What is the relationship between ‘sense’ and ‘value’ in Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy? This article considers the ways in which Nietzsche’s view set him against the philosophical and religious culture of his time. We will also explore a third concept, that of ‘truth’, and ask how truth relates to ‘sense’ and ‘value’ in Nietzsche’s work, before considering the ‘metalanguage’ objection.

Gilles Deleuze began his study of Nietzsche’s philosophy with the claim that “Nietzsche’s most general project is the introduction of the concepts of sense and value into philosophy”. The relation of these two concepts should inform how we define them in the context of Nietzsche’s philosophy, and equally has an enormous influence over philosophical developments in the 20th century.

Nietzsche on Value and Sense

Deleuze claimed that Nietzsche introduced value into philosophy. Given that Nietzsche was working well after many of the greatest philosophers of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries had published extensive, systematic treatments of ethics, politics and aesthetics (i.e, those areas of philosophy which are normally considered subdisciplines of axiology, or the theory of value), Deleuze’s claim may seem somewhat mysterious at first.

However, these are precisely subdivisions of the pursuit of value – they might be the pursuit of ‘ethical value’ or ‘aesthetic value’, but never value in itself. They never involve asking, as Socrates might have in an early dialogue, ‘what is value’ simpliciter. Implicitly, by doing so, one is dragging the entire notion of value into question.

It is much the same with Nietzsche’s concept of sense. Although it is less controversial to describe Nietzsche as ‘introducing’ it, Deleuze is making the same basic point – that Nietzsche, by introducing focusing on the concept of sense in the broadest possible description, is thereby focusing our attention on something new.

Pairing sense and value together in this way also serves to relate the concept to one another. One of the main pillars of Nietzsche’s enduring philosophical legacy is the way in which he uncovers attempts to make sense of the world which aren’t obviously about value as having a hidden conception of value at their very core.

Because the “submerged” value in many of the theories and beliefs Nietzsche saw others around him hold was Christian and moralizing, Nietzsche’s thought was turned against some of the most fundamental beliefs underpinning European society at the time.

This sense of himself as an individual with the potential to think beyond the confines of social acceptability is one of the things which draws generation after generation of intellectuals back to Nietzsche’s work. As Freud reputedly claimed: “[Nietzsche] had a more penetrating knowledge of himself than any other man who ever lived or was ever likely to live”.

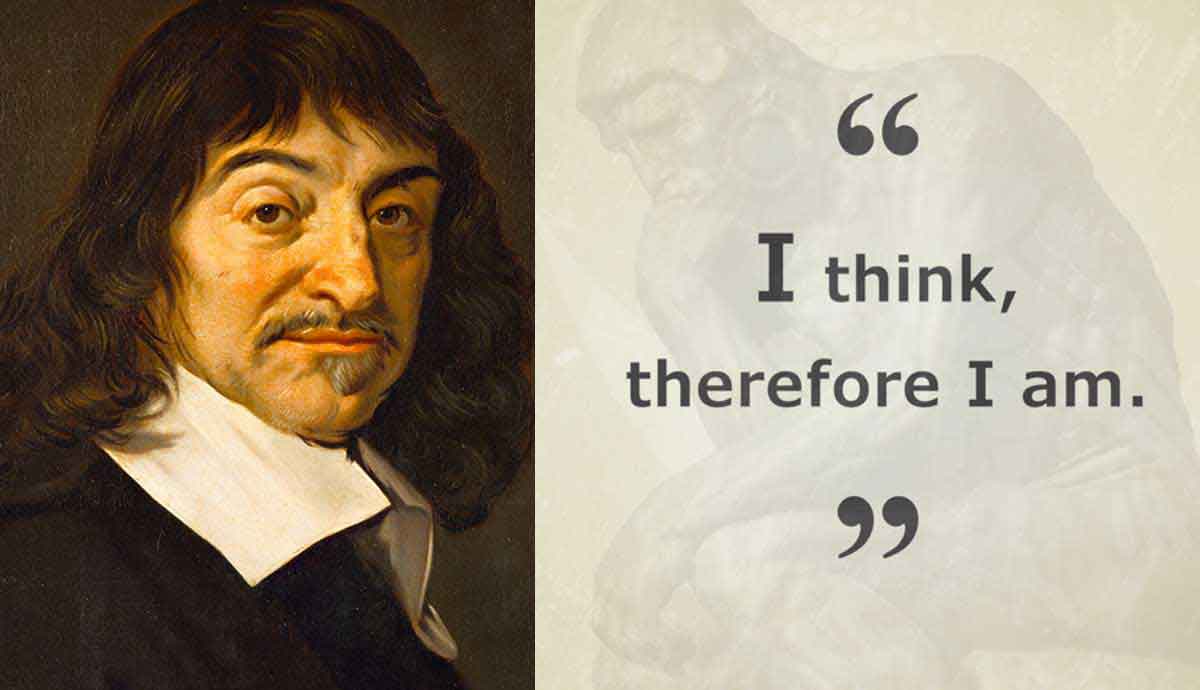

Nietzsche and the Cartesian Tradition

We can frame Nietzsche’s work as, in certain ways, an extension of a long tradition of skeptical enquiry in philosophy. Descartes, as the first of what we call the modern philosophers, posed questions of that which we could not help believing, and wanted to know whether our inability to believe otherwise, ipso facto, meant that such a thing were true.

