Margaret Cavendish was an exceptional case of a female philosopher and intellectual in the 17th century, an era when women were still considered inferior and incapable of philosophical and scientific reasoning. Although she never had a systematic scientific or classical education, she managed to obtain adequate scientific knowledge to articulate a personal naturalistic theory opposed to the popular and robust Cartesian dualism and to write one of the first science fiction novels.

The Early Life of Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish (1623-73) grew up during the English Civil War and at the beginnings of the Enlightenment, a very turbulent and exciting period of European history. Charles I of England had been on the throne of England since 1625; an arrogant and conservative king who couldn’t get along with landowners, the class that had been starting to gain power and wealth since the Renaissance.

As a fanatic Catholic, Charles had abolished the Protestantism established over a century before by Henry VIII, a cruel king known for his brutality and numerous women. Charles not only returned to Catholicism, but he also married a Catholic French noblewoman named Henrietta Maria. However, he did not do well as a ruler. He was arrogant and indifferent, if not aggressive, towards Parliamentary decisions, believing that “democracy is the power of equal votes for unequal minds.” As Parliament consisted mainly of noble landowners who had just begun to perceive their power, the King lost their financial support in 1629, when he dissolved the parliament.

The country could not survive without the contributions of the nobles. The English people went hungry for more than ten years, and Charles, not wanting to be deprived of his luxuries, was obliged to reconvene the Parliament in 1640. The new Parliament was openly hostile to the King, and the Scots insisted on its adopting Protestantism. This culminated in the first English Civil War of 1642, fought between the Parliamentarians and the Royalists.

Formative Years and Marriage

Margaret Cavendish was born as Margaret Lucas in 1623 in Colchester, England. She was the eighth child of a prominent aristocratic and staunchly royalist family. After losing her father at the age of two, she was raised by her mother. She didn’t have a systematic education as a child. However, as her two older brothers Sir George Lucas and Sir Charles Lucas were scholars, Margaret, from a very young age, had the privilege of having conversations about scientific and philosophical issues that gradually inspired her to formulate her own views. Besides writing, she loved to design her own clothes.

In 1643, she entered the court of Queen Henrietta Maria and became a maid of honour. As the Civil War broke out, she followed the Queen to France. It was a wise decision despite the difficulty of leaving her home environment’s safety, as Margaret’s royalist family was not well-liked by the community.

Margaret was shy and thus didn’t have a good time in the French court. In 1645, she met William Cavendish, a famous royalist general who was then in exile. Although he was 30 years older than herself, they fell in love and got married. William Cavendish, Marquis of Newcastle was a cultivated man, a patron of the arts and sciences and a personal friend of several notable scholars of the day, including the philosopher Thomas Hobbes. As a writer he admired and respected Margaret’s spirit and eagerness for knowledge, encouraging her to write while supporting her books’ publication. Despite her famously bitter comments about marriage (“Marriage is a curse we find, especially to womankind,” and “Marriage is the grave or tomb of wit”), Cavendish had a good marriage and a husband utterly devoted to her. She never stopped honouring him, and even wrote his biography.

A Female Philosopher in 17th-Century Society

According to The Laws and Resolutions of Women’s Rights (by the assigns of John More, 1632), the earliest book in English on the legal status and rights of women, women lost their legal status after marriage. By the common law of coverture, wives were not legally autonomous persons and could not control their own property. Single women, or femes soles, had considerably more property rights. However, they were marginalised and received consistently less favourable treatment than wives or widows, especially in terms of access to poor-relief and permission to run their own commercial enterprises.

In fact, women in 17th century Europe were an ambivalent issue. On the one hand, there was a broad contempt toward the female subject as a “needful evil.” On the other hand, there was an exhaustive discussion on the nature of woman, a broad conversation on her ability to study and the praise of an archetype female figure representing beauty and grace. This ideal woman, in order to restrict her natural susceptibility to evil, should be constrained, silent, obedient and continually occupied so as to avoid any free time that would lead her to corruption. Besides, a woman should not be educated as, since an educated woman was prone to being dangerous because of her weak morality.

With very few exceptions, like Artemisia Gentileschi or Aphra Behn, a woman’s will to be educated and creative, to write and articulate personal reasoning, and even more to be a female philosopher was daring, and was mostly met with contempt and ridicule.

In sum, women in the 17th century were second-class citizens. The rise of the puritans during Cromwell’s republic had a dramatic impact on these premises.

