Why is it that the range of debate permitted in mass media is often so limited, even in places which are supposed to be democratic and in which speech is supposed to be free? Why, in fact, are ordinary people so poorly informed in spite of the absence of any formal restrictions on the flow of information? These are the questions pursued by Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman in Manufacturing Consent.

The conclusion they come to is a radical one: that we should consider the Western media as a propagandistic one. This article explains the arguments they pursue as follows: first, a brief note on their collaboration, before focusing on the ‘economic’ incentives for mass media to restrict its reporting. It then moves on the consider the role of unofficial government influence and the effect of public pressure. It concludes with reflections on how Manufacturing Consent turned out to prove so prescient, and how it relates to other elements of Chomsky’s political thought.

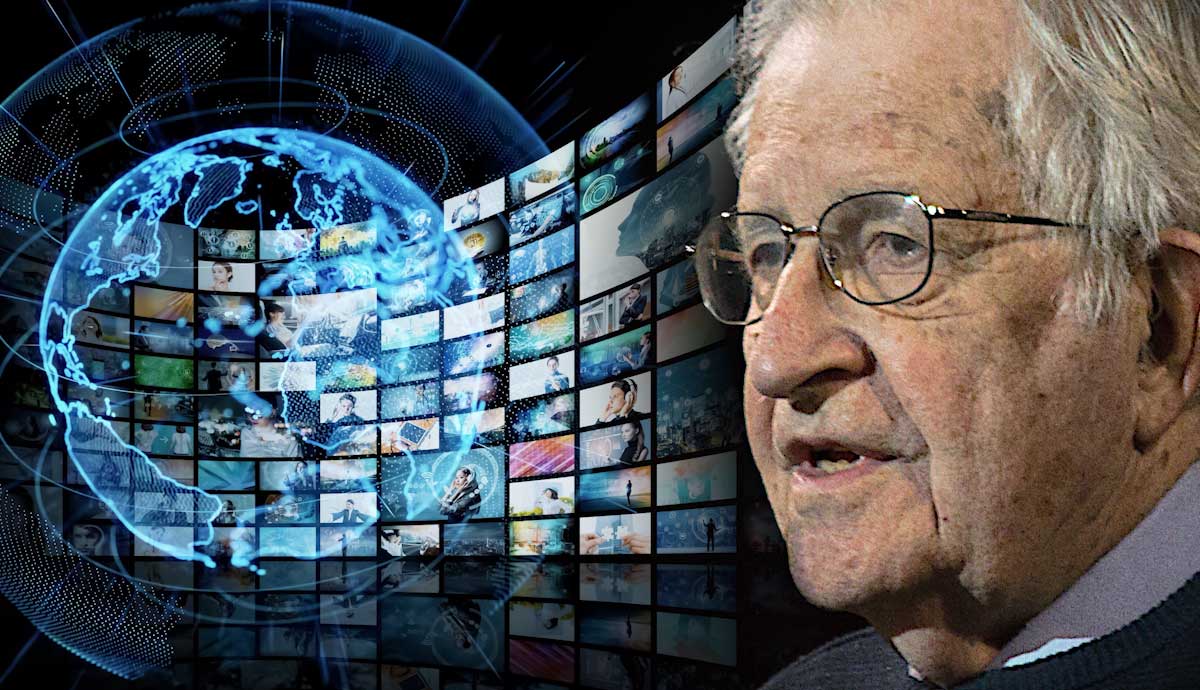

The Authors of Manufacturing Consent: Chomsky and Herman

Noam Chomsky collaborated with media scholar Edward S. Herman to write Manufacturing Consent – presenting the theories contained therein as Chomsky’s is not intended to diminish Herman’s contribution. Indeed, Chomsky has been quite explicit that Herman was arguably the major partner in their collaboration, and that the seeds of many of the core ideas can be found in Herman’s previous work Corporate Control, Corporate Power.

The focus on Chomsky is justified because a large part of what makes Manufacturing Consent so interesting is how it relates to Chomsky’s broader political project, and it is this which will inform some of the conclusions of this article. Undoubtedly, a somewhat different article could be written focusing on Manufacturing Consent in the context of Herman’s authorship at large. This happens not to be that article.

The Basic Premise of Manufacturing Consent

The subtitle of Manufacturing Consent is “the political economy of the mass media.” The attribution of a political economy to mass media is interesting and worth interpreting carefully. One thing we should note is that the term “political economy” has various resonances in the social sciences. The most straightforward definition is simply the study of the relationship between politics and economics. Another definition in circulation is that political economy is the study of the relationship between a government and the citizens whom it governs.

Both definitions seem plausible and apt, given the basic premise of Manufacturing Consent. That premise is simply that the kind of participation which is possible in a democracy (indeed, in any political system which permits some form of participation) is greatly determined by the kind and variety of information about political events that one has access to.

Chomsky and Herman will argue that one of, if not the, most important determining factors behind the kind of information modern-day Americans have access to are the economic pressures placed on major news organizations to report certain things in a certain way.

The Basic Elements: Corporatism

The theory that Chomsky and Herman set out in Manufacturing Consent has come to be called the “propaganda model of communication,” and it has five basic elements.

