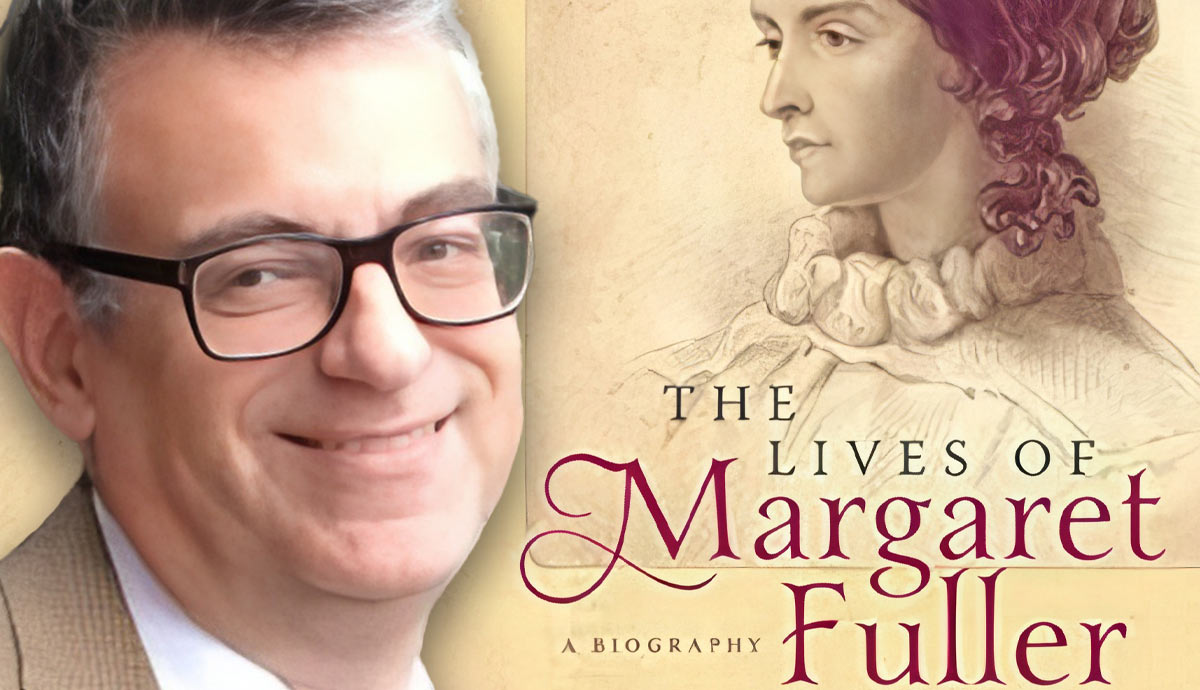

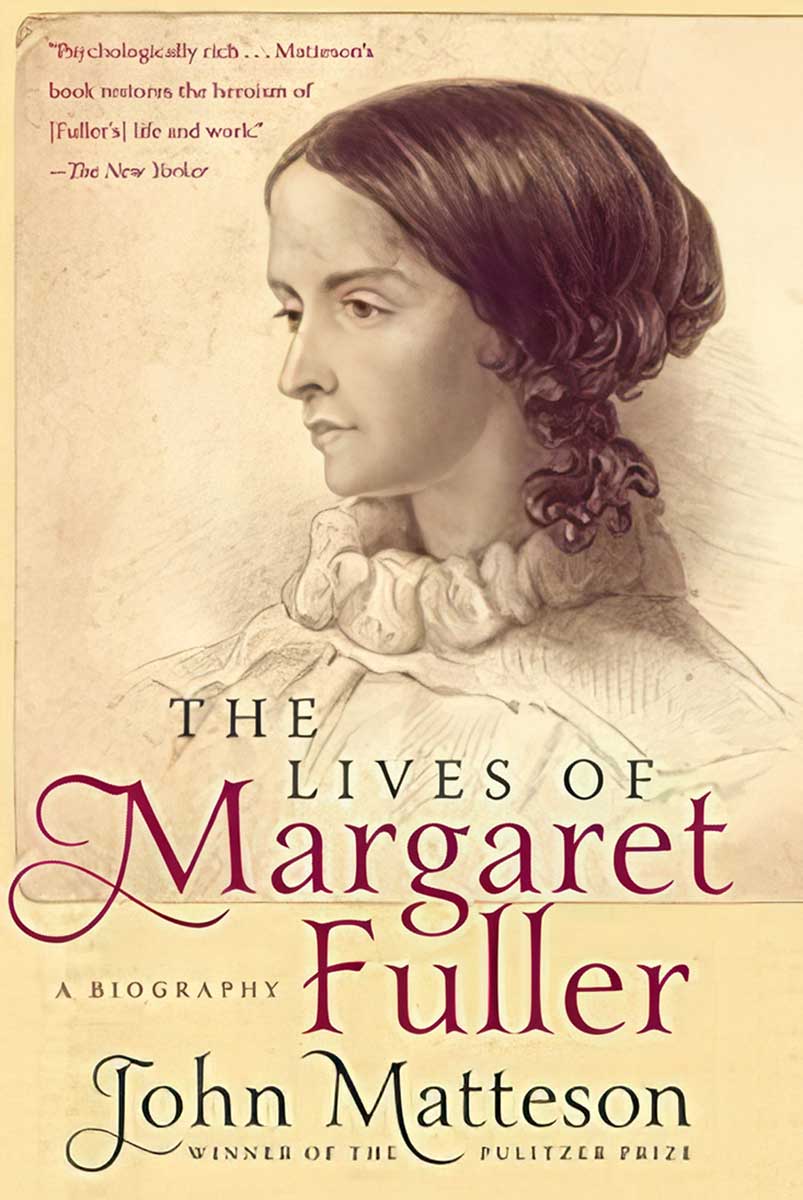

Pulitzer Prize winner Dr. John T. Matteson* discusses his significant contributions to the study of Margaret Fuller — an influential feminist, educator, and foreign correspondent—with Richard Marranca.

In a relatively short life, Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) reached great heights in and outside her circle of Transcendentalists. From early on, she was trained quite rigorously by her father, which began her ascent as a woman of letters. Margaret’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century is the first major work on feminism in the USA. She had a dazzling reputation as the leader of “Conversations,” humanities-oriented discussions mainly for women.

In the last part of her life, she was a foreign correspondent for Horace Greeley’s The New-York Tribune. In Rome, she met an Italian marquis and had a child, wrote reviews, and witnessed the revolution — in fact, she was embedded in the revolution, writing dispatches, assisting her husband on the frontlines, and managing a hospital. She had a close friendship with Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian patriot and revolutionary. Margaret Fuller was idealistic, brave, and brilliant, believing that “the only object in life was to grow.” She was a genius who combined intellect and action.

* Dr. John T. Matteson won a Pulitzer Prize for Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father and an Ann M. Sperber Prize for Best Biography of a Journalist for The Lives of Margaret Fuller. His most recent book is A Worse Place Than Hell: How the Civil War Battle of Fredericksburg Changed a Nation. John is a Distinguished Professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He has an AB in History from Princeton University, a Ph.D. in English from Columbia University, and a law degree from Harvard University. His work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and The Harvard Theological Review, among others. He is also a Fellow of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Q: I didn’t know much about Margaret Fuller until I got an NEH grant to study in Concord, Massachusetts. There, I met you and others who lectured on Margaret. Can you tell us about her?

