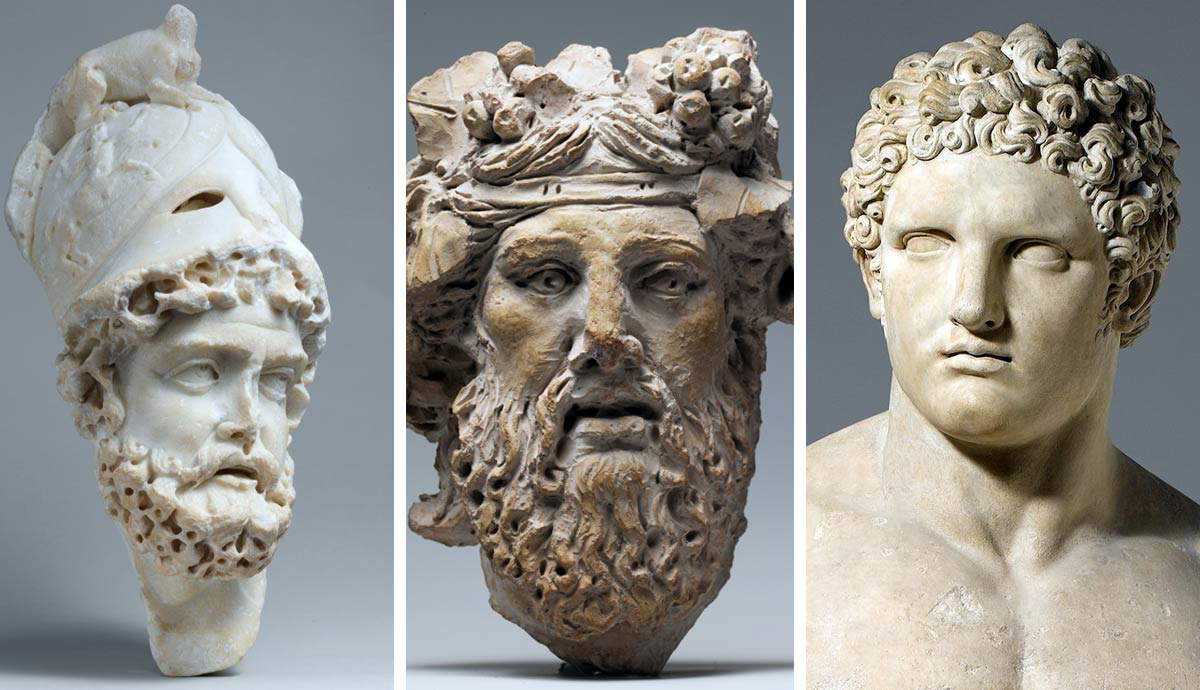

Poseidon was the brother of Zeus and Hades, and one of the primary deities in the Olympian pantheon. He had a place with the other gods atop Mt. Olympus, but he mainly stayed within his domain in the seas, where he was said to live in palaces under the water. Although today he is most recognized as a god of the sea, Poseidon also possessed a close association with the earth. 8th century BCE poet Hesiod starts his Theogony with an invocation to the Muses, and he mentions Poseidon as “he who shakes the earth and holds it.” He is also closely associated with horses, and much of his iconography shows him riding a chariot.

He was worshipped throughout the Greek world and his temples were commonly found near bodies of water. The most important sites of worship were in Corinth, where the Isthmian Games that were dedicated to the god took place; Helike in Achaea, and Onchestos in Boeotia.

1. Birth of Poseidon

Poseidon was born to the Titan gods Kronos and Rhea and was one of six children. Like all his siblings save Zeus, he was swallowed by his father, who feared that one of his children would overthrow him just as he overthrew his own father, Ouranos. Due to Gaia’s intervention, Kronos was made to regurgitate his children.

The 2nd century CE author Pausanias describes another account in his Description of Greece that differs from the above. During his travels through Arcadia, the author came to a spring the locals called Lamb, and the locals recounted to him the story that when Rhea gave birth to Poseidon, she laid him in a flock of lambs that grazed around the spring. When Kronos came looking to devour his newborn son, she told him that she had given birth to a horse and gave him a foal to swallow instead. Thus, like Zeus, Poseidon was also spared from being eaten.

