The American photographer Nan Goldin was born in 1953 in Washington, D.C. Her sister died by suicide when Goldin was 11 years old. She left home a few years after that and attended the alternative Satya Community School where she became the school photographer. At this school, she also met fellow photographer David Armstrong. From 1974, she attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. One of Nan’s most famous works is the series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency which captures intimate moments of her life. Her works often depict themes like love, sexuality, loss, obsession, violence, and friendship. Despite the personal nature of her work, Nan Goldin’s photography also deals with many political issues.

***Trigger warning: abuse, violence, assault***

1. Nan Goldin’s Nan one month after being battered

The work Nan one month after being battered is part of her The Ballad of Sexual Dependency series. The series revolves around her and her friends’ relationships, drug use, parties, sex, love, and maybe most of all dependency, as the title suggests. Goldin’s aim was to depict her life, but not in a glamorizing way. The series deals with what Goldin perceived as an ambiguous relationship between heterosexual couples characterized by incompatibility and dependency. She voiced her concern about the irreconcilability of men and women and described them as seeming to be from different planets. Despite this incompatibility, Goldin observed an intense need for coupling between them, which also exists in abusive and destructive relationships.

Nan one month after being battered is one of the artist’s most famous works. The photo and its title refer to Goldin being severely physically abused by her boyfriend Brian. Goldin described their relationship as dominated by jealous passion, sexual obsession, and interdependence. Brian and Goldin were together for several years, so he is often depicted in her photographs. In 1984, when they stayed at a pension in Berlin, Brian started to beat her. The injuries were so severe that Goldin almost lost an eye.

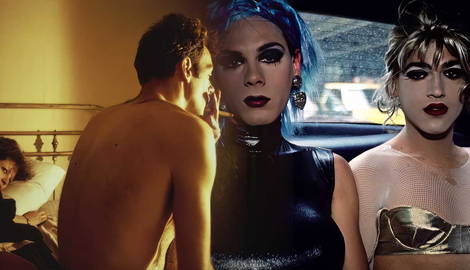

2. Nan and Brian in Bed, New York City

Even though Nan one month after being battered was made weeks after the assault, the clearly visible injuries show the extent of the physical trauma. Her face is bruised and her left eye is bloodshot and swollen. Brian also burned Goldin’s journals. The artist recalled that even though some people knew about the abusive aspects of their relationship, no one came to help her. One friend, however, helped her go to a hospital where her eye was treated when Goldin got back to the United States.

Nan Goldin’s work Nan and Brian in Bed depicts the complicated nature not only of abusive relationships but relationships in general. With Brian looking away from Goldin while smoking a cigarette, her equivocal facial expression can be read as both yearning and restrained, showing admiration and desire, but also fear and estrangement. The photo was the cover of the book version of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. It can be seen as an illustration of what Goldin described as the struggle between autonomy and dependency.

Both photographs are not only depictions of deeply personal and intimate moments in Goldin’s life, but they also serve as representations of abusive relationships. By publishing photos with such a shocking and personal nature, the issue of abuse in relationships is no longer just a private but also a public matter. Photos like Goldin’s draw attention to the subject and might inspire political action that helps victims of abuse.

3. Jimmy Paulette after the parade

In many of her photographs, Goldin represents members and issues of the LGBTQIA+ community. In 1972, Goldin started to photograph drag queens and developed a fascination with them. One example of these early works by Goldin is the black-and-white photograph Ivy wearing a fall, Boston from 1973. She worshiped them and their friendship was an important part of her life. The artist took photos at a drag bar in Boston called The Other Side, which is the title of Goldin’s third published book. She wanted to honor their beauty without unmasking them and said that she saw them as a third gender that made more sense than either of the other two. Nan Goldin was compared to photographer Diane Arbus, but Goldin said that the drag queens she knew hated Arbus since she stripped them and showed them as men.

In the 90s, Nan Goldin met another group of drag queens in New York and started to photograph them. Since her work often revolved around men and women, their identities, and their relationships with each other, Goldin enjoyed working with people who weren’t as constrained by gender boundaries. Goldin’s work Jimmy Paulette after the parade, NYC, 1991 is an example of the photos she took in New York. The title also alludes to the 1991 Pride Parade in New York.

4. Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a taxi, NYC

One of Goldin’s most famous works Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a taxi, NYC was made on the way to the Pride Parade. Jimmy Paulette is wearing the same make-up, ripped mesh top, and golden bustier as in the work Jimmy Paulette after the parade, NYC, 1991. Misty was also photographed by Goldin several times. The works are not just photos of the artist’s private life, her friends, and people she personally admired and loved. By referencing the Gay Pride Parade, Goldin who identifies as bisexual also draws attention to broader political issues concerning the LGBTQIA+ community and the LGBT rights movement.

During the 1991 Pride Parade, there was a moment of silence for people who died of AIDS. AIDS was another topic that Goldin dealt with in her work. Around 70,000 people participated in the march. Some of them held pink ribbons with the name of a person who died of the illness and with a print saying We Remember.

5. Gotscho Kissing Gilles, Paris, 1993

Nan Goldin’s works often show the lives and relationships of her friends. In some cases, this included showing deaths caused by AIDS. Goldin documented the effects the illness had on her friends and their loved ones. The relationship between Gilles and Gotscho is captured in several of Goldin’s photos. Gotscho Kissing Gilles, Paris shows Gilles in the hospital where he died of AIDS. Other photos by Goldin such as The hallway of Gilles’ hospital, Paris, Gilles in his hospital bed, Paris, and Gilles’ arm, Paris also document the last stages of Gilles’ life. Gilles was the owner of a Paris gallery where Goldin showed her works. He was one of the first people who supported Goldin’s photography.

In an interview with Hili Perlson, Nan Goldin discussed how the image of AIDS changed in the media since the 1980s and 1990s. The artist said that she didn’t just think of her friends as people who were dying of AIDS but rather wanted to show their lives. Her work does not deal with the disease itself, but with, as Goldin put it, the people being lost, in all their complexity.

6. Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding, New York City

Nan Goldin curated a show about AIDS called Witnesses Against Our Vanishing at the Artists Space in New York. It took place from November 16, 1989 – January 6, 1990, which coincided with the time that Goldin’s closest friend, actress, and writer Cookie Mueller died from the disease. Mueller can be seen in many of Nan Goldin’s photographs, like Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding, New York City. Goldin included photos of Mueller’s and Vittorio Scarpati’s marriage in the show Witnesses Against Our Vanishing as well as works showing Mueller with her former lover Sharon. Mueller’s husband died of AIDS before her. Her former lover Sharon took care of her during the final period of her life. Goldin showed Vittorio Scarpati’s funeral in her work Cookie at Vittorio’s Casket, NYC. Later, she also photographed Cookie Mueller in her casket.

7. Cookie at Vittorio’s Casket, NYC by Nan Goldin

Goldin witnessed many people die of AIDS and she talked about suffering from survivor’s guilt. Goldin’s work combines political activism with intimate and personal memories of the people she loved. In the exhibition catalog for the show Witnesses Against Our Vanishing, Goldin wrote about AIDS as both a political and personal issue. She discussed how the illness was used as a tool for sexual repression and emphasized the importance of viewing sexuality in a positive light. Because of the immense loss she and others experienced, Goldin also described the show as a collective memorial. For the exhibition, she asked every artist to contribute a personal piece related to AIDS. The exhibition included works of artists like David Armstrong, Kiki Smith, Vittorio Scarpati, and David Wojnarowicz.