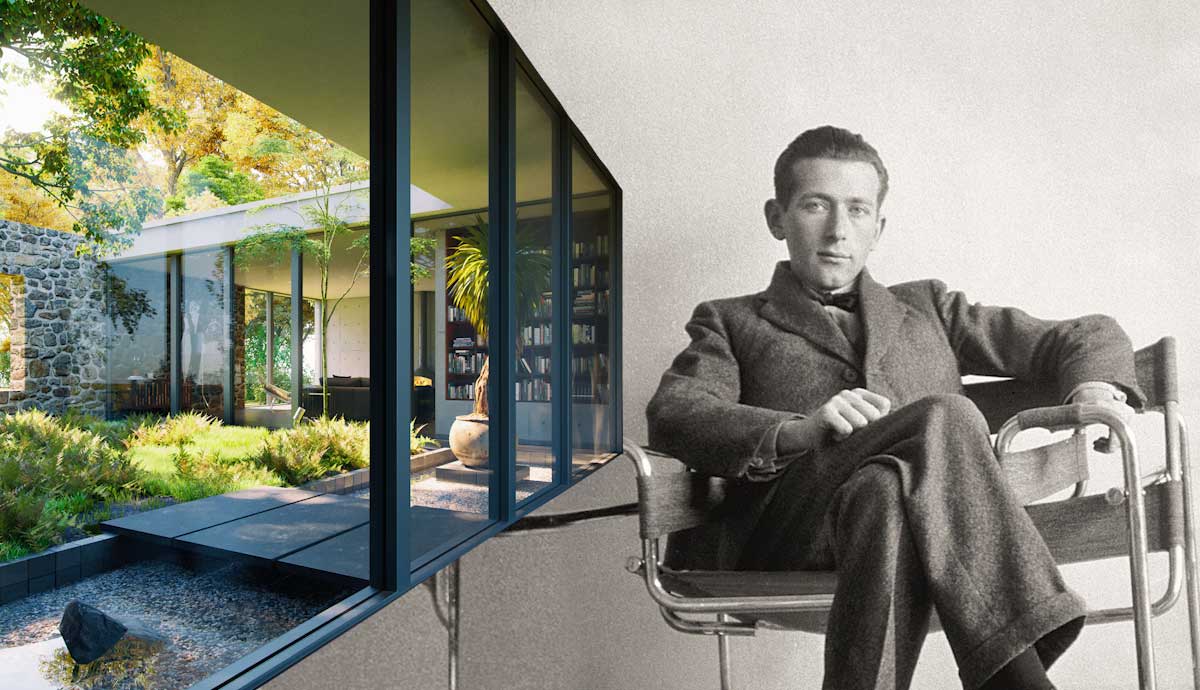

Marcel Breuer became known for his furniture and architectural designs. From the start, he didn’t shy away from experimenting with interesting shapes and materials. As a result, Breuer’s signature style is characterized by clean lines, minimalist forms, and the use of materials such as tubular steel and reinforced concrete. His whole oeuvre embodies the Bauhaus objective of integrating art and industry.

Marcel Breuer’s Early Life

Marcel Lajos Breuer (1902-1981) was born in Pécs, Hungary, as the child of Jakab Breuer and Francisca Leko. Marcel also had two older siblings, called Alexander and Hermina Maria. His friends and family called him Lajkó. Breuer’s father was a dental physician, which allowed his family to live a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. Marcel’s parents were both Jewish, but he himself rejected religion from a young age. Contrary to this, Breuer did embrace another aspect of his upbringing: his parent’s encouragement to take an active interest in culture and the arts.

One of the ways in which Breuer’s parents attempted to raise their children’s awareness of the arts, was by subscribing to various art periodicals. Among these was The Studio, a magazine that covered current developments in both fine and applied arts, as well as architecture. Published in London, the magazine was written in English, a language that the Breuer family didn’t speak or read. Nevertheless, Breuer in particular found the magazine very inspiring and it piqued his interest in becoming an artist himself. At his secondary school, called the Pécsi Allami Forealiskola, Breuer excelled in both the arts and mathematics. Eventually, he graduated summa cume laude and received a scholarship for the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna in 1920.