Oh my! How much time do you have? “Who am I?” was a question that Fuller perpetually asked herself, and she was never satisfied with the answer. That’s part of the reason she kept refashioning herself into someone new.

She was the eldest daughter of a Massachusetts congressman who was a child prodigy in terms of her grasp of languages and literature. Although she lived only forty years, she compiled an extraordinary litany of “firsts” for an American woman: the first woman to edit an important literary journal (The Dial), the first woman to be granted access to the Harvard University Library (to research her book Summer on the Lakes); first regular foreign correspondent male or female for a major American newspaper (she covered the Roman Revolution of 1848-49 for the New-York Tribune). Maybe most importantly, she was the author of the first major American work on women’s rights: Woman in the Nineteenth Century. People who knew her called her a force of nature. I can only agree.

Q: What are the most important things we should know about Fuller?

For me, there are three principal features of the Fuller story that I would want everyone to understand. First is her capacity to triumph over obstacles — both the strictures imposed by a male-dominated world and the specter of her own self-doubt. I have written about a number of pretty fearless people, but Fuller is near the top of the list.

Second is how profoundly she was shaped by her desire to meet and exceed the expectations of a demanding and difficult father. I’ve always been attracted to stories of intergenerational conflict, and Fuller’s struggle with Timothy, both before and after his death, is a highly interesting and relatable story.

Finally, I always want to impress people with the protean nature of Fuller — the way she constantly reinvented herself in order to seize new opportunities and to grow perpetually as a mind and spirit. If you know who Emerson and Thoreau were at twenty, you have a good sense of who they were at forty. Not so Margaret.

