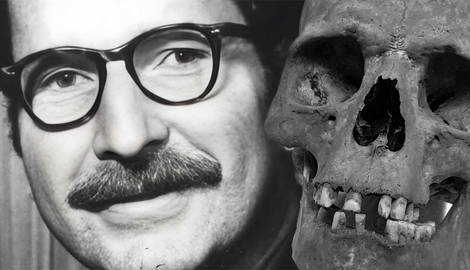

In his Pulitzer Prize winning book “The denial of death,” Ernest Becker postulated that our social and cultural existence is based on avoiding our biological reality, on transcending it with symbols that can live long after we’re gone. Central to his work are the notions of death, heroism, anality, transcendence, and the world as it is. These are the ideas we will explore in this article. These notions are all connected to each other and build an interactive system in Becker’s work.

1. Ernest Becker on the Notion of Heroism

Becker makes an astonishing claim: all cultures and societies are symbolic fields, structures of roles and behavior which serve as the background on top of which our inherent need for heroism can unfold. Through heroism, we deny death and our own impermanence. It allows us to transcend time and the fleeting nature of life.

“…each cultural system is a dramatization of earthly heroics; each system cuts out roles for performances of various degrees of heroism: from the “high” heroism of a Churchill, a Mao, or a Buddha to the “low” heroism of the coal miner, the peasant, the simple priest; the plain, every day, earthy heroism wrought by gnarled working hands guiding a family through hunger and disease.”

The notion of the hero is the central mode of being in the world. The world is a theatre of heroism where the actor tries to gain a feeling of unshakable meaningfulness, a notion of his own cosmic uniqueness. Fundamentally, heroism is one of the only acts which reaches down into our human nature and brings it to life. This is because, according to Becker, it is based on narcissism, the child’s need for self-esteem, the drive to be distinguished. Every society is structured like a religion, even if it declares itself officially secular, the religion being that of heroism and self-transcendence, which permeates all our aspirations within its confines.

Becker argues that everything, our name, our ego, is given to us by signs outside of ourselves, by alien powers with which we identify and manufacture our self. This is why humans feel like they have no authority in the world; they’re not brave. Heroism doesn’t spring from genuine curiosity but from a drive to conceal our own decaying, finite existence, to live forever amongst symbols.

2. Culture as an Antidote to Death

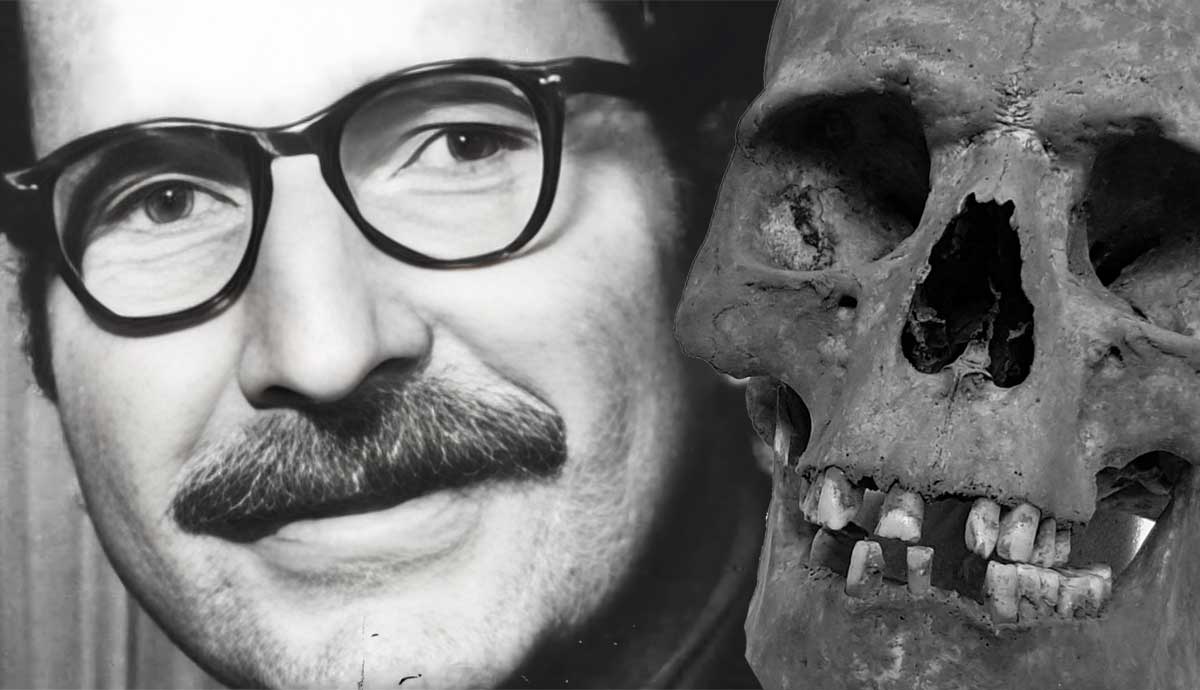

Heroism is nothing but the very negation of death, human mortality, and biological limits. Man is split in two. He has a dreadful awareness of his uniqueness which reaches towards the transcendental; yet his feet stumble on the earthly ground which will soon claim him, footsteps erased by the passage of time. Man is a contradiction. We’re the only animal burdened with the knowledge of its own finitude. We’re crawling beings, gasping for air on top of a pile of corpses, tearing through the flesh of the Other to fend off our inevitable annihilation for just a little bit longer.