When Breuer moved to Vienna for his studies, in the late summer of 1920, Europe was still in a state of rebuilding after World War I. With the end of the war in 1918, Austria and Hungary, which had been part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, had become independent nations. It was a time of change that affected various aspects of society. Against this backdrop, the young and talented Breuer arrived in Vienna to start a new phase of life. However, he withdrew from the Academy soon after starting classes. He felt that the classes focussed too much on discussions about aesthetic theories, rather than on the fundamentals of drawing, painting, and sculpting. Instead, Breuer took an apprenticeship in the shop of a local cabinet maker called Bolek. Soon, he found out about the Bauhaus School of Design, Building and Craftsmanship in Weimar.

Marcel Breuer at the Bauhaus

Only a few weeks after Breuer learned about the Bauhaus, he managed to secure a place there among 143 other students. The Bauhaus was founded only a year earlier, in 1919, which meant that Breuer went there during its early days. Throughout Breuer’s four-year study at the Bauhaus, he mainly devoted himself to studying architecture. There were no official architecture classes yet during the first years of the Bauhaus, instead, Breuer gained architectural training during an apprenticeship under Walter Gropius. After following a carpentry workshop under Gropius’ leadership, they became close. Another important source of inspiration came from his painting teacher Paul Klee. Klee’s visions of painting inspired Breuer. Klee taught him that a painting was built up in the same way as an architectural structure with repetitive, geometric units.

After completing his studies at the Bauhaus in 1924, Breuer spent a short while in Paris, where he worked at the office of Pierre Charreau. He was soon asked to return to Weimar as the Bauhaus head of the furniture and carpentry workshop. When the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau the following year, Breuer got involved in the interior design plan for the new school.

In 1926 he established the Standard Möbel Company, through which he started marketing a full line of steel furniture. He also got married to Marta Erps, who was studying weaving at the Bauhaus workshops. Breuer and Erps met each other while collaborating on the Dessau project. However, their relationship only lasted a few years and they officially divorced in 1934.

Towards the end of the 1920s, the Bauhaus dealt with some internal political issues, as well as the increasing pressure from Germany’s rising Nazi regime. As a result, many people left the Bauhaus, including Gropius who was the school’s director at the time. Breuer himself left. He went to Berlin, where he joined the Bund Deutscher Architekten and founded an architectural practice with a former student. During the late 1920s, Breuer first worked on small commissions. His work was represented at various exhibitions. In 1932, he received his first independent architectural commission for a modern house.

Following the completion of this project, Breuer traveled extensively through Southern Europe and Northern Africa. It was a time of exploration, which unfortunately ended with his return to a grim Germany. The disturbing political atmosphere made Breuer move in the end. With the help of Gropius, he secured papers to relocate to London, where he, as a Jewish citizen and modern artist, would be safer. After all, Nazi supporters thought that modern art and architecture were the art of decay. They even organized an exhibition called Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) in 1937. In London, Breuer independently developed a line of bent plywood furniture.

Breuer’s move to the United States

Because of limited building prospects in England and increasing war threats, Breuer decided to move once again in 1937. This time, his destination was the United States, where Gropius secured him a position at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Just like other Bauhaus immigrants, Breuer was drawn to the structural transparency and efficient design of American industrial buildings and inspired by the traditional architecture of America’s New England region.

Filled with new inspiration, Breuer and Gropius formed a partnership and produced several iconic houses together. Starting from the mid-1940s, Breuer established his own practice, initially in Cambridge and later in New York, where he relocated to in 1946. In 1940, he got married to his second wife Constance Crocker Leighton, better known as Connie. Connie, who had studied at the Brimmer School, would work as his secretary, business manager, and accountant. Together they had two children, Tamás and Francesca.