Poems, Philosophy, and Fancies

In 1649 Charles was tried for high treason, eventually becoming the first king to be beheaded in British history. During the following years of Oliver Cromwell’s republic, Margaret and her husband travelled around Europe where she studied politics, philosophy, literature, and science more systematically. With William’s continuous support, she wrote a lot, and in 1653 she published her first two books, Poems, and Fancies (1653) and Philosophical Fancies (1653). In the next twenty years and right up to her death, Margaret Cavendish was prolific, publishing more than 20 books.

With the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, the couple returned to England and retired to William’s estate at Welbeck. Margaret there continued her writing while publishing what she had worked on during her travels.

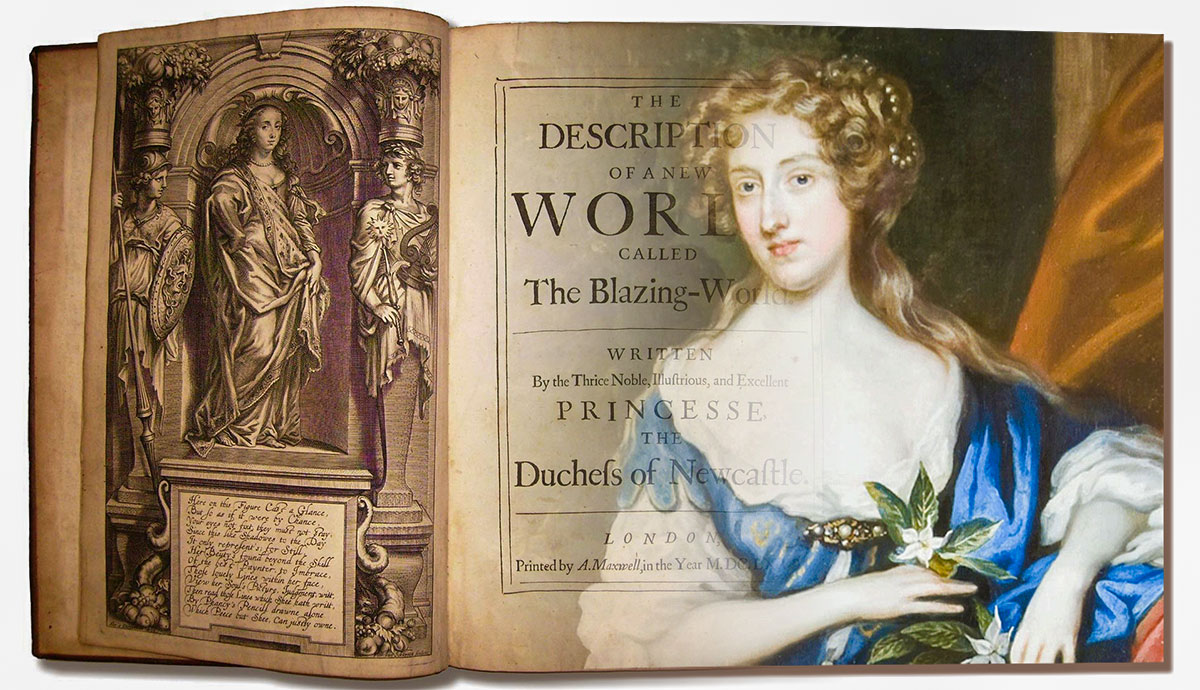

Margaret wrote and published under her name, a courageous action in an epoch where most women who published their writing preferred to do so with pseudonyms. When in England, she discusses the scientific and philosophical ideas of her time’s great minds, such as Thomas Hobbes, Robert Boyle and Rene Descartes. Her unique personal contemplations are expressed through poems, plays, essays and imaginary correspondences. Among them, a novel, The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World (1666), better known as The Blazing World, was one of the first science fiction novels of all time.

The Lady Contemplates

Margaret Cavendish’s philosophical thinking was ahead of its time. Openly and bravely anti-cartesian in a cartesian era (named after philosopher René Descartes), she saw the natural world as a whole wherein the human being is equally important with all other creatures. She even accused humankind of cruelty against nature. Her anti-anthropocentric and egalitarian stance towards the natural world may seem surprising for the period, especially for a staunch royal supporter; however, Cavendish’s absolute monarch was not God, but Nature (“Monarchess over all creatures”), an impressively postmodern idea.