Some of the questions which Nietzsche poses in Beyond Good and Evil are at one and the same time a natural continuation of Cartesian skepticism, and a complete break from it: “Why should the fact that something is true mean that I do well to believe it?”, “What is it to do well to believe something?”, “Given that we want truth: why do we not prefer untruth? And uncertainty? Even ignorance?”, and finally, “What is truth?”.

Whether Nietzsche’s thought can be seen as a continuation of Descartes’, we should of course note that whereas skepticism is, for Descartes, a strategy to be used and then discarded, Nietzsche’s skepticism is of a far more profound and lasting variety.

Truth, Sense, Value

As Adrian Moore observes, Nietzsche’s approach to truth is intimately connected with his calling the concepts of sense and value into question:

“In a way his critical step back involves asking how sense, in one of its guises, relates to sense in another of its guises. On one way of construing sense, to make sense of things is to arrive at a true conception of them. On another, it is to view them in a way that makes them easier to live with, perhaps even makes them bearable.”

We often draw a fundamental distinction in sensemaking. We give it different names, presenting it at various points as the dichotomy between truth and value, between what is and what ought to be, between reality and possibility. A large part of Nietzsche’s project is attempting to deflate these kinds of dichotomies. Insofar as truth claims itself to be value-neutral, to implicitly assert the dichotomy and place itself on the other side from value, Nietzsche calls truth into question.

The Ideal of Truth

Nietzsche, at certain points, seems to denigrate the concept of truth as an unattainable ideal. However, we should strictly distinguish his doing so (as well as his fixation on the concept of action, the body, power, life and so on) from any sense in which Nietzsche is a parochial figure.

Nietzsche has a profound appreciation for a certain abstract sense of truth as a kind of divine, absolute knowledge which exists above and beyond human existence. He is not immune to this ideal. However, he sees a gulf between this concept of truth, and the kind of ‘truths’ claimed by those around him.

This is partly because Nietzsche approaches truth through the lens of history, specifically the history of its origins, and finds that our concept of truth has evolved from survival strategies:

“Behind all logic and its seeming sovereignty of movement, there are valuations, or to speak more plainly, physiological demands, for the maintenance of a definite mode of life”.

For Nietzsche, this is a fatal problem should we wish to claim anything more of truth than it’s value as a tool of survival, because,

“Things of the highest value must have another, separate origin of their own, – they cannot be derived from this ephemeral, seductive, deceptive, lowly world, from this mad chaos of confusion and desire.”

The Metalanguage Problem

There is a problem which emerges from Nietzsche’s work, which we can call the ‘metalanguage problem’. The problem hinges on those cases in which a philosopher appears to demand that we stop making a certain kind of claim – in Nietzsche’s case, claims about truth which do not pay due attention to questions of value, to questions of practical existence and such.

And yet, to demand that we stop making such a claim (to make a metalinguistic demand on how we speak) appears to break the very rule the philosopher is trying to impose. In other words, is Nietzsche deploying the very concept of truth which he is trying to break away from? If he claims that truth is only useful as a survival strategy and that it is “actually superficial, illusory, counterfeit”, the question then is how one should conceive of this latter claim. Is it true? If Nietzsche is making a claim with the force of truth in the sense which he has just denigrated, then this inconsistency needs some explaining.

Nietzsche on Truth as ‘Superficial, Illusory and Counterfeit’

Just what is it that Nietzsche is claiming here? In claiming that something is ‘superficial, illusory, and counterfeit’, he has not specified precisely what the point of contention is.

As Adrian Moore points out,

“Not believing something need not mean believing the opposite. It may involve having no belief about the matter at all. It may even involve refusing to think in such terms.”

Yet, isn’t Nietzsche speaking in such terms? Really, there seem to be two Nietzsches. On one hand, there is the Nietzsche who is speaking in defense of untruth, of appearance, of value, of everything opposed to the clinical, decontextualized version of truth which the ‘philosophers’ lean on (meaning, primarily, Immanuel Kant and those who have followed him). On the other hand, there is the Nietzsche who is gesturing towards a version of truth not yet realized, a version which requires a total abolition of truth in its present condition:

“Look instead to the lap of being, the everlasting, the hidden God, the ‘thing-in-itself ’ – this is where their ground must be, and nowhere else!”.

If Nietzsche is only seen to prefer the former, then Moore’s defense is clearly sufficient. If it is the latter claim that Nietzsche wishes to make, then we need to go a little further in defining this new version of truth.

Is Nietzsche claiming that philosophy as he finds it indulges in falsehood relative to this almost revelatory version of truth? Or is he claiming that it is merely inconsistent – that it promises what it does not deliver? Does he both wish to favor that which is life-affirming, and yet also claim that it is the very usefulness of the concept of truth that taints it?

To claim that behind truth there are values is not to deny that truth as such is an unsustainable concept. Equally, to claim that no one should talk about things being ‘true’ or ‘false’ any longer isn’t to say that you necessarily drop entirely one’s appreciation of the ideal which motivates the concept.