Breuer designed several iconic homes, which formed the pinnacle of his domestic architectural production. Thanks to the success of these projects, he received international recognition during the 1950s as one the key figures of modern architectural design. He was now seen as one of the great architects like Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Breuer would also design many important public buildings, like the UNESCO headquarters in Paris and the Bijenkorf department store in Rotterdam. However, he wouldn’t do all of his projects by himself. In 1956, Breuer formed a partnership with several young architects who had worked for him, operating as Marcel Breuer and Associates. Together they designed impressive and diverse works like the Armstrong Rubber Building and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. By the mid-sixties, Breuer had settled in his office at 635 Madison Avenue in New York and opened an office in Paris as well. Breuer’s studio produced over a hundred buildings.

Years of hard work eventually took their toll. During a trip to Afghanistan, Breuer suffered from a nearly fatal heart attack after which he was forced to slow down and take a step back from the central role in his company. However, regardless of his weakened health and the difficult economic climate of that period, Breuer continued to design buildings all throughout the 1970s. During this last decade of Breuer’s life, he also received a number of honors. Exhibitions of his works were held at the Bauhaus-Archiv Museum in 1975 and at the MoMA in 1981. Breuer passed away on July 1, 1981, having reached the status of an architectural genius.

The Wassily and Cesca Chair

During Breuer’s second period at the Bauhaus, from 1925 to 1928, he started to experiment with bent tubular steel furniture. The first version of the iconic B3 chair was developed in 1925. The chair would later be called the Wassily Chair, after the artist Wassily Kandinsky who was Breuer’s friend and fellow Bauhaus instructor. The chair is made out of a tubular steel frame and leather panels. Breuer called it his most extreme work, the least artistic, the most logical, the least cozy, and the most mechanical.

When coming up with the chair he was inspired by the tubular steel handlebars of his bicycle. These were strong, lightweight, and mass-produced. The steel on bike handlebars is normally bent, so Breuer wanted the steel to bend in many more shapes in his furniture pieces. The Wassily Chair is a prime example of modernist design which focused on functionality, minimalism, and the use of new materials and new manufacturing techniques. The Wassily Chair was made out of a small number of parts by using new techniques like welding.

Shortly after finishing the Wassily Chair, Breuer continued experimenting with tubular steel. This resulted in his design of B32, also known as the Cesca chair. This chair is made out of a single tubular steel frame and two wooden frames with webbing used for the seat and the backrest. Through the use of these materials, Breuer combined mass-produced steel and handwoven jute webbing, thereby integrating the industrial realm with crafts. B32 was another great example of modernist design. It was in fact the first ever cantilever chair. The chair was also named the Cesca chair after Breuer’s daughter. This name was first suggested to Breuer by the Italian manufacturer Dino Gavina, whose firm began making both the Cesca and the Wassily chair during the 1950s.

Hooper House

The Hooper House, also known as the Hooper House II, was the second house that Marcel Breuer designed for the wealthy philanthropist Edith Hooper and her husband. For this project, Breuer collaborated with his associate Herbert Beckhardt. The construction of the building began in 1958 and it was completed a year later. The Hooper house, which is built in Baltimore, has a single-storey and a binuclear design. The house is divided into two wings. One wing consists of living, kitchen, and dining areas, while the other one features a sleeping area. The Hooper House also has divided areas for children. Breuer himself said: You want to live with your children, but you also want to be free from them, and they want to be free from you.

Thanks to the open plan, many windows, and the inner courtyard it’s still possible for residents to feel connected to each other. In other words, the layout of the rooms doesn’t strictly imply separation. Apart from being connected to one another, the Hooper House also allowed its residents to stay connected with the surrounding nature. The residents had a great view of the forest and Lake Roland in the East. With its Maryland fieldstone façade on the west and many glass walls, the building itself blends in with the forest around it. Thanks to the use of steel and glass, the Hooper House is considered a great example of modernist architecture.