Her philosophy can be seen as an early version of naturalism. She believed in the intelligence of matter and considered the mind inseparable from the body. She denied the platonic theory of forms along with the mechanistic outlook, assuming that ideas are located in the mind and believing in an unpredictable, advancing nature. Thus, she argued for a body that was continually evolving, and a mind-interacting system that shares similarities with Simon de Beauvoir’s ‘body as a situation.’

Her materialism seems inspired by Thomas Hobbes’ philosophy and sometimes foresees John Lockes’ empiricism. By suggesting that the mind is rooted in the body, she implies that the ideas we detect and know are a part of nature and hence are material-based. Cavendish believes in a “self-knowing, self-living, and perceptive” nature that, through these qualities, keeps her own order, avoiding chaos and confusion. It is an idea reminiscent of Bergsonian elan vital, and given that she attributes intelligence to non-living matter, her vitalism could even be interpreted in a Deleuzian way.

Margaret Cavendish discussed gender roles and male and female nature through her writing, albeit in somewhat contradictory ways. In some texts she held positions about the inferiority of women in spiritual strength and intelligence, while in others, as in her “Female Orations,” she presented arguments that could be characterised as proto-feminist. In fact, she regarded women’s inferiority as not natural, but the result of the lack of education of women. She argued that keeping women outside education was a deliberate decision, made by certain social institutions in order to keep them under subjugation.

However, although critical towards women’s treatment by men, she didn’t believe that men and women have equal capacities. She often persisted in seeing some feminine traits as essential and natural (which she occasionally feels guilty to have trespassed). In any case, she kept believing in personal freedom, and that anyone should be whatever she chooses to be, even if this contradicts social norms. In this respect, too, she can be considered proto-feminist.

Mad Madge

It was challenging to be accepted as a female philosopher in the 17th century (as Cavendish’s biographer, Katie Whitaker, observes, in the first forty years of the 17th century only 0.5% of all published books had been written by women). Margaret Cavendish was an eccentric woman, determined to be heard. Yet she was fairly socially inept, often unable to meet the standards of courtly manners. She had an incredibly sophisticated taste in clothes, and used to wear men’s clothes, an act which provoked bitter comments (Samuel Pepys commented in his diaries about her “unordinary” deportment). Yet, she talked about things that other women didn’t dare talk about, and she was one of the few female philosophers to argue against Descartes.

Thus, she became known as Mad Madge (especially by later writers), was mocked for what she wore as well as for her ideas and writing. Royal diarist and Royal Society member Samuel Pepys refuted her ideas, and John Evelyn, also a member of the Society, criticised her scientific thought. Other contemporary female philosophers and intellectuals, such as Dorothy Osborne, made scornful and insulting remarks on her work and manners. While there was a fair number of admirers of her work, among others the proto-feminist and polymath Bathsua Makin, Margaret Cavendish wasn’t taken seriously by literary historians for many years after her death in 1673.

Margaret Cavendish’s legacy

The general ambivalence towards Margaret Cavendish’s writing also has its roots in Virginia Woolf. The latter not only wrote about the Duchess in A Room of One’s Own (1929), but she had already dedicated an article to her in the Common Reader (1925).

In the former work, Woolf investigated the reasons for female hesitancy towards writing. Using Cavendish as a counterexample, a bogey to frighten clever girls, Woolf ends up in her unfair judgement of the female philosopher. Woolf mocked her as follows: “What a vision of loneliness and riot the thought of Margaret Cavendish brings to mind! as if some giant cucumber had spread itself over all the roses and carnations in the garden and choked them to death.” Some years before, Woolf’s criticism was far tenderer, yet still cruel: “There is something noble and Quixotic and high-spirited, as well as crack-brained and bird-witted, about her. Her simplicity is so open; her intelligence so active; her sympathy with fairies and animals so true and tender. She has the freakishness of an elf, the irresponsibility of some non-human creature, its heartlessness, and its charm.”

Was Woolf influenced by the scorn of Cavendish’s critics, or was her taste just not attuned with the duchess’s extravagant style? Either way, she finally admitted the duchess’s potential: “She should have had a microscope put in her hand. She should have been taught to look at the stars and reason scientifically. Her wits were turned with solitude and freedom. No one checked her. No one taught her.”

Today Margaret Cavendish’s legacy seems to have been recovered. The International Margaret Cavendish Society is an institution dedicated to increasing awareness of her life and work. In addition, several articles, books, and theses have been written in the last few decades which explore her life, her philosophy, and unique thought.