Following the war, a revolution in acting was bowing on the New York stage. The first uprisings came in the 1930s with the introduction of the concepts of the pioneering Russian theater director and teacher, Konstantin Stanislavsky (1863-1938). From traditional acting styles that stressed the artificial and the mannered, Stanislavsky’s U.S. acolytes would instead adopt naturalistic techniques that stressed lived experience. The eventual legacy would be a storming of the studio gates by generations of stars, from Marlon Brando to Paul Newman, Jane Fonda, Dustin Hoffman, and many others.

1. Before Method Acting: Stage to Screen

Beginning in the silent era of motion pictures at the turn of the 20th century, screen acting had taken its cue from the expressive, histrionic styles of the 19th-century stage. Since theaters then were generally large, with thousands of seats on several levels, actors by necessity had to project, not just with their voices but with their bodies too. The resulting performances were typically full of broad gestures, crafted movements, and exaggerated expressions. At its extreme, such acting was calibrated so that specific stances or gestures would indicate specific emotional meanings. In addition, since the American stage was derived from a classic British one that revered Shakespeare’s dense, metered dialogue, great emphasis was placed on clear, precise (and usually loud) annunciation.

Lacking the aural dialogue of the stage, silent-screen acting was even more dependent upon physical gestures. True, the use of printed dialogue “intertitles” helped convey story material, but too many were distracting to audiences and, in fact, a good number of early spectators—especially immigrants—were not fluent in English. Silent film acting only began to be more subtle with the momentous innovation of the camera close-up, especially to capture facial expressions, for instance in the 1920s performances of Lillian Gish in director D.W. Griffith’s hugely influential feature films.

2. Lights, Camera, Sound

As the “talkies” revolution resounded through Hollywood in the wake of Warner Bros 1927 hit The Jazz Singer, new acting styles also were called to action on the set. While some of the broad performances stayed, especially in comedy, Hollywood was now looking for actors (and scripts) that were indeed “stagey.” The melodramatic acting of the silents that largely seems dated today was edged out in the 1930s by what can be called the romantic or classical period of Hollywood acting.

This was the era of the glamorous, larger-than-life matinee idols, from Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, Bette Davis, and Gary Cooper and on to Cary Grant, James Stewart, Humphrey Bogart, John Wayne, and Barbara Stanwyck. Their talents centered not primarily on acting proficiency, but on elusive star charisma, looks, and ability to capture and hold the camera with distinctive line readings or facial expressions. While many of these actors were from the New York stage, they learned early on in Hollywood that less is more. Overtly theatrical acting in film is not only unnecessary, it is usually unconvincing.

One could say that classical Hollywood acting was more “realistic” than that of the silent era, depicting life-like actions and behavior seen in the everyday world. But in fact, it is almost as artificial and mannered, if taking into consideration not just the acting but the star vehicles themselves. Whether a John Wayne Western of the Fifties, a Humphrey Bogart crime film of the Forties, or a Joan Crawford melodrama of the Thirties, their characters were typically variations on the same theme. While there were exceptions, they invariably played sharp, savvy, tough-minded, ultimately heroic protagonists who usually triumphed over the odds at the end, even in a shady or hostile world.

3. Enter the Group Theater, Stage Left

While it can be argued that Bogart, Wayne, or Grant essentially “played themselves,” it almost always was some idealized, romanticized version of them. In the bigger picture of what’s judged as true to life (or “verisimilitude”), these and other classic stars delivering their lines never accidentally stumbled over their words, talked over people, mumbled, cursed, or even did such banal human actions as to go to the bathroom. Some of this artifice, of course, was due to Hollywood’s strict censorship codes, which were enforced from the mid-‘30s to the mid-‘60s.

All of this was exactly what the U.S. Stanislavsky schools were reacting to, and against. While the major Hollywood studios were embedded in the U.S. corporate system as far back as the 1920s—with its emphasis on safe, marketable, family-friendly mass entertainment—the Stanislavsky acting philosophies arose from small, non-commercial, left-leaning theatrical organizations of New York City in the 1930s.

