The term modernism refers to a movement in the arts which was keen on portraying conceptions, and the experiences, of modern society. Originating in nineteenth-century France, modernist art would reach a worldwide audience for its daring experimentations in subject matter and style. The oeuvre of modernism was so diverse because modernity, as a subject, offered such a compelling and fertile ground for representation. Art and the artists were trying to figure out what it meant to be ‘modern.’ It was a piecing together of society as it moved around them.

Introduction To Modernist Art

The word ‘modern’ implies contemporariness, or new, but when we are thinking about modernist art, the word ‘modern’ relates to specific changes in society and culture. Modern society was the product of the industrial and scientific revolution, signaling the end to an old way of cultural lived experience. Modernity, and what it meant to be modern, became a self-conscious attitude for artists in the nineteenth century who had become aware of how society had changed, and how this should be represented.

We begin to see, in the mid-nineteenth century, an artistic preoccupation with aspects of society that were deemed ‘modern’; the rising wealth of the middle-class; technological inventions; and urban culture and secularism. Experimentation in art, however, was not warmly welcomed, and it would take the boldness of individuals, risking their reputation, to place a mirror before this new society.

The Avant-Garde And Society

There is a clear reason why modernism would begin in France. The French revolution at the end of the eighteenth century had brought up the question: “how do we make a free, equal, society?” It was this self-consciousness of French culture at the time that set the scene for an artistic engagement with modern society. The term, ‘avant-garde,’ originally used in a military context to mean the ‘first man out,’ was adopted by the Socialist Henri de Saint-Simon. It then described an artist who would serve the needs of the people and society, not the ruling classes.

The avant-garde, then, would need to understand modern society if there were to paint for the people. This meant doing away with the traditional syllabus of painting as prescribed in academies, and as judged in the Salons; mythological themes, biblical scenes, and historically significant events were out of touch with the reality of modern society. This desire to paint ‘real history,’ the stuff of everyday life, was what prompted the first modernism art movement: Realism.

Courbet, the founder of Realism, was a socialist, therefore directing his gaze to the subjects of the working classes. He found a way in painting a way to represent those people that society had overlooked in its increasingly capitalistic enterprise. Realism, without political affiliation, would be extended to ask the essential question of modernist art: what is the ‘real’ experience of modernity?

Modernism And The City

The city and urban culture would become a symbol of modernity. It boasted a remarkable experience with its constant shifting of crowds, technological advancements, and looming buildings; a complex microcosm of human achievement. Many migrated from the surrounding rural areas to gamble with the chance of accumulating wealth in the city. The city provided an idea of optimism and chance; a fast-paced exciting experience unknown to village life.

