From 1952 to 1960, the colony of Kenya was gripped by turmoil and bloodshed as Britain struggled to maintain its hold on its African colonies. Various tribal factions known collectively as the “Mau Mau” launched a guerrilla campaign against their European oppressors. The fight for independence destroyed communities, factionalized tribes, and pitted neighbors against each other as the Kenyan people suffered through the conflict.

Marked by executions, massacres, and war crimes, the conflict known as the Mau Mau Rebellion (also known as the Mau Mau Uprising or Mau Mau Revolt) deserves far more attention in Western history books.

Leading up to the Mau Mau Rebellion

Since the British arrival in Kenya in the late 19th century, life for the people of the East African land became progressively worse. In 1888, the British government granted the British East Africa Company a charter to colonize Kenya. The influx of foreigners severely disrupted the way of life for Kenyans.

The British imported workers from India and set about the task of building a railway line across Kenya to link up with their colony of Uganda. There were several Kenyan ethnic groups living directly in the path of this enterprise, and none of them were happy about the British disruption. They understood British power, so many took a welcoming stance to the British presence, but this attempt at diplomacy quickly turned to hostility. The British did not see any reason to placate them and shot random Africans as a show of force.

The Maasai people avoided confrontation, while the largest ethnic group, the Kikuyu, tried to fight back. The British colonial forces’ response was brutal and included executions and punitive expeditions. Combined with famine and disease that had gripped the region, the effects were disastrous for Kenyan communities.

The influx of European settlers and the seizure of land turned the native population into poverty-stricken agricultural workers. After the First World War, the process continued, and ex-soldiers were given what little land remained, reducing the native ownership of land to virtually nothing. Organizations were formed in protest, such as the East African Association (EEA) and the Kenya African Union (KAU).

By the end of the Second World War, vast communities of Kenyans lived in slums. Those who lived outside the cities were pushed into tiny reserves. With no justice and with mistreatment by European and Indian settlers, discontentment grew, and with it came the Mau Mau Rebellion.

The Early Phase of the Mau Mau Rebellion

The constitutional change sought by the KAU was not enough for some radical elements within Kenyan society. Young Kikuyu were especially disillusioned. Being reduced to squatters on their own land, their disillusionment turned to violence which began to spread. Initially, this violence was realized as small-scale attacks and acts of sabotage on European-owned land.

Where the name comes from is unknown, but these fighters became known as the “Mau-Mau,” and they grew in number spreading across the major population centers and using the highlands to wage a campaign of resistance. Moderate elements in Kenya were swept aside as emotions boiled over. Under the rule of Kenya’s governor, Philip Mitchell, the British made little attempt to placate the Mau Mau, whom they saw as a nuisance rather than a serious threat.

After Mitchell retired, however, the acting governor Henry Potter began to take the situation seriously, and he sent increasingly alarming reports back to London. In September 1952, Sir Evelyn Baring arrived in Kenya to take up the governorship, but he had not been advised properly about the maelstrom into which he was stepping.

The KAU increasingly adopted an anti-Mau Mau stance. However, this was extremely unpopular with the Kenyan people, and 90% of the Kikuyu people took the Mau Mau oath, swearing to resist British rule. When a prominent Kikuyu chief collaborator was assassinated, the Mau Mau celebrated.

When the British finally realized the danger, they acted to quickly end the rebellion, declaring a state of emergency and by arresting 180 suspected Mau Mau leaders, including future prime minister and president Jomo Kenyatta, and submitting six of them to a show trial. This failed to produce the necessary results, and the British were forced to resort to harsher measures.

Atrocities were committed by both sides. In 1953, the Mau Mau rebels herded men, women, and children into huts in the village of Lari and burnt them, hacking with machetes at those who tried to escape. Thousands of others were murdered. The most famous murder of a European was that of 6-year-old Michael Ruck, who was hacked to death along with his parents and one of their farmworkers in a coordinated attack aimed at white settlers. Most of the violence committed by Mau Mau fighters was, however, directed at Kenyans who fought for the British government. Many Mau Mau members were sickened by the actions of their comrades, and denounced the violence.

British war crimes and abuses were legion. People were executed in villages, and concentration camps were set up in which conditions were appalling, violence was rife, detainees were denied access to medical aid, and women were regularly raped. Torture methods included starvation, burning, raping, castration, whipping, and sexual abuse. Governor Evelyn Waring was aware of the treatment of the prisoners, but took no action.