First and foremost was the Group Theatre, founded in 1931 by director/critic Harold Clurman, producer/director Cheryl Crawford and director Lee Strasberg. Seizing on the ideas of Stanislavsky and his Moscow Art Theatre via the teachings of his protégé Richard Boleslavski, Group members forged ahead in their project to create a naturalistic, immediate, socially aware alternative to Broadway escapism.

4. Strasberg vs. Adler

While the Group Theatre disbanded in 1941, beset by financial and personality issues, it produced a number of stage hits, among them Awake and Sing and Golden Boy, by its home-grown playwright, Clifford Odets. But the legacy and influence of the Group lies more so in performance than in its actual productions. In 1947, With Robert Lewis, Crawford joined with another Group directing alum, Elia Kazan, to form the Actors Studio, planned as a small, select rehearsal and finishing school devoted to Stanislavsky’s principles. That dedication became more extreme (and divisive) in 1949, when another ex-Group member, Lee Strasberg, took over as artistic director. In what would become the longest-running personality/pedagogic feud in 20th-century acting, Strasberg and his brand of “Method” acting would clash with other Stanislavsky adherents—chiefly Stella Adler, whose most famous pupil was the great Marlon Brando.

In general, however, what is meant by the umbrella term of Method acting? As a reaction to both the artifice of 19th-century melodramatics and Hollywood’s idealized matinee idols, those schooled in Stanislavsky were taught, as a rule, to build a character “from the inside out.” Of course, it means learning one’s lines and knowing his/her interactions with the other characters and the settings. But it also means understanding and identifying with the character on a deeper level. What makes him/her tick? What would she have in her purse? If you’re playing a taxi driver in New York City, how else can one know that part of him other than by experiencing what a taxi driver does on a daily basis? Indeed, for his research into his indelible Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (1976), Robert De Niro took a job for several weeks driving a cab in New York City.

5. Outside In

On the other hand, actors in the classic British school are known for building a character “from the outside in.” Arguably, the U.K.’s greatest 20th-century thespian, Laurence Oliver was renowned for paying special attention to the outward appearance or traits of his characters, however, embellished with hairpieces, costumes, false noses, exotic accents, or, in the case of his Richard III, a hunchback. To such actors, the actual text is crucial and sacrosanct. It must be learned, examined, and diligently practiced. While lived experience can be helpful (e.g. De Niro’s taxi job), nothing compares to the truth of the character embodied in the author’s words and deeper subtexts. For the traditional actor, it’s imagination that counts, not experience.

6. Method to Madness

Especially at its extremes (e.g., James Dean), Method acting is given to introversion as well as emotionalism. One of the chief criticisms of Strasberg was his strident focus on “emotional memory” that allowed and indeed encouraged actors to dredge up specific, even painful or embarrassing personal memories as a way to more truthfully dramatize what a character is going through, thus uniting actor and character. This technique can result in powerful, gripping performances in which the actor or actress is said to “inhabit” a role; it also has led to innumerable examples of actors either indulging in scenery-chewing spectacles or insisting on staying in character even when filming has stopped.

Whereas the classical U.K. actor treats the script with respect, even reverence, the American Method actor sometimes resorts to improvisation and spontaneity, that is, if the director allows such leeway. Brando, of course, was famous (or notorious) for this. One early example of him going “off script” was in his Oscar-winning On the Waterfront role, when Eva Marie Saint’s Edy drops her glove while walking with Brando’s Terry Malloy at a New Jersey playground. In a backhanded way of prolonging the stroll, Terry picks up the glove and mischievously tries it on while Edy stands by, too shy or polite to take it back.

7. Living the Part

This potential for improvisation in dialogue or actions, galvanized by the actor(s) working in a particular scene, can be especially fruitful in rehearsals, both in theater and in film. But the process also hearkens back to Stanislavsky’s notion that a good performance can tap into the actor’s (and the audience’s) subconscious as he/she “lives the part.” In this strange sort of performative alchemy, the actor is not slave to the text but necessarily and dynamically completes it.

