Amid World War II, President Roosevelt’s articulation of the “Four Freedoms”—speech, worship, from want, and from fear—galvanized American support for intervention. Concurrently, Norman Rockwell, snubbed by government agencies, embarked on a personal mission to depict these ideals in relatable, domestic scenes. His iconic paintings, initially rejected, soon adorned magazines, catalyzing a profound national tour and selling millions in war bonds. Despite initial skepticism, Rockwell’s work endures as quintessential American art, embodying values that transcend time and inspire generations.

“To Sell Goods, We Must Sell Words.”

There was no denying the American people’s distaste for foreign wars. Each resulted in deep divisions among the United States populace. Yet, World War II was supposed to have been different. If President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) learned anything from the First World War, it was to not dismiss the vital importance and power of public opinion and support.

Like President Woodrow Wilson, Roosevelt faced an electorate deeply divided between neutrality and war. And very much like his predecessor, the champion of New Deal policies needed to unite his people behind a concept or idea worth the ultimate sacrifice. For Wilson, it was “democracy,” but the stakes seemed bigger for FDR.

The evils perpetuated by the Germans and Japanese gave the United States government a perfect opportunity to “sell” its people on the idea of a “Good War,” where the contrast between the noble and evil was no less than that between light and darkness in the famed paintings of Italian Baroque artist Caravaggio. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, it was time to start the advertising campaign for war. This time around, it would not be to make the world safe for “democracy.” The American people would fight for “freedom.”

The inter-war period in the United States saw a massive rise in mass production, media, and advertising. Technological advancements resulted in a surplus of consumer goods needed to reach a wider audience. It was no longer about browsing storefronts but about utilizing the rising medium of national newspapers, magazines, and radio.

As famous American historian Eric Foner points out in his book The Story of American Freedom, “‘To sell goods, we must sell words,’ had become a motto of advertisers.”

Advertisements shifted from simply informing about the products to appealing to human emotions, desires for social status, and modernity. “It’s Toasted!” and “Breakfast of Champions,” proclaimed Lucky Strike cigarettes and Wheaties cereal advertisements. Psychology was now used to better understand consumer behavior. Ads portrayed products, beliefs, and conformity as essential for social acceptance and avoidance of being left behind. In order to inspire the reluctant population to pick sides and support the war in Europe, interventionists took cues from consumerism and settled behind “for freedom” as the new slogan that would help the American people “buy” into the idea of war.

Fighting for Four Freedoms

While independent pro-war committees like the Committee to Defend America, Fight for Freedom Committee, and Freedom House used the moniker “freedom” as early as 1940, FDR would be the one to cement the defense of “freedom” as the justification of the US intervention into arguably the most significant conflict the world had ever seen.

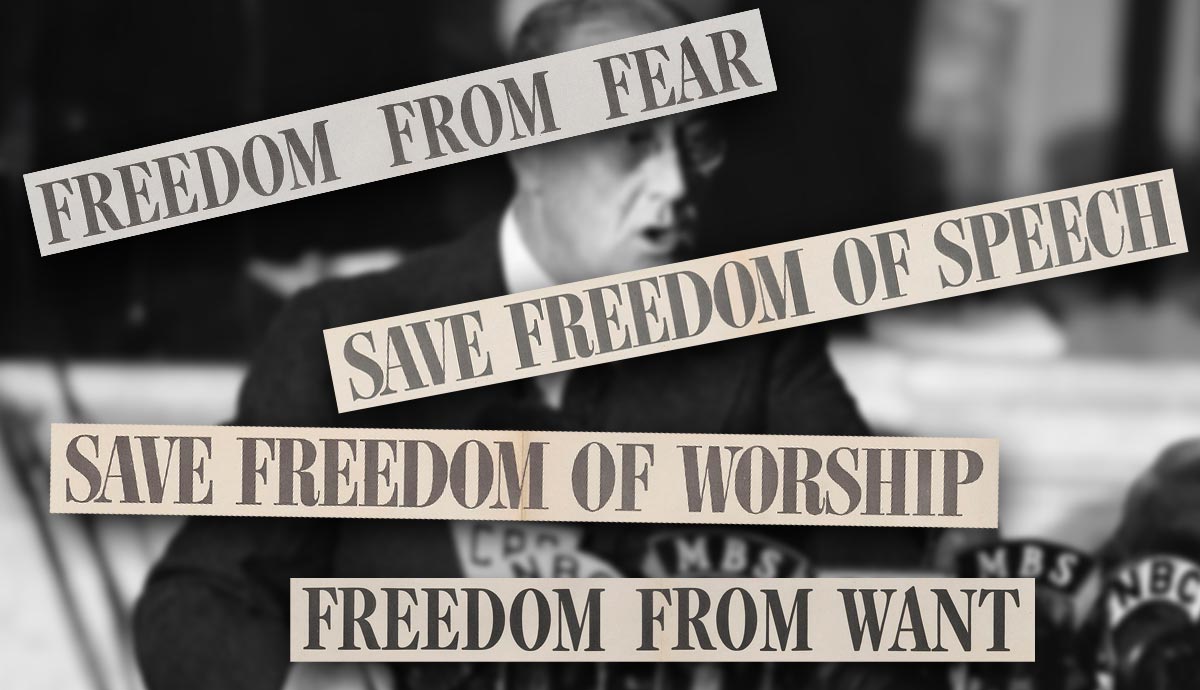

In his State of the Union Address of January 6, 1941, eight months before the US entrance into World War II, Roosevelt presented to the American people a desire for a new world order based on four essential freedoms worth fighting to protect: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear. While the first two were more literal, the latter two translated into freedoms from economic deprivation, poverty, and hunger and the freedom from living in constant fear of violence and oppression.

