The contemporary artist Mona Hatoum explores topics like political conflicts, displacement, and defamiliarization in her work. By transforming familiar, ordinary objects into works that seem foreign or threatening, her art reflects the complex relationship between individuals, their bodies, and the world that surrounds them. Here’s an introduction to how Mona Hatoum turns everyday items such as kitchen utensils, light bulbs, and human hair into artworks that evoke a feeling of uncanniness and danger.

Who is Mona Hatoum?

Mona Hatoum is a renowned contemporary artist of Palestinian origin, known for her thought-provoking installations and sculptures. Born in Beirut, Lebanon in 1952 as part of a Palestinian family, Hatoum experienced being dislocated early in life. Her family never received Lebanese identity cards, which according to Hatoum was the case for many Palestinians who went into exile in Lebanon after 1948. Her father worked for the British embassy, so she has had a British passport since birth.

After studying graphic design at the Beirut College for Women and working at an advertising agency, Hatoum went to London in 1975. She thought that this was only going to be a temporary visit, but when the civil war broke out in Lebanon she had to stay in London. There, she studied at the Byam Shaw School of Art and the Slade School of Fine Art.

Her experiences as a Palestinian in Lebanon and living in the UK while being separated from her family due to war had a profound influence on her work. The feeling of being dislocated is represented in many of Hatoum’s works.

A significant example of this is her video Measures of Distance which explores the themes of displacement and separation caused by the civil war. It depicts images of Hatoum’s mother showering, which are overlaid with letters and conversations between Mona and her mother.

At the beginning of her career, Hatoum worked mainly as a performance artist focusing on her body. In the late 1980s, she started making sculptures and installations. In many of her pieces, Hatoum uses specific strategies to turn the familiar into the unfamiliar. The human body we think we know so well suddenly appears foreign in her work, while everyday objects become part of a surreal and unsettling environment.

Dangerous Kitchen Utensils

To explore the strategies Mona Hatoum uses to create artworks that seem uncanny, it’s helpful to take a closer look at the word uncanny itself. In his essay The Uncanny, Sigmund Freud examined the meaning of the German word for uncanny which is unheimlich. The word Heim to which heimlich relates means home. Freud wrote that the uncanny is that class of the terrifying that leads back to something long known to us, something that’s very familiar.

The title of Mona Hatoum’s work called Home seems to refer to things that are homely. When we look at the installation, however, we experience something different. It consists of a long wooden table, on which 15 steel kitchen utensils are placed. An electric wire runs through the scene. Light bulbs are placed underneath two sieves and a grater. A software program is responsible for when and at which intensity the light bulbs light up. The table is made inaccessible by steel wires. Ordinary and once-familiar objects appear electrified in Hatoum’s work. The steel wires suggest that the installation is something that the viewer needs to be protected or separated from.

The artist said that she called the piece Home because she saw it as a work that shatters notions of the wholesomeness of the home environment, the household, and the domain where the feminine resides. She also said that she views kitchen utensils as unfamiliar items and that she usually isn’t aware of their intended function. She grew up in a society where women are taught cooking in preparation for marriage, which she rejected.

This feminist approach seems even more apparent in her work Homebound from the year 2000 which features a similarly set table, chairs, a crib, a birdcage, and a toy. The domestic scene is again separated from the viewer through steel wire. The wires seem to suggest a sense of entrapment many women feel regarding their roles as housewives and caretakers.

