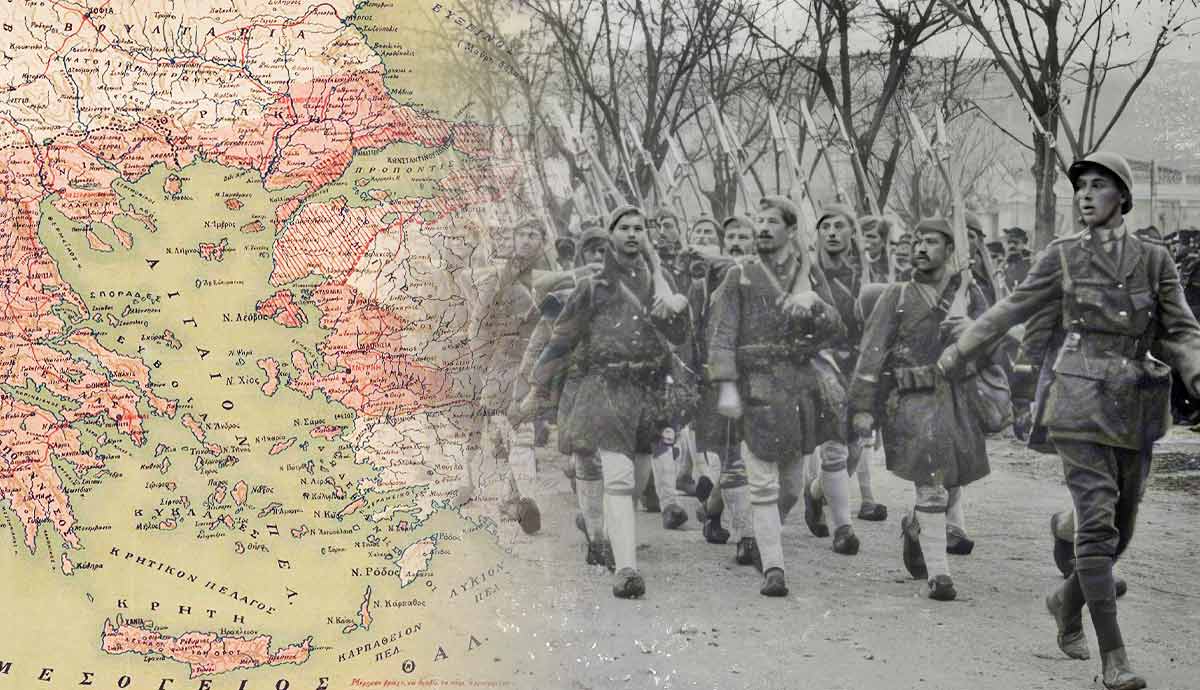

The Balkan Wars (1912-1913) proved that the Megali Idea—the nationalist concept and goal to expand the Greek state to include all ethnic Greeks and historically Greek territories—was a tangible dream. Under the strong political leadership and intense diplomatic efforts by prime minister Venizelos, along with the inspiring military command by King Constantine, Greece emerged victorious.

This was still a time in Greece when the Megali Idea was promoted and conceptualized unanimously, and faith in the ideal was enough to overcome other antagonisms. Once the First World War erupted, however, disagreements would resurface, and this time, different approaches to the ideology, coupled with different foreign policies pursued by each side, would lead to an unprecedented rupture—the National Schism—almost engulfing the country in civil strife. Thus, it would be in the frames of the National Schism, arguably a by-product of the Megali Idea, that in 1920, the ideal would reach its apogee and, two years later, its conclusion.

Megali Idea, WWI, and the National Schism

For diplomatic and strategic reasons, in 1914, Sir Edward Grey asked Greece to assist in the Gallipoli operation. Venizelos, maintaining a policy friendly to Britain and foreseeing the eventual victory of the Entente, immediately propagated for participation.