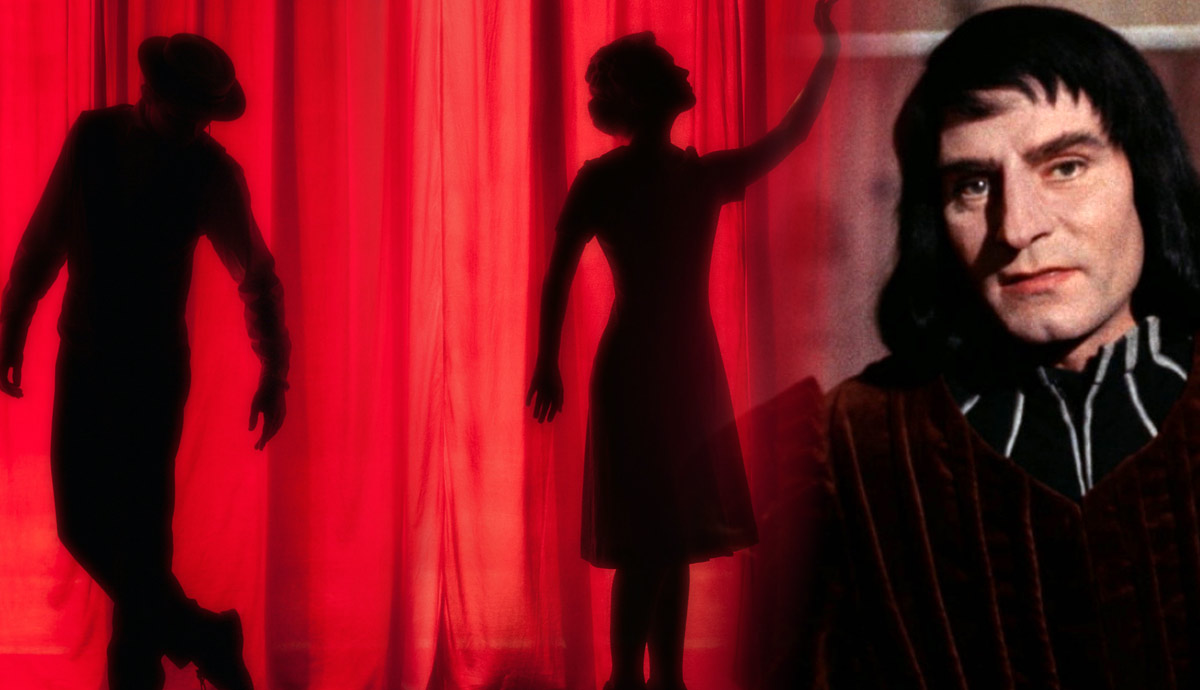

While the breakthrough of U.S. Stanislavsky-inspired acting is almost always credited to Brando’s legendary performance as the brutish Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, first on Broadway in 1947 and then in the 1951 film—both directed by Kazan—it is unfair to give Brando all the curtain calls. Others preceded and were contemporary to him, even if they didn’t get his thunderous acclaim. In truth, actors and actresses of all types and all schools build their characters and their performances utilizing a variety of strategies. Yet during the 1950s heyday of the Strasberg Method, both beginners and veterans flocked to the Actors Studio, eager to hone their craft at what was America’s most celebrated acting laboratory.

8. Method Acting and Anti-Stars

One can see the influence of the Method/Stanislavsky school today in any number of ways, even as other types of acting vie with it. Most obviously is the decline, if not total disappearance, of the classic Hollywood star. Of course Hollywood still has stars. But since actors are more or less free agents now, the big names choose their films and rarely want to be stuck playing virtually the same role again and again (unless perhaps you’re Tom Cruise). This has allowed actors to take on a wide range of parts, often to great acclaim. It certainly has opened the floodgates for all sorts of anti-heroic, oddball, and unsavory lead characters. Dustin Hoffman is a superb example. No traditionally handsome or rugged Hollywood lead, he built his distinguished career playing a raft of wildly different characters, so much so one can hardly say he ever has “played himself.”

Or consider Charlize Theron. Had she been a Hollywood star in the old days, she would have surely been locked into glamorous or romantic roles capitalizing on her beauty; there is no way she would have been allowed to “stretch,” even a little, to play anything like her road-warrior Furiosa in Fury Road, or her cold-blooded, slovenly serial killer in Monster, which won her an Oscar for Best Actress.