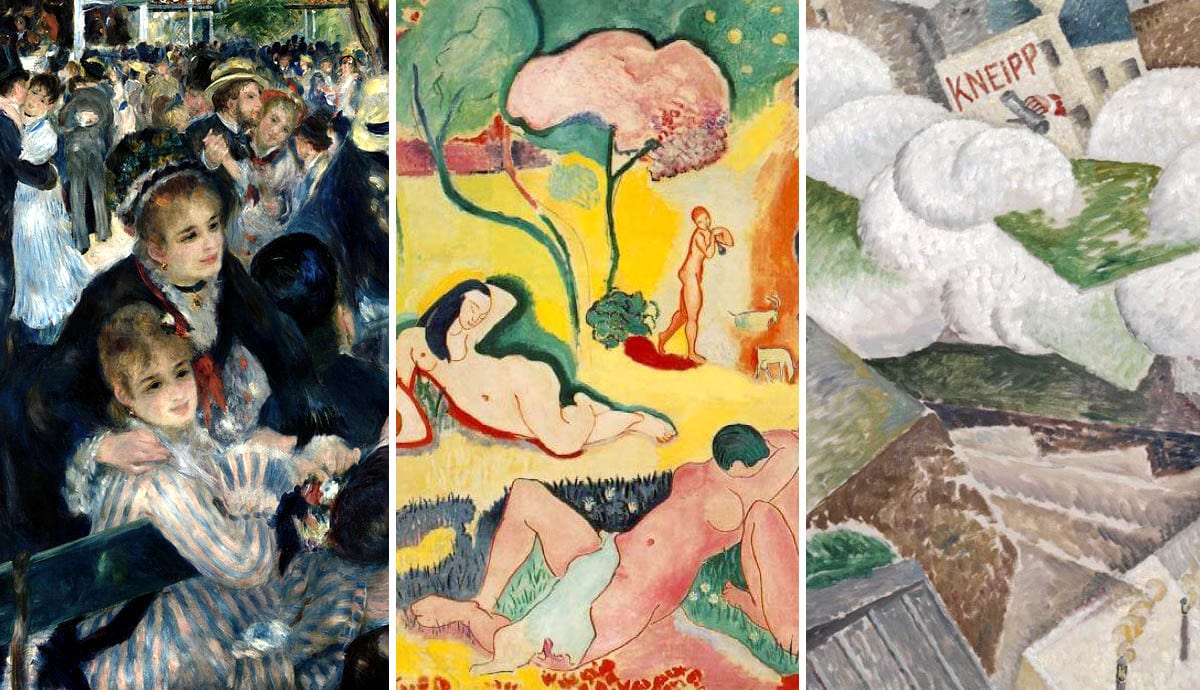

Modernist art would begin its journey of representing the city in the 1870s with Manet and the Impressionists. Realism had thrown off the weight of academy painting and the Impressionists followed suit, being among the first to recognize the artistic fertility of the city. Their painting tried to capture this fast-paced, shifting, experience of city-living and in this, they developed a new style, and subject, for painting. It was a style for modern life. It was mocked by the traditionalists of the Salon but because modernity afforded a new middle-class wealth, Impressionists such as Renoir and Monet could paint for private patronage.

The city, however, would come with an underside of alienation and anonymity. The individual could feel overwhelmed by the sheer size. They may have also felt isolated with their person belittled, and the people around them in constant movement, unreadable and uncaring. These feelings would be given a visual language by Edvard Munch, and later, the German Expressionist group, Die Brucke. Munch developed early expressionism in his efforts to represent the loneliness and unsettling anxiety he felt to be at the heart of the city.

The Drama Of Representation

As the nineteenth century ended, the long-standing tradition of painting was being deconstructed in order to find a new form that would suit modernity. The traditional style was based on the Renaissance idea of what a painting should be: a rationally constructed space with a singular perspective, as though one is looking through a window. It became apparent that this style of painting did not reflect modern values.

Modern values had gradually morphed society in a different direction. The belief in organized religion waned for many in the Enlightened west. Capitalism began to triumph over landed aristocracy, creating a stark divide between classes within society. Industry and invention promoted an idea of optimism, whilst the new science of psychoanalysis revealed the troubling notions of man being at odds within himself. For a modern citizen in the city, life appeared multi-faceted, fragmented, and confusing.

What emerges in modernist art is the individual’s will to create and explore new avenues to reflect this new reality; they were searching for a new visual language. This led to a proliferation of art movements around the turn of the century with each vying for the idea of modernity. By the end of the opening decade of the twentieth century, the viewing public had come to expect a new visual shock in the form of an art movement.

Elation And Abstraction

The magnitude of movements in the early twentieth century is itself a lesson in understanding the contradictory mood of this time. For example, where Ernst Ludwig Kirchner found alienation and anxiety in the city, members of the Section D’Or found beautiful connectivity; Futurism tried to depict the beauty of movement and the fast-paced flurry of modernity whereas Suprematism found refuge in simple geometric shapes.

However, what is similar in these movements is their rejection of the long-held Renaissance tradition. This tradition was derided as ‘illusionism’; it was false to the world and to human feeling. There was a search for art that was created outside this tradition. Primitivism would become an important influence for artists during this time because it offered another way of viewing the world. Primitivism was felt to be untainted by rational control and therefore depicting a truer expression of emotional life.

This dispelling of illusionism was a major force felt within modernist art. Artists were now looking for the genuine in their artwork. They felt it was their job to show the public that the canvas was two-dimensional and that illusionism was not required to provoke thought and beauty. For example, the early abstractions of Kandinsky were an effort to show that beauty could be evoked by non-objective line and color.

After the First World War, there was a pessimism that permeated western culture. That a culture founded on rationality and progress could lead to such devastation. The formation of Dadaism was a symbol of this pessimistic outlook; they wanted to do away with any kind of meaning in art. However, the inherent nihilism created too much tension for the group to stabilize and most of its members would turn to Surrealism. Surrealism was influenced by the new theories of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. They believed that the tensions in culture could be cured if the individual could integrate the conscious and unconscious mind.

Modernist Art: The Established Visual Language

Modernism began to stagnate in Europe due to the rise of Fascism and Communism. Authoritative control stifled creativity, leading many to migrate to the U.S. in order to continue their practices. New York would become the last seed of modernist art with the Abstract Expressionists forming in the 1950s. They took much from these emigres and from the earlier modernist art beginning to be showcased in the U.S.

It was clear by the 1960s that modernist art had established a visual language to reflect the realities of modernity. If modernist art appears difficult to understand, visually, that is because modernity is fraught with contradictions, and such a variety of experience, that it is difficult to wholly comprehend. Modernist art was searching for creative forms that would visualize the experience of being modern and we can now appreciate their boldness. We may, now, be able to gaze at the way geometry intersects and find beauty in it; we may inspect the objects around us a little closer and see that their form isn’t so simple.