However, King Constantine was the brother-in-law of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II, and his trusted officers of the General Staff, advocated neutrality at least until the Entente would secure a more certain outcome in their favor. The Austro-Hungarian invasion of Serbia (1914-1915) also sparked controversy since Venizelos and the Staff debated whether Greece should assist its ally (by treaty, since 1913). For Venizelos, participating in the war on the side of the Entente meant that, upon victory, the zone of Smyrna on the coast of Asia Minor could be claimed by Greece due to its solid Greek community. The Allies, however, remained very hesitant to proceed with such promises.

The Royalists not only knew of this hesitation but also feared that entry into the war would put the Greek community of Smyrna at risk of further pogroms by the Ottomans. There was also the risk of losing newly annexed territories to Bulgaria. Both sides believed that their policy was the one that better served the “Megali Idea” and, initially, Venizelos gave ground. However, as debates on foreign policy became heated, Venizelos proceeded with a fateful decision. He allowed Entente troops evacuating Gallipoli to land in Thessaloniki without first consulting with the King. They would allegedly assist the Serbian army, but the city immediately became an Allied camp, and a new front, the Macedonian, opened by October 1915. The direct violation of Greek neutrality was a serious blow to Venizelos’ popularity. Having resigned from Premier two times in 1915, he abstained from the upcoming elections in December. Hostilities between supporters of the two sides became more and more common in what came to be known as the “National Schism.”

The Long 1916

By early 1916, most people sided with Constantine’s neutrality due to the Entente’s authoritarian and harsh occupation of Thessaloniki and the prevalence of anti-war feelings. Yet, events would favor Venizelos. To counterbalance the Allied presence in Thessaloniki, the Central Powers demanded the surrender and temporary occupation of Greek Eastern Macedonia. The Greek Royalist government agreed. The Greek army mobilized preemptively in 1915 to face possible Bulgarian threats but was ordered by the Royalist government to stand down as Bulgarian troops invaded.

Many dissatisfied officers, believing that the Royalists had betrayed Eastern Macedonia, fled to Thessaloniki and organized a revolution, later recognizing Venizelos as head of their movement. The Royalist insistence on maintaining neutrality backfired as public opinion partly shifted against them.

Yet, dependency on foreign support barred the movement of Venizelos’ “National Defense” (as it became known) also from being widely popular. The Venizelist revolutionaries were termed “agents of foreign interests” and Venizelos himself was connected to servitude to the Entente while Constantine was still largely linked to independence. The declaration of the National Defense effectively meant that Greece was divided into two separate states, with Venizelos forming a government in Thessaloniki and Constantine remaining in Athens. With political turbulence at an all-time high and with Central Powers unable to support their “ally” Constantine, the initiative passed to Entente. The Allies, anxiously seeking a resolution, decided to land French detachments in the port of Piraeus. In the battle that ensued with the many demobilized recruits that supported the Royalists (Reservists), the Allies were forced to retreat within two days. Then, minor acts of hostility between supporters of each side suddenly intensified. The Royalists unleashed a bloody pogrom against Venizelist supporters, Venizelos himself being symbolically even excommunicated.

Greece Joins the War

The Allies did not give up. For the next six months, southern Greek ports were blockaded, and food shortages caused great suffering throughout the mainland. By June 1917, under intense diplomatic pressure, the King was forced to abdicate. Venizelos returned to Athens and unified the country. Still, he never surpassed the King in popularity, especially in southern Greece.

The Allies, whom Venizelos represented, had seriously alienated many Greeks. Thus, Venizelos faced much dissent which he suppressed by harsh and often unfair measures. The public sector, including the army, was purged from most Royalists. His own supporters enjoyed numerous benefits. Still multiple matters remained unresolved, and Venizelos even imposed martial law to impose the reforms without hindrance. For his opponents, 1917 marked the start of a “Venizelists’ Tyranny.”