2. Titanomachy

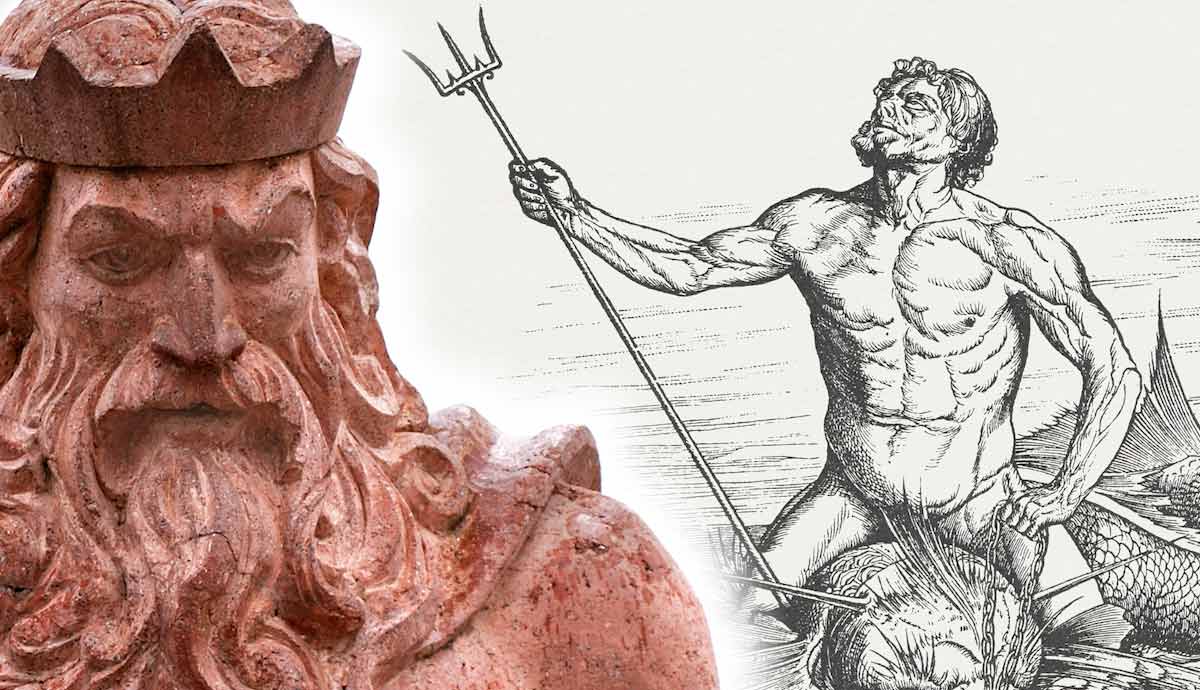

Poseidon joined Zeus and his siblings to overthrow their father in a ten-year-long battle called the Titanomachy. He helped free the Cyclopes from Tartaros and was given his signature trident as a gift. Hesiod wrote in his Theogony that after overthrowing Kronos, Poseidon and the other Olympian gods named Zeus as ruler of the cosmos, and he assigned to each of them their portion of the cosmos, giving Poseidon the seas (Hesiod, 881-885).

Yet in Homer’s Iliad, which was composed near the same time as the Theogony, Poseidon himself contradicts this. When Zeus commanded the god to stop intervening in the war, Poseidon rails against him.

“The world was split three ways. Each received his realm.

When we shook the lots I drew the sea, my foaming eternal home,

and Hades drew the land of the dead engulfed in haze and night

and Zeus drew the heavens, the clouds and the high clear sky,

but the earth and Olympus heights are common to us all.”

(Homer, 15.226-230).

3. Opposition to Zeus

Recounted in a regrettably short passage in Homer’s Iliad, early in Zeus’s reign, Poseidon conspired with Hera and Athena to overthrow him. They chained him up and would have succeeded in their coup were it not for Thetis, an Olympian goddess and mother of Achilles. She enlisted the help of Briareus, one of the hundred-armed and fifty-headed giants who aided Poseidon in overthrowing his father. The giant sat down beside Zeus and his mere presence struck terror into the conspirators.

“That day the Olympians tried to chain him down,

Hera, Poseidon lord of the sea, and Pallas Athena-

You [Thetis] rushed to Zeus, dear Goddess, broke those chains,

Quickly ordered the hundred-hander to steep Olympus,

That monster whom the immortals call Briareus

But every mortal calls the Sea-god’s [Pontus] son, Aegaeon,

Though he’s stronger than his father. Down he sat,

Flanking Cronus’ son, gargantuan in the glory of it all,

And the blessed gods were struck with terror then,

They stopped shackling Zeus.”