Gagarin House I

In 1956, Breuer designed the Gagarin House I for Andrew and Jamie Gagarin. The house, which was built in Litchfield, Connecticut, features a steel frame and reinforced concrete structure. On the outside, the structure is made out of the same Maryland fieldstones as the Hooper House. There are also many glass walls. Thanks to this, the Gagarin House I seems very light and provides a great view of the land around it. The house also has a long terrace and a pool area. Outside, one can find Breuer’s signature metal railing and floating stairs. Just as in his design of the Cesca chair, Breuer made use of strong steel when creating these seemingly floating and lightweight stairs.

For the interior, Breuer used a variety of materials like wood, concrete, and brick. Children’s bedrooms and playrooms were designed to be on the lower floor, along with storage rooms, while the upper floor featured additional rooms and the master bedroom. In this design, Breuer again chose to separate the children’s rooms from the space dedicated to adults.

The Whitney Museum of American Art

Breuer designed a new building for the Whitney Museum of American Art on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The building, also known as The Breuer Building or 945 Madison Avenue, consists of a massive structure. For the exterior, Breuer used reinforced concrete, as well as grey-colored granite cladding. The use of these materials made the Whitney Museum stand out from nearby buildings made with traditional limestone, brownstone, and brick. Thanks to its shape, as well as the use of concrete and granite, the Breuer Building was considered somber and heavy at the time of its completion. However, it is now viewed as strong, daring, and innovative.

The first floor consists of a lobby, coat room, small gallery, and loading dock. The second, third, and fourth floors were dedicated to gallery space, each progressively larger than the space beneath it. Finally, the fifth floor consisted of administrative offices, while the sixth floor held a large mechanical penthouse. The interior is made out of terrazzo (a composite material of marble chippings set into cement), board-formed and bush-hammered concrete, bluestone floors, and walnut parquet. Many of the ceilings of the exhibition spaces were coffered, giving the spaces an interesting sense of depth. With the absence of daylight in the exhibition spaces and the use of heavy materials, Breuer aimed to give the Whitney Museum the feeling of a sanctuary for modern art.

After 48 years, The Whitney Museum of American Art moved out of the Breuer Building in 2014. After this, the building functioned as a part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art called the MET Breuer. However, the MET Breuer was in the Breuer Building from 2016 to 2020. In the period from March 2021 until the end of 2023, the building will function as the Frick Madison, a temporary Gallery of the Frick Collection.

The Armstrong Rubber Company or Hotel Marcel

The Armstrong Rubber Company, also known as the Pirelli Tire Building, was one of Marcel Breuer’s most significant architectural projects in the United States. The building was commissioned by the Armstrong Rubber Company in 1966, after which Breuer started working on its design. Eventually, he came up with a design that is now a key example of Brutalist architecture. Breuer used reinforced concrete as his main material here. The Pirelli Tire Building was one of the first buildings where the floor framing was suspended from the overhead cantilever trusses. Each of the fifty-ton trusses supports the steel frame blocks below them. What makes the structure remarkable is the fact that it looks both heavy and light at the same time. The opening in the middle also gives the structure a sense of lightness.

In 1988, the Pirelli Tire Company bought the building and briefly used it as its North American headquarters, before leaving it unoccupied for a few years. In 2003, the Swedish furniture manufacturer IKEA purchased the site and announced plans to build an adjacent store. To be able to receive their future customers, they decided that a section of the former Armstrong Rubber Company would be demolished, to make room for a new parking lot. Regardless of the criticism that these plans received from the Long Wharf Advocacy Group, as well as the American Institute of Architects, IKEA continued with its initial plan. As a result, most of the low-rise sections of the structure were demolished.

In 2019, the building was bought from IKEA by the architecture studio Becker & Becker. Fortunately, the building is now in good hands. Bruce Becker even said that brutalist buildings like the Pirelli Building are works of art that can inspire and elevate the quality of meaning of our daily lives. Becker & Becker repaired the original façade and transformed the interior into a hotel with 165 rooms. In May 2022, the Armstrong Rubber Company was officially reopened as Hotel Marcel under the Tapestry collection of the Hilton Hotels. The hotel is also the first NET-Zero Energy hotel in the United States. This means that more than one thousand solar panels give power to Breuer’s building.