Q: Your books, Lives of Margaret Fuller and Eden’s Outcasts (on the Alcott Family), are wonderful portraits of brilliant people. Even though they are influential with academics they are hardly known by the general public. Can you speak about this?

Well, it is easy for a literary and historical scholar to descend into a long grouse about how people don’t read or take the trouble to know the history of their own country. But, lost book sales and royalties aside, it really is a shame that a country that has given rise to so many inspiring and transformative lives should generally know so little about the people who made us who we are. The British writer John Ruskin wrote about how essential admiration is to a human being — not being admired by others, but rather the beautifully humbling experience of beholding the excellence of another person. America in 2023 is very bad and out of practice when it comes to admiring, and we suffer for it.

Q: Margaret was an exemplar of self-cultivation. What did this term mean for Margaret?

Unlike most of the leading opinion-makers of her time, Fuller was not a conventional Christian. I mean that she did not think that the purpose of life was to surrender yourself to Christ and walk humbly in the paths of the scriptures. Rather, she believed that the goal of life was to develop your innate potential to its utmost, whether that potential was for intellectual achievement or any other useful pursuit.

She was a devotee of the German poet Goethe, in whose play Faust, the angels declare, “Whoever strives, we too can save.”

Fuller sought her salvation by expanding her mind to its utmost. That’s why she found the restrictions placed on women so infuriating. She wanted everyone to be the most fully developed person possible. She famously said about women, “Let them be sea-captains, if you will!”

Q: Can you tell us about her family?

Fuller grew up in a neighborhood that is now part of Cambridge, Massachusetts, very close to MIT. The house where she was born, on Cherry Street, still stands. She belonged to a large family: two sisters and six brothers. Margaret was the oldest. One brother and one sister died in infancy. Another brother was mentally challenged. Her mother was a quiet woman whose greatest love was gardening. Her father was a highly ambitious lawyer who, as I’ve said, served in Congress. He was a close friend of President John Quincy Adams and also served as the Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. I have written about her younger brother Arthur, who served as a chaplain in the Civil War and was killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg. You can read about him in my book A Worse Place Than Hell.

Q: How and what did her father teach her?

He tried to teach her almost everything. But he seems to have concentrated on the literature of the ancient world. Margaret became fluent in Latin at a very early age and could translate passages from Virgil’s Aeneid when she was nine. As an adult, she was also proficient in German and Italian.

Learning from Timothy Fuller wasn’t easy, though. He subjected Margaret to marathon sessions of study that went on late into the night. Margaret became a nervous child and suffered from horrible nightmares inspired by her reading. She also acquired from working with her father the rather mistaken assumption that women could please the opposite sex by being the smartest person in the room. It was not the best social strategy at that time.

Q: Can you place Margaret Fuller in context? What were some events of her time?

Fuller lived from 1810 to 1850. It’s not a long life. However, it covered a critical period in the growth of American culture. During that time, we see the advent of the railroads, the establishment of inland cities like Detroit and Chicago, and the rise of Jacksonian Democracy. The Mexican-American War significantly expanded the country’s territory, and the storm clouds of controversy over slavery started to gather.

In music, the classical era of Beethoven and Schubert gives way to the Romantics: Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Chopin — the last of whom Fuller heard play when she passed through France. Fuller finds herself in the middle of the literary movement we call the American Renaissance. She is friends with Emerson, Thoreau, and Hawthorne. She reviews books by Melville, Poe, and Frederick Douglass.

Q: Ralph Waldo Emerson asked her to be editor of The Dial. What was this publication?

The Dial was the first avant-garde American literary journal. It published essays, poems, and experimental fiction. Its offerings included poems by Thoreau and a series of philosophical maxims by Bronson Alcott titled “Orphic sayings.” The Dial is also the place where Fuller herself published a kind of first draft of Woman in the Nineteenth Century, a long essay that she titled “The Great Lawsuit: Man versus Men; Woman versus Women.” Sadly, The Dial never made money and ceased to exist after four years or so.

Q: She was also a schoolteacher and the leader of the Conversations. Can you speak about these two roles?

Fuller’s father died when she was 25 in 1835. After that, she was always searching for ways to earn money that nevertheless coincided with her talents. She was Bronson Alcott’s teaching assistant at his famous Temple School. She also put in time at a school in Providence, Rhode Island. She taught Latin, English composition, elocution, history – even some courses in science and the New Testament. Truth be told, she wasn’t a very popular teacher. She was a perfectionist who believed in extremely hard work, and the children in her classes typically had other priorities.

