When we think of the world of discovery, we often think of explorers and pioneers with a certain sense of romance. Their transmission into readable accounts is what reaches us, the readers of those marvelous stories. Their discoveries, therefore, were transformed into the texts we know today. Marco Polo would strike us as one of those explorers or pioneers who shaped the travel literature genre into what it became later.

Other writers, however, made their mark with their literary endeavors with quite a different approach. This is the case of Sir John Mandeville or, much later, Niccolao Manucci. Mandeville was a contemporary of Polo, and both traveled the Far East. Both men brought great literary accounts of their journeys. Their approach, however, was radically different when presenting their work to their readers. Exploring their Travels, their editions, and their reception by the public is key to understanding the early development of travel writing literature.

The Life & Achievements of Marco Polo

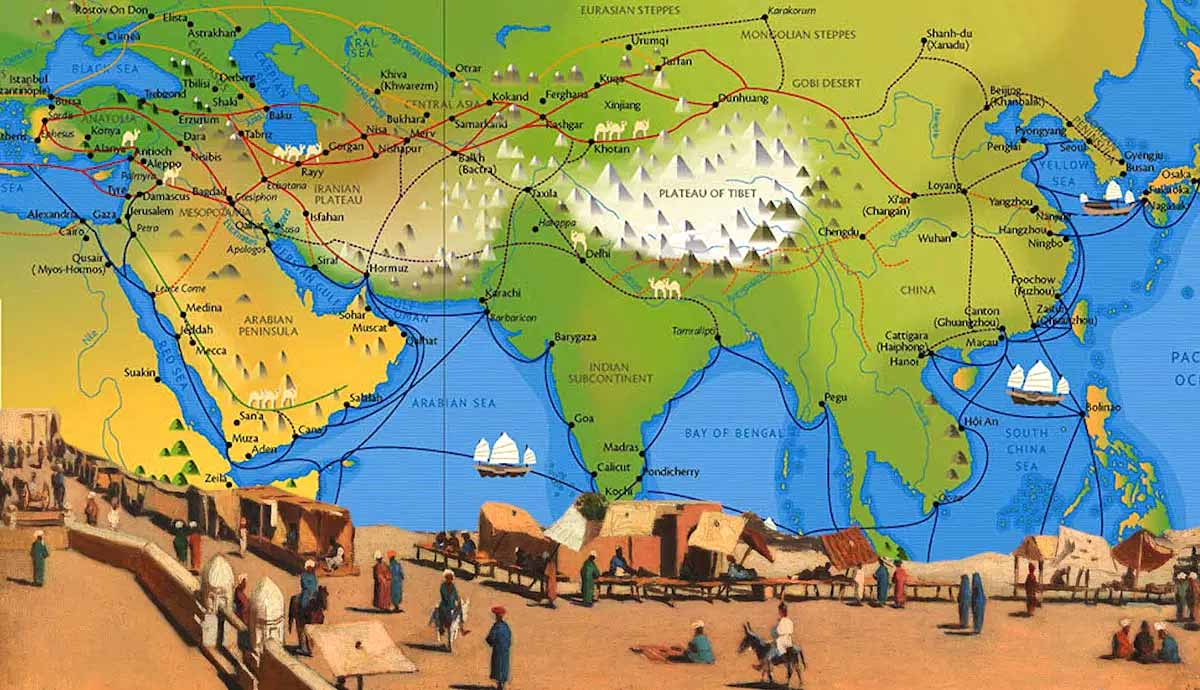

Marco Polo spent much of his adult life traveling the Far East at the service of the Mongol Empire. It was not entirely uncommon for other European travelers who traded along the Silk Road to know some of these realms. In this fashion, the Polo family traveled the Far East, and from about 1260, young Marco began his journey to China.

There, he spent several years serving the Mongol Empire. On his return, he arrived in Venice in 1296, where he was captured by the Genoese. Polo wrote his Travels, an account of his journeys through Asia. He owes this feat, in part at least, to a Genoese, Rustichello da Pisa, whom he met while in captivity. Da Pisa knew the literary trends of the time in Europe. The resulting tales might have been as foreign and awe-inspiring to his readers as tales of magical and romantic travel literature. Wonderments and imagery such as those were regularly consumed by the readers of the day.

Regardless of both men’s intentions, Travels cannot be considered a travel book, or at least not as it was conceived. Polo presented a nonchalant work of human geography, which did not attract the common reader in their thirst for enjoyment. His literary endeavors dealt greatly with the political compositions and the description of the peoples under Mongol-controlled territory. Due to the extensive nature of the content, Polo seems to touch only superficially on geography and never on art or architecture.

His description of the marvels he encounters is matter-of-fact, without flairs in his language or exaggeration. He described physical geography only sporadically and superficially; his focus was the description of peoples, customs, and governments in China and Southeast Asia. To complement this content, his style was as prosaic and concise. The book was first published circa 1300 in French but not translated into English until 1579.

Sir John Mandeville: A Different Approach from Marco Polo

Sir John Mandeville was a near-contemporary of Marco Polo. Mandeville likewise traveled the Far East and brought back an extraordinary compilation of tales. His travels through China revealed to his readers fantastic and dream-like creatures, lands of hitherto unseen riches, and peoples with supernatural qualities. It may seem now ludicrous to think the literate classes of late medieval communities could take such descriptions at face value.