(Homer, 1.474-483)

The passage names three gods in particular, yet later in the Iliad, it becomes clear that Apollo also participated.

4. Service at Troy

As punishment for their attempt to overthrow Zeus, Poseidon and Apollo were made to serve the king of Troy, Laomedon, for a year at a fixed wage. Apollo acted as shepherd to the king’s flock, and Poseidon built massive ashlar walls around the city to make it impregnable, but when their service was over and it was time to pay, the king refused. He threatened to bind them up and sell them off as slaves and even to cut off their ears with an axe.

In response, Apollo sent a plague, and Poseidon flooded the plains, then sent a sea monster to terrorize the inhabitants. It is this sea monster that Herakles killed to save the king’s daughter after completing his ninth labor. As repayment, Herakles asked for the mares that Zeus had once given to the founding king of Troy as compensation for the abduction of his son, Ganymede. Laomedon agreed, but the subtlety of the gods’ punishment was lost on him, for he cheated Herakles too (Apollodorus, 2nd c. CE, p.79).

5. Minos and the Bull

Minos was the son of Europa and Zeus. After her abduction to Crete, his mother married King Asterios. When the king died without any children, Minos sought to become the king but met with opposition. He claimed that he had the blessing of the gods to rule, and to prove it, he claimed that whatever he prayed for would come to pass. During a sacrifice to Poseidon, Minos prayed that a bull would appear from the water and promised to sacrifice it when it did. Poseidon heard his prayer and sent up a magnificent bull from the sea. Minos became the king of Crete, but he didn’t sacrifice the bull. Instead, he sent it away to his own herds and sacrificed a different one.

But the god was not fooled. In his anger, Poseidon turned the bull savage and also instilled in Minos’ wife Pasiphae a lust for the animal. She contracted the architect Daedalos to build a wooden cow for her that she could then climb inside. Mistaking the contraption for a genuine cow, the bull mounted it. Pasiphae became pregnant and gave birth to the Minotaur (Apollodorus, 1997, pp.97-98).

6. Contest With Athena

When the gods were still claiming lands for themselves where they’d be worshiped, Poseidon landed in Attica, then called Acte, and laid claim to a city called Cecropia. He struck his trident into the ground, scarring the rock and creating a saltwater well. Athena then came to the city and also claimed it as her own by planting an olive tree.

Naturally, the two of them came into conflict and Zeus had to intervene, calling on the other Olympians to help settle the matter. The city went to Athena, and she renamed it Athens after herself. Poseidon was furious at his loss, so in retaliation, he flooded the Thriasian Plains and submerged the entire land of Attica under the sea (Apollodorus, 1997, p.130).

7. Contest With Helios

Athena wasn’t the only god that Poseidon disputed with for cities. He also claimed the city of Corinth and was opposed by Helios. This contest was arbitrated by Briareus, who gave the acropolis of Corinth to Helios and the Isthmus to Poseidon. The sea god must have been satisfied with the result, since he didn’t flood the land like he did in Attica. The Isthmian Games, an athletic contest like the Olympic Games, were hosted there and celebrated in Poseidon’s honor.

8. Medusa

Medusa was one of the Gorgons, three sisters born to the sea gods Phorcys and Ceto. They are commonly depicted as winged women with snakes for hair and a terrifying grimace. Two of the Gorgons were immortal, but Medusa was different from her sisters in that she was mortal. She caught the eye of Poseidon, and in Hesiod’s Theogony we are told that in a somewhat off-handed fashion, Poseidon “lay down with her among the flowers of spring in a soft meadow” (Hesiod, 1973, p.32).

Ovid recounts another version in his Metamorphoses. Medusa was once a mortal woman with many suitors and beautiful hair. Poseidon then raped her inside Athena’s temple. As a virgin goddess, Athena was deeply offended, and as is often the case with Greek mythology, mortals suffer the consequences. She turned Medusa’s beautiful hair into snakes and made it so anyone who looked upon her turned to stone (Ovid, p.156).