She was much happier when she came to Boston and led several series of Conversations at Elizabeth Peabody’s bookstore. The Conversation was a kind of improvised public lecture with broad audience participation — a form that she and Bronson Alcott were responsible for developing. Some of Fuller’s best Conversations involved the themes and origins of Greek mythology. She was also interested in exploring large concepts. She conversed, for instance, on the meanings of “good,” “truth,” and “beauty.”

Q: Who attended the Conversations, and what were some of the themes?

With only one exception, the Conversation series was open only to women. The attendees were typically women of means from Boston and its suburbs: women of intellectual skill and curiosity who had found a dearth of intellectual substance in their daily lives. Some of the attendees became important figures in social reform and the fight to expand women’s rights: Caroline Healey Dall, Julia Ward Howe, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Q: What is a Transcendentalist, and how does Margaret fit into this group? Was she friends with Emerson, the Alcotts, and Hawthorne? And did she ever meet Goethe?

There are probably as many meanings to “Transcendentalist” as there were Transcendentalists. In broad terms, a Transcendentalist sought forms of spiritual discovery outside the limits of organized religion and tried to achieve an original, personal relation to the divine forces in the Universe. They typically believed that the evidence of one’s senses was not the last word on what constitutes reality. Transcendentalism was a chiefly bucolic movement; it presumed that seeking God in nature and agriculture was more fruitful than in the city streets.

Some, like Thoreau and Emerson, believed that one’s personal divinity was best discovered on one’s own. Thoreau, for instance, lived alone in a cabin in the woods for two years.

Others thought that community was the way to enlightenment. Bronson Alcott led followers at a vegan farm called Fruitlands. The most successful Transcendental community was Brook Farm, where Hawthorne was a sometime member and which Fuller visited frequently. (It would be a mistake, however, to classify Hawthorne as a Transcendentalist: he was both too worldly and too pessimistic to fit the term.)

Fuller had extensive relations with Emerson, the Alcotts, and Hawthorne, all of whom lived in Concord, Massachusetts during her time there. Her letters to and from Emerson make for engaging reading. However, she never knew Goethe, though she wished she could have. Goethe lived in Germany and died in 1832 — well over a decade before Fuller first set foot in Europe.

Q: Did Edgar Allan Poe and Margaret Fuller get along?

As John Wayne might have said, “Not hardly.” Poe intrigued Fuller, but she doubted his sincerity. She tangled with him over the way he behaved toward a woman whom both of them knew. Poe called her a “busybody” and wrote an unflattering description of her in his Literati of New York.

Q: Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century is considered the first great feminist study in America. What’s the book about?

It is an erudite and extended plea to those who make and enforce the rules, both written and unwritten, of society. Fuller discusses the long history of women’s contributions to civilization and argues for the reform of institutions that prevent women from becoming their best selves. Quite simply, she argued that women should be encouraged to discover their true gifts and then not be denied the freedom to develop them. She stood for, if I may quote, “the law of right, the law of growth, that speaks in us, and demands the perfection of each being in its kind, apple as apple, woman as woman.”

Q: So her Woman in the Nineteenth Century is an extended version of her famous essay, “The Great Lawsuit”?

Yes. Much of the material she added was inspired by her interactions with devotees of Charles Fourier, a French social reformer. One of my proudest moments as a Fuller scholar came when I discovered the origin of one of the quotations at the beginning of Woman in the Nineteenth Century: “The Earth waits for her Queen.” It’s from a toast delivered at a Fourierist convention in New York that Fuller attended. One hundred sixty-seven years went by before anyone discovered that. That felt pretty good!

Q: I recall that her letters, diary entries, and reviews are some of her most interesting and wide-ranging creativity. Do you have some recommendations?

My favorite writings of hers are the dispatches that she sent from Europe to the New-York Tribune. Happily, these have been published by Yale University Press in a volume titled These Sad but Glorious Days. Before going to Europe, Fuller struggled with developing a readable style. The discipline of becoming a journalist made her writing terser and much more enjoyable to read. These dispatches tell a fascinating story of an American woman caught up in an Italian revolution.

Q: Can you tell us about her travel memoir, Summer on the Lakes, published in 1843?

It’s my other favorite among her writings. She travels through the Great Lakes to Chicago at a time when the area was still somewhat untamed. She writes with enthusiasm about the burgeoning city of Chicago and with heartfelt concern about the Indigenous people she encounters on the way. The travel writing is interspersed with fascinating vignettes of other kinds. One caveat, though: avoid the version that was edited after her death by her brother Arthur. He tried to rewrite her work as a labor of love and had very little idea of what he was doing.