The Colonial British Ramp up Operations

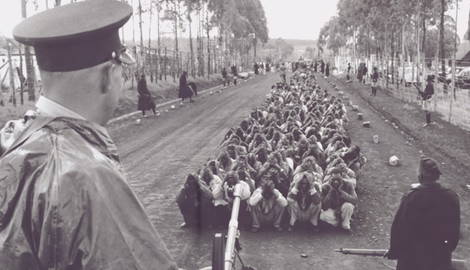

In 1954, the British enacted Operation Anvil. Nairobi was the center of Mau Mau control, and a force of 25,000 British troops sealed off the city and went house to house, purging it of suspected Mau Mau rebels. All members of the Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru tribes were detained. Tens of thousands of people were removed from the city and put in reserves.

In the dense forests where Mau Mau fighters operated, massive bombing campaigns were undertaken by the Royal Air Force. By June 1954, six million bombs had been dropped. The campaign, known as Operation Mushroom, was mostly successful, breaking up bands of Mau Mau in the forests and forcing them to relocate to the reserves.

More detention and screening camps were built, most without government authorization. The British attempt to win the war through socioeconomic and civic reform backfired, and the camps ended up being described as a gulag. The detention and rehabilitation program was named “The Pipeline,” and detainees were classified by their level of dedication to the Mau Mau cause. These designations were “white,” “grey,” and “black.” “Whites” were cooperative detainees, “greys” were seen as compliant and were moved to work camps, while “blacks” were considered devout Mau Mau supporters.

By 1955, the detention camps began to produce results. Many detainees confessed and gave information on their fellow Mau Maus. One of the most famous defectors was Peter Muigai Kenyatta, Jomo Kenyatta’s son. Violence was rife in the camps. The detainees formed their own system, killing spies and brutally murdering those who refused to join their war against the British. The British, in turn, were also brutal in running the camps, issuing beatings and hangings.

Disease was rife in the camps. Tuberculosis, dysentery, scurvy, and typhoid all made the rounds, forcing the closure of several camps.

The British campaigns also consisted of a process of “villagisation” whereby rural Kikuyans were relocated to villages under British control where they could be more easily monitored. In the space of just over a year, a million Kikuyu had been forcibly relocated.

The End of the Mau Mau Rebellion

In 1955, after successful bombing campaigns, British army forces swept through the forests, killing or capturing the last of the Mau Mau able to launch an effective resistance. With their commanders captured or killed, the Mau Mau Rebellion petered out. The last remaining fighters were focusing on surviving rather than fighting the British occupation. In October 1956, the most important Mau Mau commander, Dedan Kimathi, was captured and put on trial. This arrest effectively ended the rebellion.

Although a state of emergency remained in place until 1960, by 1956, the rebellion was over and it had been brutally crushed by the British, who had taken a multi-pronged and heavy-handed approach to dealing with the situation.

The official death toll among the Mau Mau is reported to be 11,503. This figure is, however, most certainly wrong, and the real death toll is thought to be much higher. In contrast, a total of 32 white Europeans are claimed to have been killed by the Mau Mau. This latter figure served as the basis for the entire British reprisal against the Mau Mau. The British campaign is thus seen today as a massively disproportionate use of force.

The Results of the Mau Mau Rebellion

Although the Mau Mau Rebellion was mercilessly crushed, it exposed the weaknesses of British rule. The measures the colonists had gone to suppress and defeat the popular uprising were a testament to their desperation and determination, and the people of Kenya realized their British overlords were not invincible.

As the 1950s drew to a close, nationalism in Kenya had rapidly accelerated putting the nation on a path to inevitable independence. Agrarian sectors, in particular, became politicized, and the mass of the population was made politically aware of what was happening and what needed to be done.

Many decades later, Kenya still bears the scars of what happened. In 2013, the British government agreed to pay almost £20,000 to many thousands of claimants who had demanded compensation for the horrific experiences they suffered at the hands of the British Empire.

Today, the Mau Mau Rebellion garners mixed emotions. On one hand, it was a popular movement that served to inspire feelings of nationalism that would lead to independence. On the other hand, it was a time of intense brutality in which unspeakable horrors were inflicted on human beings from both sides of the political divide. Many people find it hard to reconcile justice with the intense cruelty that was used to attain it.