Heroism is the symmetrical negation of death. The terror of death haunts our every living moment. We know that everything we do will be undone, and every step we take will be wiped out. The notion of anality expresses our physical finitude, while death signifies our finitude in time. Trapped within the confines of space-time, man turns his head towards the sky, longing for ways in which his existence can manage to leave a mark after he is gone. Split into the symbolic and the material biological reality of its being, man uses the first to conceal the latter. Great buildings, history, culture, monuments, everything we do is to assure ourselves of our own non-temporality and spatiality. Our culture tells us that with the right act of heroism, our name will be crystallized in the flow of time, unmovable, forever displaying our unique existence. This explains our passionate protection of “classic” works of art, literature, or film.

3. Anality, the Body, and Decay

According to Becker, this dualism is expressed most clearly in anality. The child first discovers through anality that the body has demands and functions that it needs to perform, regardless of whether he likes it or not. He learns that his body is a weird, strange creature that functions according to its own rules. He is estranged by it. His anus represents the fact that he is nothing but a body that tears and excrements worldly bodies in order to keep itself alive. In the eyes of nature, he is not a self but a thing.

“The anus and its incomprehensible, repulsive product represents not only physical determinism and boundness, but the fate as well of all that is physical: decay and death.”

Becker gives some examples from Kubrick’s movies to support his point. In “2001: a Space Odyssey,” man’s leap into space is closely related to our ape-like past, and is accompanied by the music of Strauss; and in “Clockwork Orange,” the main character rapes and enacts violence while Beethoven plays in the background. All of our culture, all our transcendental symbols, serve precisely to conceal our animality, to take us beyond it.

Culture is a protest against natural reality, a denial of the human condition of death. Another example of this tendency can be seen in the myths that surround leading figures, such as the North Korean authorities’ claim that Kim Jong-un doesn’t defecate or urinate. Our own excrements remind us from our fatal futility and fleetingness. We want to create an aura that transcends our biological limits, we need to be more than the totality of our biological processes and chemical reactions. It would be unbearable to experience yourself in your full constraints, caught in the net of time, unable to escape the flow of history. Man needs to rise above what he is. He needs to deny the physical. Faced with this fate, how could this animal survive if he did not invent the permanence of the heroic?

4. Coping with the World as It is

The world as it is is too much for us to be able to cope with it. It tells no story, it makes no point, it has no balance, no symmetry, no narrative, no chronology; it signifies nothing. A tendency arises in us to cut back on life, to cut back in this intensity in order for us to be able to deal with it. By the time we leave childhood, Becker argues that we already have learned to conceal raw reality through symbols that function like an airbag softening the brutal blow of reality. People often remember feeling everything with a higher intensity during their childhood. Due to repetition, one might get used to certain things which no longer invoke the same intensity.

Becker tells us that this function is crucial to our own continued existence and is a coping mechanism developed through symbols rather than a natural function of the senses. We need to move through the world with a sense of detachment from it, with a sense of direction that could be easily undermined if we allow the world to come as it is.

“We can’t keep gaping with our heart in our mouth, greedily sucking up with our eyes everything great and powerful that strikes us”

Animals are endowed with instincts that move them automatically in order to respond to outside stimuli. All else is ignored, or more precisely, not even perceived. They live in the silver slice of reality and occupy a territory of neurological and chemical reactions. Man, on the other hand, isn’t confined to a territory within a slice of time. He lives everywhere at all times. He sees his body as a problem to be explained. He sees not only his material body this way but his mental self as well. He is incompressible to himself. Why is he here? What is he supposed to do? The universe remains mute to these calls. Becker calls man, “A god with an anus,” transcendent and stuck, limitless and bound, a walking contradiction.

5. Ernest Becker on Transcendence

Man is caught between the freedom of his ego and the fate of his body. There’s a dissonance between the mind’s unlimited energy and need for transcendence and the body’s incapability of offering such a transcendence. On some level, this is a universal experience. We try to transcend our bodies in all sorts of ways.

One way of striving for transcendence is through sex or masturbation, where it is achieved by making sexuality purely personal, controlling our body precisely to relieve it from determinism. Even this doesn’t always work. Our biology never fails to catch up with us. Schopenhauer called the post-orgasmic moment “the devil’s laughter.” That’s the moment we realize that we have been deluding ourselves, that we are slaves to our own biological imperatives, which couldn’t care less about our happiness or about our notions of transcendence. The body gives us the idea of a certain distance from it only for us to further propel its own goals. By attempting to negate the body, we simply end up affirming it even more.

According to Becker, the way to achieve maturity is to sublimate the individual’s way of transcending his own body into the rest of the social community. Freud asserts something similar: man can paradoxically transcend himself by affirming his non-transcendence, by accepting the reality of his own condition as a biological entity.