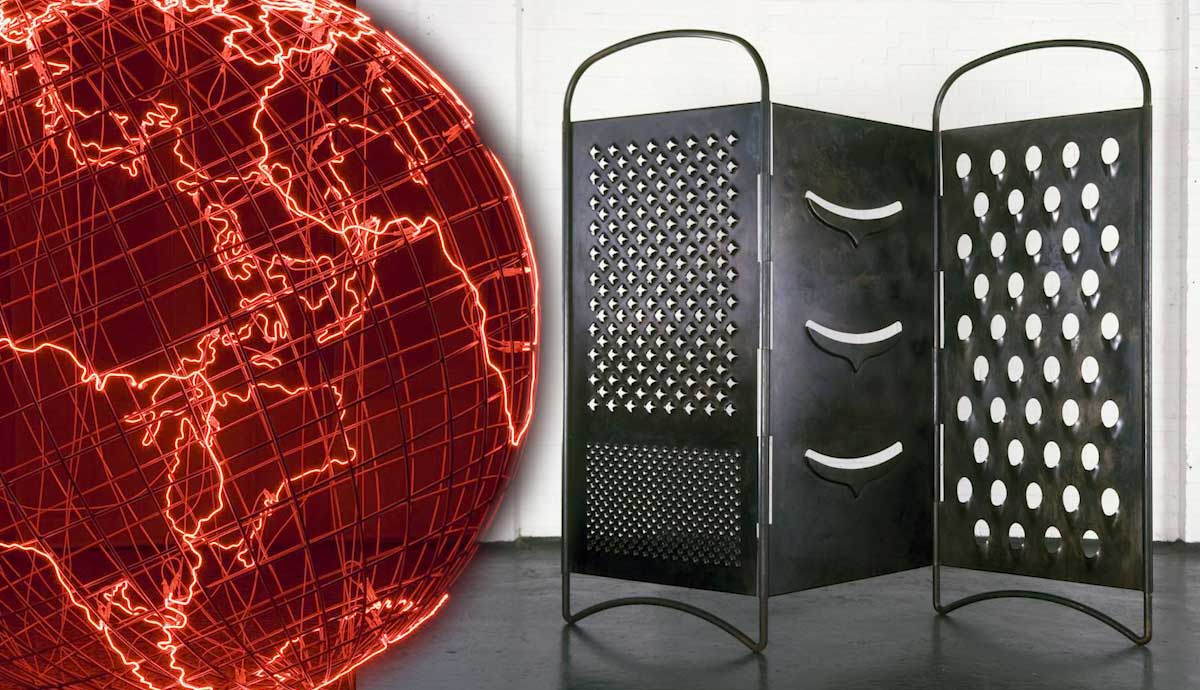

In her work Grater Divide, Hatoum uses a different strategy to defamiliarize a common kitchen utensil. The grater in this work is almost seven feet tall and therefore looks like a possible threat to the human body. Its size makes the object look surreal and potentially life-threatening. With the title Grater Divide, the work also seems to deal with topics like division and separation, which are experiences Hatoum was subjected to in her life.

The Body and Abjection

In Corps étranger Mona Hatoum uses video footage of her own internal organs, recorded during a medical examination, to create large-scale projections that confront viewers with the visceral reality of the body. For the video, Hatoum utilized an endoscopic camera. The footage was shown inside a cylinder-shaped enclosure. The title of the piece, Corps étranger, meaning foreign body, suggests that our bodies, while familiar, can also be seen as foreign entities.

Hatoum’s work challenges preconceived notions of the self and the other, questioning the idea of inside and outside. Even though we think we know our bodies and view them as something familiar, the footage of Hatoum’s work provides a different experience. The artist mentioned how our bodies are still often foreign to us. To illustrate this idea, Hatoum talked about an illness destroying someone’s body without them noticing it.

The effect of Corps étranger can be interpreted by examining Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection. In her book Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Kristeva explores the feelings of disgust and horror we experience when we are confronted with things that defy the boundaries between the self and the other.

This experience of abjection can occur in response to bodily fluids, waste, corpses, bodily processes, and even hair that’s separated from the body. While the blood or the saliva residing inside our and other people’s bodies do not seem disgusting or horrifying to us, this reaction changes as soon as those fluids are not part of the bodies anymore.

The common reaction of disgust when you find hair in your food or in the sink also relates to this concept. Mona Hatoum uses hair that is no longer attached to the body as a material in her art. One example of this is her work Untitled (hair grid with knots 3), which consists of a grid made of human hair on paper. For her installation Interior/Exterior Landscape, Hatoum embroidered a pillow with hair. Another example is Hatoum’s work Keffieh from 1993 to 1999, which consists of a scarf made of cotton fabric and human hair. These pieces all integrate a material that the body discarded, a material which is therefore also made unfamiliar.

Mona Hatoum’s Somber Light Works

Light can evoke pleasant feelings and memories such as the warm sensation of sun rays on skin or the atmosphere in a dark room illuminated by candles. Hatoum’s light works, however, can confront the viewer with a different kind of mood. Her work Light Sentence consists of wire mesh lockers reminiscent of cages and a slow-moving motorized light bulb that casts ominous shadows on the walls of the exhibition space showing the grids of the lockers.

The title alludes to life sentences, while the integration of cage-like objects deals with themes like imprisonment and confinement. Hatoum said that the constant movement of the shadows causes an unsettling sensation. She described the feeling as a sense of instability and restlessness, something that she experienced herself. Hatoum also said that the work is a statement about institutional violence and surveillance in Western countries.

Her work Current Disturbance is also connected to the theme of imprisonment. It consists of similar cages made of wood and wire mesh with light bulbs inside. The light bulbs flicker in an irregular pattern, accompanied by an electrical sound. Since Hatoum made the installation in San Francisco, she assumed that viewers there thought of prison when they saw it because of Alcatraz.

Mona Hatoum’s work Hot Spot III displays a globe with the continents mapped through red neon lights. The work’s title and red lights show how the whole world is an area of conflict. The artist said that she created the first version of the piece in 2006. At the time, it seemed to her that the ongoing conflict was no longer limited to specific regions in the Middle East but was instead affecting the whole world. The bright red color of the lights seems to represent a feeling of danger and urgency.