However, the realms written about in his work had never been seen nor described by anyone with whom the readers could hope to meet or familiarize themselves. Incidentally, the identity of Sir John Mandeville is disputed by scholars — Jan de Lange, a French abbot, appears a plausible but highly disputed candidate: he has been cited as publisher and patron of this and other works of travel literature of the time, and has been identified as the author behind the pseudonym of John Mandeville.

Notwithstanding the authorship mystery, Mandeville’s was the more attractive of the two writings compared with Polo’s Travels and was conformant with popular literary trends. Indeed, Polo’s fell into near oblivion victim to literary fashions of fantasy prose of the time. Mandeville’s work was translated into numerous European languages and enjoyed great popularity from his first publication in 1356. Mandeville’s writing provided the readers with a much more familiar literary genre that European consumers craved.

According to the literary trends of the time, his depiction was a work of romantic fantasy travel; it presents itself clearly as fiction without ever openly admitting to it, making the reader a tacit accomplice to the mischief. Mandeville enjoyed great success in his lifetime with readers across Europe; his name surely became part of many households’ daily conversations.

Marco Polo’s Travels was First Shunned by Readers but Aged into a Timeless Work

As previously mentioned, Marco Polo enjoyed little success compared to Mandeville. His Travels were nonetheless considered a work of value for the intellectually literate classes. In his partnership with his Genoese acquaintance, Polo tried to adapt the work to the literary trends of the times. But the result is a prosaic, nonchalant narrative of foreign geography. It has precise descriptions of the places he visited, the peoples and their customs, and the governments under which they were ruled. It is a conscientious work of human geography. Such descriptions from hitherto unexplored places resulted from a feat many considered treasured knowledge.

Polo’s attempts were enlightened and exhaustive. He named the unseen with a similar keenness as Mandeville did; that is to say, he endowed his Travels with as many unlikely scenes as he could note. An example of this is found in the text itself:

“They have wild elephants, and great numbers of unicorns, hardly smaller than elephants in size. Their hair is like that of a buffalo, and their feet [are] like those of an elephant”

(Marco Polo’s On Unicorns and Pygmies (Kingdom of Basman) Benedetto, ed. The Travels of Marco Polo, Taylor & Francis Group, 2004).

It would have been difficult to fathom such a creature in the kingdom Animalia if one had never seen or heard about the Indonesian rhinoceros. Polo, conversely, continues to write some descriptions as factual and evidence-driven revelations, such as: “I also wish you to know that the pygmies that some travelers assert they bring from India, are a great lie and cheat […]” (Ibid). It could seem that these last quotes, extracted from the same excerpt from the main text, produce an amusing dichotomy, particularly in the way Polo presents his findings.

Marco Polo’s Travels Contributed to the Creation of Travel Literature as a Genre

For those whimsical descriptions and characterizations (and surely for other reasons), Marco Polo’s Travels was initially dismissed as a charade of half-imagined tales. It was not until many years later that an attempt was made to bring the work into the broader literary market. The reexamination of the piece marked a new starting point in the literary traditions of later times. In considering the term “work of human geography” to describe his work, we ought to acknowledge that this refers to its historical context; that is, this is how Polo’s contemporaries would have categorized the work. Furthermore, without neglecting at least some of said context, we cannot categorize the Travels as anything other than a work of “human geography.”

When later editors and readers took a keen interest in Marco Polo’s writings, they not only reintroduced the work but expanded the literary culture of the time; Marco Polo’s Travels created a new literary genre within an existing literary genre: subsequent generations, through Marco Polo, reinvented the literature of “Travel Writing.”

It is indeed challenging to trace the evolution of the literature from those remote ages. If the authorship of The Travels of Sir John Mandeville is still unresolved, equally, we cannot hope to adjudicate merit to Polo for his contribution to world literature. Nevertheless, we still can enjoy his endeavors with a fascination for the Late Medieval reader, who, far from being dismissed as a byproduct of editorial practices, should be commended for his inventiveness and imagination in lieu of experience or learning.

War, Disease, & Boredom: The Perfect Recipe for Fantasy Literature

It is worth noting that the European world desperately needed such kinds of literature. The writings from both men were a welcome distraction from war, epidemics, and perhaps the dullness of daily life for some. As mentioned above, Mandeville was to be very successful in entertaining the readership, and, for a long time, his writing was the preferred work and, by much, the more popular of the two. Also, his depiction of the marvels he encountered was, without a doubt, part of his formula for success.

The European population had been for some time engaged or dragged into the Hundred Years’ War, and the recent and recurrent epidemics of several deadly diseases were making a dent in the little sense of security and stability of many. Indeed, life in Europe at the time had very little to offer in the sense of enjoyment outside the material world if one were lucky enough. For most, the pleasures of mundane activities were as much as they could aspire to.

The Travels of Polo & Mandeville: the Tangible & the Phenomenal

While the works of both Mandeville and Polo have survived into our days as historical artifacts and as part of the intellectual history of Late Medieval Europe, we can clearly discern the work with the most weight has had in history is the most memorable one. Indeed, The Travels of Marco Polo have shown a resilience that few other pieces of literature have. However, the reason can be twofold: an eager eye for the facts that lay beyond the borders known to the European people and sheer ineptitude when approaching the literary market — Polo’s commercial mistake unintentionally helped him slide into the best-known names in History.

Mandeville, on the other hand, has enjoyed the opposite fate. While his work succeeded in meeting the needs of the readers it was intended for, his fantastic creatures and colorful lands have faded from our memory, and his work has become a historical anecdote; his books, historical artifacts: and they probably are so for several centuries now. Both works have unequivocal merits and value; they seem to have, however, crossed paths along their respective histories.