The first element is “size, ownership, and profit orientation”: this is the argument that, given that the size of large media corporations is based on their profitability, rather than (say) how accurately or fairly their reports are, then the influence of media corporations will be based on their ability to attract investment above anything else.

Second, “the advertising license to do business”: because the largest source of income for news organizations now comes from advertising – rather than, for example, newspaper sales, or some other product of consumer demand – it is the political stance of advertisers that determines the political stance of news agencies and other media organizations. The implication here is that, insofar as a corporation has interests, they are primarily economic. Were the main source of media revenue from individual consumers, that might result in some kind of equilibrium between the political positions held by ordinary people and the issues the news media focus on.

For Chomsky and Herman, the success of a news organization depends greatly on the relationship they are able to foster with governments and large corporations, given the latter constitute a major information source upstream:

“The large bureaucracies of the powerful subsidize the mass media, and gain special access [to the news], by their contribution to reducing the media’s costs of acquiring […] and producing, news. The large entities that provide this subsidy become ‘routine’ news sources and have privileged access to the gates. Non-routine sources must struggle for access, and may be ignored by the arbitrary decision of the gatekeepers”.

The problem, clearly, is the creation of favored or disfavored news sources by these bureaucracies: the very powerful are able to, in effect, decide who should be able to hold them accountable. It would be no surprise if the consequence was less forensic scrutiny.

Another consequence of this, which Chomsky and Herman don’t dwell on but seems obvious, is an intensification of partisanship. Imagine a country that has a left-wing party and a right-wing party. The left-wing party favors its preferred media sources, and the right-wing party favors its preferred media sources, with the best, up-to-date, reliable information. Of course, only one party can be in power and therefore be in a position to supply its preferred news sources with a great deal of useful information. This means that it is a matter of protecting a given news organization’s interests that the political party they align with wins. Clearly, partisanship of some kind is probably inevitable, but it isn’t difficult to imagine a more moderate form of partisanship were the fate of right-wing newspapers bound up in the fate of right-wing parties, and left-wing newspapers left-wing parties.

Catching Flak

Chomsky and Herman also discuss the external pressure media organizations face, as another structural limitation on what media organizations can report or discuss. The arguments addressed so far have been almost exclusively about the distortive effect those in positions of power have. These arguments are pretty intuitive: whatever else one thinks, it is extremely hard to justify a small group of people having a disproportionate degree of control over media organizations.

Things are more complicated when it comes to flak. Chomsky and Herman are quick to suggest that flak can be stirred up by powerful organizations, but clearly, even organic flak – that is, lots of individual readers, watchers, or listeners reacting of their own accord – presents a limitation on the free expression of the press. However, it was previously suggested that part of what was wrong with the disproportionate reliance on advertising was just that it prevented everyone from being able to set the agenda for news organizations – by removing their subscriptions or simply not buying their newspaper at the newsstand. Isn’t this a kind of flak, or functionally similar to it?

It isn’t immediately obvious whether the ideal here should be – whether everyone should be able to put pressure on news organizations, or that nobody should. The latter is difficult to imagine – democratic politics of any kind seems to encourage an extremely vocal expression of opinion. It remains an open question whether flak as such can be eradicated, or merely taken out of the hands of the powerful

Terror and the Rogue State

In the more recent editions of Manufacturing Consent, Chomsky and Herman have added a section addressing the “war on terror” as a mechanism of control. That is, commitment to the war on terror becomes an imperative higher than any particular commitment to fight terrorism, and the insinuation that one isn’t sufficiently on board is so potentially damaging to a news organization’s reputation that it imposes a major restriction on reporting.

This idea is closely related to another element of Chomsky’s broader politics, which he explores in Rogue States. This book is subtitled “The Rule of Force in World Affairs,” and argues that the political culture in the West has stifled the kinds of questions we are able to ask about the motives and intentions of our geopolitical “enemies,” such that we repeatedly misunderstood their behavior with deleterious effects both for people in these places and for people in the West. The idea is that restrictions imposed by the war on terror agenda don’t just prevent good reporting, but they shackle Western people (and thereby Western governments) to ill-informed conceptions of the world and the West’s ability to remake it.

Noam Chomsky Broke the Idealism of the Late 20th Century

One thing worth stressing about this theory and its impact at the time is that the Western world was on the cusp of a period of political self-confidence when this book was published in the late 1980s. Four decades of the Cold War meant that a strong sense of superiority of the Western democratic system of government had been established by contrast with the widespread (and broadly accurate) perception of authoritarianism and corruption in the Eastern Bloc.

From the late 1980s until 9/11, it became plausible – indeed, somewhat fashionable – to hold theories that seem almost insane today, and that glorified the imminent future dominance of Western liberal democracy. What makes Manufacturing Consent so potent is that it argues that information restriction and propaganda, which many Americans and Western Europeans had learned to associate with Communist countries, were, in fact, prevalent in the West too.

In fact, one of the most infamous quotes from the book says exactly that: “Especially where the issues involve substantial U.S. economic and political interests and relationships with friendly or hostile states, the mass media usually function much in the manner of state propaganda agencies.” Moreover, even as Communist regimes began to stutter and fall away, Chomsky and Herman appeared to suggest that this tendency within Western society was liable to get even worse.