With the country now officially at war with the Central Powers, the army was reorganized. Venizelist officers had already mastered three divisions—the National Defense Army Corps—composed mostly of volunteers who had joined the Allied Army of the Orient—stationed in the Macedonian Front—since 1915. Partial conscription was now called with the aim of gradually becoming a general one. With the forces on the Macedonian front slowly but steadily increasing, the Royalists, primarily via the Reservists, made their last bid against Venizelos by trying to avert the conscription. The once more conscripted Reservists started rebelling in various units. However, by September 1917, discipline was restored, again with very harsh measures, and a great number of soldiers were sent to the front, although morale remained shaky. The actual Greek contribution came down to only six months, but it was notable. The aforementioned National Defense Army Corps, armed and trained by the Entente, went on to fight in the battles of Skra di Legen and Vardar offensive.

The Paris Peace Conference

Venizelos’ gamble had been successful. However, as the Royalists had feared, the territorial gains were far from secure. In the Paris Peace Conference, the Greek delegation headed by Venizelos worked tirelessly to justify the Greek claims in Asia Minor. Demographic and historical arguments were employed. The Ottoman Empire did not have any say, but the victorious powers were not unanimous in the final settlement of the Eastern Question. Territories in Asia Minor had also been promised to Italy. Venizelos, trying to appease the Allies, agreed to send two divisions to Ukraine to support French soldiers against the Bolsheviks. More importantly, the quarrelsome stance of the Italians ultimately allowed philhellene British premier David Lloyd George to convince the rest of the decision-makers to allow a Greek force to land in Smyrna on policing duties. Intercommunal violence, primarily between Muslims and Christians, was expected.

For Venizelos however, the permission was perceived and projected as the first step towards annexation. After all, the grievances caused by the imposition of his regime could only be silenced with such great gains. The landing of a division on Smyrna (today Izmir) in May 1919 was seen as the implementation of the Megali Idea. Enthusiasm overshadowed, at least on the homefront, the fact that immediately upon the landing a clash with the Turkish garrison broke out, resulting in soldiers and civilians dead from both sides. Likewise, soon afterwards, irregular troops—either spontaneously or obeying the call of the resistance leader Mustapha Kemal—started harassing the Greek army but also the Greek Orthodox populations all over Anatolia. By the end of 1920, The Greeks fielded nine divisions in Asia Minor and, to suppress irregular activity, had more than doubled their original occupational zone. Mostly under Allied overall command, the Greek army found itself fighting a guerilla war, trying to protect the Greek communities but also often behaving sketchily toward local Muslims.

The Treaty of Sevres

That was the situation when, in August 1920, the Treaty of Sevres was signed. Venizelos’ diplomatic skill once more carried the day. Greece was granted Eastern Thrace, but, more importantly, rule over the region of Smyrna. The army, however, was already active and trying to secure a zone greater than the one delimitated in the treaty. The treaty itself was arguably too theoretical and fragile, already nullified on the ground, with Kemal’s influence and political authority in Muslim Anatolia growing fast. Disagreements and antagonism between the Allies intensified. Moreover, for Greece, signs of an army fighting almost uninterruptedly for 8 years were showing. National funds were exhausted. The homefront was in unrest, only partially pacified by the diplomatic success, and still very much longing for the return of the Κing.

Perhaps then, Venizelos’ defeat in the elections of November 1920 should not come as a surprise. Venizelos, in one of the rare cases in history, decided to call national elections amid an ongoing war in an effort to pacify the homefront and legitimize his cabinet which had been imposed by the Allies in 1917. The Royalists, vaguely promising an end to the war, won.

Ultimately, however, restored King Constantine and the Royalists picked up Venizelos’s campaign in Asia Minor. The army, reformed and reorganized once more, this time to accommodate the Royalist officers replaced in 1917, did not face irregular resistance alone anymore. Already in January 1921, in the battle of İnönü, it faced regular Kemalist formations. Although the initial clash was ambivalent, the Greek forces suffered a major defeat in March.

