below the jar’s lid perfectly illustrate its high-quality craftsmanship, as do the tureen’s gilded handles. Although Chinese-made, this artifact depicts imagery that would have been more appealing to a European or American colonial audience. At the time José de Gálvez acquired this dish, all major European powers were actively trading with Imperial China.

Enslaved People

Now comes the darkest part of the Manila galleon trade. Most readers probably don’t know that there was a trans-Pacific slave trade was born out of European imperialism in Asia. From India to the Philippines and even Japan, Asian peoples who rebelled against Spanish control could be enslaved. Some of them were transported across the Pacific to the Americas aboard the great galleons. Most enslaved Asians in Mexico originated from Southeast Asia, especially the Philippines.

Asians in colonial Mexico lived difficult lives. The surviving documentation tended to categorize all Asians as “Chino/as”; specific ethnic origins were obscured for the most part. However, enslaved Asians were not simply passive vassals of the Spanish monarchy. They actively protested enslavement and economic restrictions through petitions to colonial authorities and even the Crown itself. Some enslaved Asians played with colonial racial terminology to argue against the legality of their condition.

Not all Asians in colonial Mexico were enslaved, however. Some developed small businesses working as barbers and bloodletters. A large crew of Japanese merchants also accompanied the famed diplomat Hasekura Tsunenaga during his journey through Mexico to Spain in 1614. Some of these merchants remained in Mexico and may have even integrated with the Mexican population.

By the mid-18th century, the Manila galleons were crewed by Asian sailors. Historian Diego Javier Luis compiled a register of crew members on one galleon voyage, La Santísima Trinidad y Nuestra Señora del Buen Fin. This galleon was the largest ship in the Spanish fleet to make the trans-Pacific passage. Out of 407 recorded crew members on the ship’s first voyage, Luis identified 224 sailors as having come from Asia. The region of Cavite in the northern Philippines sent the largest number of crew members to sail on the ship’s voyage in 1751.

How Did the Manila Galleon Route End?

The end of the Manila galleon trade coincided with the decline of Spain as a global power. In the early 19th century, the only overseas territory that Spain entirely controlled was the Philippines. Its colonies in North and South America had started to revolt, seeking independence from European domination. Faced with the fracturing of its empire, the Spanish monarchy ceased operation of its treasure fleet. The final Manila galleon ship sailed in 1815. While Spain would hold onto the Philippines for the next eighty years, its American colonies would split away one by one.

Bibliography

Luis, Diego Javier. The First Asians in the Americas: A Transpacific History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2024.