Q: Was she a reviewer for the New-York Tribune, and how did that position come about? What countries did she work in, and what did she review?

She was mostly in charge of book reviews (works by Douglass, Emerson, Poe, Melville, Hawthorne, and Lydia Maria Child, among others), but she also wrote about classical music events. Some of her most interesting columns were pieces of social criticism, including New York’s treatment of convicts and insane people, as well as what she perceived as the downfall of public manners.

After her stint in New York, she traveled through the United Kingdom, France, and Italy, richly documenting her travels.

Q: Can you tell us about her experience of the revolution, especially the Roman Revolution?

It was the defining experience of her life. She met her husband, Count Giovanni Ossoli. Also, as the only regular American reporter on the scene, Fuller virtually controlled American public opinion of the conflict, in which the citizenry of Rome was fighting to throw off foreign control and establish a republican form of government.

Fuller sided wholeheartedly with the revolutionaries. Indeed, after the fighting was over, no less a person than Elizabeth Barrett Browning called her “one of the out & out Reds.” Fuller found in Rome a love of justice and a patriotic zeal that she thought had more or less died out in America. She even administered a hospital for the wounded in the battles against the French army. I think it was the greatest time of her life. Amazingly, Fuller remains the only American citizen with a street named after her in the Eternal City.

Q: Who were some of her special friends during the revolution?

There was a wonderful woman from the Italian upper classes named Cristina di Belgioioso, who partnered with Fuller in her relief efforts. But the two biggest names belonged to the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz and the Roman revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini. Mazzini was an almost saintly man whom Fuller admired intensely.

Q: So, revolution is raging around Europe, and in the midst of this, she meets her future husband? It sounds like a movie. Can you tell us about this?

Ah, yes, Count Ossoli. They met in St. Peter’s Basilica when Fuller became separated from friends and got lost. Ossoli saw her and offered his services. One thing led to another, and eventually, Fuller bore his child. No one has ever been able to prove that they were married at the time, though they did present themselves in public as husband and wife. Ossoli was a member of the revolutionary forces guarding the city. As the resistance was collapsing and Ossoli did not expect to survive, Fuller joined him at the barricades.

What’s remarkable is that Ossoli was nothing like the kind of man Fuller thought she would be happy with. For one thing, he was noticeably non-intellectual and could not hold his own among the brilliant people to whom Fuller was naturally drawn. But he loved her selflessly, and they were happy.

Q: Margaret, her husband, and her son took a frigate to the USA. Why did they take this ship, and what happened?

It happened after the revolution ended and the Ossolis had fled to Florence. Margaret wanted to go home to the United States, so the family booked passage on a freighter, the Elizabeth. The accommodations were lackluster, but it was the cheapest way to go. Fuller had met the captain, a Mr. Hasty, and had firm confidence in him.

However, Hasty contracted smallpox and died before the ship had even left the Mediterranean. The mate took over the conduct of the voyage. He was a rank amateur and so bad of a navigator that the Elizabeth missed its destination of New York by fifty miles. In the dark, with a huge storm coming up, the Elizabeth struck a sandbar off Fire Island. Most of the crew members were able to swim to shore. Fuller could not swim and would not leave her child. She, Count Ossoli, and her son all perished in the wreck. Her body was never recovered.

Q: It’s a heartbreaking ending to a brilliant life. Her manuscript on the revolution went down with the ship. Did the world lose a masterpiece?

Emerson knew about the manuscript, though, of course, he couldn’t have read it. He thought the descriptions of it showed so much promise that he sent Thoreau to Fire Island after the wreck to try to find it. He failed.

Was it a masterpiece? There is no way of telling, nor is there any way to guess what Fuller’s life would have been like after 1850 if she had landed safely. Her husband was unemployable. She might have been so tied down by family obligations that her career would have fizzled out. But then again, she had so much determination that I would not have bet against her.

Q: Are there any programs or movies that you recommend on Margaret Fuller? Do you hope for a feature film?

Sadly, I don’t know of any worthwhile programs and movies about Fuller. As for a feature film, it’s funny you should ask. A friend and I have written a screenplay, not about Margaret, but about one of my other pet subjects, Louisa May Alcott. As of this interview, that screenplay has been named a semifinalist in the Academy Nicholl Fellowship competition, sponsored by the same organization that manages the Oscars. We’ll find out soon whether we’ve advanced further.

Thanks for the interview, Richard. It’s always a joy to talk about Margaret Fuller.