9. Iliad

During the last few weeks of the Trojan War, Zeus had forbidden the gods from interfering, yet Poseidon, like the other Olympians, still meddled heavily. He took the side of the Greeks because he was still angry with the Trojans for how the past king, Laomedon, treated him. His aid mainly took the form of moral support, rallying the men to fight or filling them with confidence and vigor.

During a notable battle where the Trojans had pushed the Greeks back to their ships, Zeus felt confident that no immortals would meddle, so he turned his gaze away. Poseidon took this opportunity to rally the Greeks. He appeared to them as the prophet Calchas, going to Greater and Little Ajax first to inspire them to fight and hold back Hector’s advance. In a somewhat tongue-in-cheek fashion, he says to them:

“[…] if only a god could make you

stand fast yourselves, tense with all your power,

and command the rest of your men to stand fast too-

then you could hurl him back from the deep-sea ships,

hard as he hurls against you, even if Zeus himself

impels the madman on.” (Homer, 1990, 13.68-70)

With this speech, Poseidon strikes them with his scepter and grants them courage and strength. He then sped away and roused the rest of the Greeks to take up arms and fight. Hera watched the battle with interest and devised a plan to put Zeus to sleep. Poseidon was then able to openly affect the battle, leading the armies of the Greeks from the head and clashing with Hector. When Zeus awoke, he threatened Poseidon to leave the fighting, and the god of earthquakes begrudgingly complied.

10. Odyssey

The Odyssey recounts the adventures of the titular hero Odysseus during his return journey from Troy. In the epic, Poseidon is the main antagonizing force that keeps Odysseus from getting home, waylaying him for ten years.

The hero incurred Poseidon’s wrath when he and his crew landed on an island inhabited by Polyphemus, Poseidon’s son. Polyphemus was a man-eating Cyclops and had trapped Odysseus and his men in a cave by blocking the exit with a massive stone. He then proceeded to eat them one by one. In order to escape, Odysseus gave the Cyclops wine and got him drunk. Then, he waited until he was asleep before stabbing him in the eye with a stake of olive wood.

When the hero escaped, Polyphemus prayed to Poseidon that Odysseus never reach his home, or if it’s his fate to return, then to get there late, losing all of his men and ships and finding trouble in his own house. Poseidon would answer his son’s prayer, sending storms and monsters to harass Odysseus every step of the journey.

The god’s hand can also be seen in more subtle ways in many of the misfortunes that befall the Greek hero. Soon after leaving the island of the Cyclopes, he went to Aeolia, where King Aeolus gifted Odysseus a bag of winds to speed his return home. But Odysseus didn’t tell his men the contents of the bag, and when they were within sight of home, Poseidon made him fall asleep, allowing for his men to grow curious and open the bag. The winds escaped and blasted the ships back to Aeolia.

In another episode, Odysseus and his men come to the island of Thrinacia, where the cattle of the sun god Helios were pastured. Odysseus remembered a warning he received from the goddess Circe, that should anyone eat the cattle of the Sun, he would suffer the very fate that Polyphemus prayed for. His crew insisted on landing there, so Odysseus made them swear not to eat the cattle. They landed on the island, but strong winds kept them there for a month, and they ran out of provisions.

At this point, Odysseus knew that some god was against him, though he didn’t know which one. He went off to pray to the gods for help, but again, he was stricken with sleep. While Poseidon was not expressly named as being the perpetrator, none of the other Olympians had a motive to waylay the Greek hero. With their captain asleep, Odysseus’ crew ate some of the cattle. The sun god Helios complained to Zeus, who threw down a lightning bolt and destroyed the rest of the ships.

Odysseus eventually made it home with the help of the Phaecians, who provided him with a ship. Poseidon’s anger didn’t subside, however, and he turned his wrath onto the Phaecians. He waited until their ship was within sight of their city and then turned it to stone (Murgatroyd, 2015).

References

Apollodorus. (1st or 2nd century CE). The Library of Greek Mythology (R. Hard, trans). Oxford University Press, 1997

Hesiod. (8th century BCE). Theogony and Works and Days (D. Wender, trans). Penguin Group, 1973

Homer. (8th century BCE). The Iliad (R. Fagles, trans). Penguin Books USA Inc., 1990

Murgatroyd, P. (2015). The Wrath of Poseidon. The Classical Quarterly, 65(2), 444–448

Ovid. (43 BCE-17 CE or 18 CE). Metamorphoses (C. Martin, trans). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2005