With Kemal gaining ground both in diplomacy and on the field, the Greeks launched a third offensive, this time succeeding. The Kemalists were pushed back into a fortified position on the banks of the Sakarya River. By September 1921, the two armies would embark on the lengthiest and bloodiest battle of the war, resulting in the withdrawal of the Greek troops. Exhaustion, casualties, and low morale meant that the Greek army would not be able to take any offensive initiative anymore; Greece’s diplomatic standing likewise suffered a tremendous blow, with France and Italy openly turning to Kemal.

The Death of the Megali Idea

A year passed when the Greek army tried to fortify and secure a huge zone in Asia Minor. All efforts of the Greek government had now turned to diplomacy and the last willing ally, Britain. Amid financial hardship, political instability, diplomatic isolation, exhaustion, and tactical challenges, the army barely maintained cohesion. This was not the case with the Kemalists, who not only managed to replenish losses after Sakarya but were now supplied with the latest material from Italy, France, and the Bolsheviks.

They were also driven by the mission of securing the survival of their nation, the nascent Turkish state. In August 1922, the Turks unleashed an offensive that the unsuspecting and unorganized Greeks had little chance to counter. The huge and, at places, undefended front was penetrated, and the army fled in panic. Whole divisions were either captured or dissolved. Among the troops evacuated back to Greece, few managed to withdraw organized.

Fighting ended with the Kemalist forces entering the city of Smyrna, where Christian populations had fled. The city was torched and witnessed atrocities. A lot of factors led to the Greek defeat. One of them was the ongoing political antagonism, often manifested in violent outbursts between Royalists and Liberals even on the frontlines. Immediately, once the army was evacuated and before even reaching the mainland, a group of Liberal colonels organized a coup against the Royalists.

The government, burdened with the defeat, capitulated. A tribunal, called in October by the revolutionary authorities, rushed to whitewash the Liberals of any mistake during the campaign, incriminating for the defeat and executing for high treason five of the Royalist politicians and the last Royalist commander-in-chief. While certainly, this was a sham trial and the executed were mostly mere scapegoats; the Royalists were tarnished and burdened with the defeat for many decades to come, a perception that greatly influenced historiography.

Post-Disaster Greece & The Legacy of the “Megali Idea”

The war officially ended with the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, dictating the exchange of Christians of Anatolia with Muslims of Greece, the former being more numerous. Waves of refugees had already started fleeing Anatolia even before the evacuation of the Greek army. The war and the treaty that concluded it have many readings. For the Turkish state, it was its birth point. For Greece, it was the greatest catastrophe the country had ever experienced. For the Turks, the war was a struggle for independence. For the Greeks, it was also, from a certain point of view, a liberating crusade. It was also the apex but also the death of the Megali Idea, unceremoniously concluding a decade of wars that began in 1912. Greece would still gain the Dodecanese from Italy after WWII, but that was rather a by-product of the country’s participation in the conflict. The irredentist ideal had died in 1922 since, after all, the country had largely attained homogeneity following the population exchange.

The Megali Idea began as a noble and lofty ideal, spreading through society and exploited by politicians to pursue their goals. Since 1912, when Venizelos managed to modernize the army, the ideal motivated for the most part officers and soldiers with noteworthy results. The fact that this notion always remained a vague conception meant that its uniting capabilities turned to dividing factors once different interpretations were proposed. When that happened, primarily during WWI, the nation itself was divided over an allegedly national ideology, with supporters of one interpretation accusing those of the other even of high treason. Gradually, this antagonism overshadowed the ideal itself. It certainly outlived it. While the Megali Idea died in Smyrna, political antagonism would continue well into 1935, with the scene dominated by coups and counter-coups. The antagonism between Liberals and Royalists would evolve into a clash between left- and right-wingers, eventually culminating in a frank civil war.