The speech, later seen as the cornerstone of American democratic ideals, transcended its literal meaning and, like the many great advertisements of the day, appealed to the American people’s emotions—in this case, the sense of duty and honor. Once the US entered the war, FDR often returned to his “Four Freedoms.” In a June 14, 1942 Fireside Chat, one of the thirty radio addresses he gave throughout his presidency, Roosevelt spoke of them as “rights of men of every creed and every race, wherever they live,” adding they symbolized “the crucial difference between ourselves and the enemies we face today.”

The powerful articulation of the “Four Freedoms” resonated deeply with the American public, shifting public opinion toward supporting intervention and serving as a guiding principle behind the willingness for sacrifice. The Americans were on their way toward understanding what they were being asked to fight for, but it would be Norman Rockwell who would make them believe in it.

Rockwell’s Inspiration & Disappointment

Norman Rockwell was already a famous painter when the United States entered World War II in December 1941. The artist’s Saturday Evening Post covers had made him a household name, and his depictions of American life endeared him to the masses who saw themselves in his paintings. Rockwell was not new to war propaganda, having painted popular images for the Post of American soldiers and Boy Scouts during the First World War. Yet, nobody in the government asked Rockwell to contribute when Executive Order 9182 established the United States Office of War Information (OWI) in June 1942.

The agency, directed by the famous news reporter Elmer H. Davis, was responsible for disseminating propaganda to influence the public to favor the war effort and accept the needed sacrifices of rationing and price controls at home. Apart from films, photographs, and radio broadcasts, the OWI used poster campaigns like the one based on the iconic image of J. Howard Miller’s “We Can Do It!” Rosie the Riveter to “sell” the war to the American people.

With the US forces already fighting in the Pacific and now preparing to enter the North African theater of war, Norman Rockwell wanted to paint something inspirational. “I wanted to do something bigger than a war poster,” he stated later, to “make some statement about what the country was fighting for.”

The idea to concentrate his statement painting on Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” came to the artist during an isolated case of insomnia. After tossing and turning in his bed, he randomly thought of Jim Edgerton, a Vermont farmer standing up in a small town hall meeting to protest a tax hike for a new school. Everyone disagreed with the man, and yet they let him speak.

Rockwell wrote years later in his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator (1988), “No one had shouted him down. My gosh, I thought, that’s it. There it is. ‘Freedom of Speech!’”

The excited artist had his idea for a war poster. He would use his Vermont neighbors as models to illustrate the “Four Freedoms.” Like pieces of the puzzle falling into place, the author lay in bed staring at the ceiling at 3:00 a.m., sketching the simple ideas of everyday scenes right in his mind. “Freedom of Speech” would become a New England town meeting, while “Freedom from Want” would be a Thanksgiving dinner.

“Take them out of the noble language of the proclamation and put them in terms everybody can understand,” he thought.

Two days later, with the rough sketches complete, Norman Rockwell was off to Washington to offer his services to the government. The first stop at the office of Robert Patterson, the Undersecretary of War, was unsuccessful. The politician praised the sketches only to tell the artist he was not interested in publishing them at the given time. It was much the same at the next few stops that Rockwell’s friend from the popular Brown and Bigelow calendar company had arranged for him in the capital.

The final offense came at the last meeting of the day courtesy of the head of the art department and war bond campaign at the Office of War Information. After looking through the four prints, the disinterested man looked up at Rockwell. “The last war, you illustrators did the posters,” he said. “This war, we’re going to use fine arts men, real artists.”

Seeing that Rockwell was taken aback and presumably not thinking about the harshness of his words, the OWI man finished with, “If you want to make a contribution to the war effort, you can do some of the pen and ink drawings for the Marine Corps calisthenics manual.” The artist thanked the director for his consideration and offer and promptly refused. It was time for Rockwell to return home; his talents were not needed in Washington.

Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms”

Back in New York, Rockwell shared his disappointment with the trip at a lunch meeting with his employer, Ben Hibbs, the editor at the Saturday Evening Post. To the artist’s surprise, the editor asked to look at the sketches, upon which he quickly shared his excitement.

“Norman, you’ve got to do them for us,” he stated frankly. “Drop everything else and just do the ‘Four Freedoms.’ Don’t bother with Post covers or illustrations.”

Rockwell did not need to be asked twice after the lousy time and rejections he experienced in Washington. For the next six months, the artist locked himself in his studio and began painting the works that would arguably define his career. For Rockwell, it was even more critical that he could finally do his bit and provide the needed context to the sacrifices an entire generation of Americans was being asked to make. Fame, recognition, or legacy were not on his mind.

The process was not easy. Even though Rockwell started by painting Freedom of Speech, which initially inspired the idea for the entire set, it still took him four tries before he felt he had gotten it right. Freedom of Worship took almost two months by itself. Believing that religion was an extremely delicate subject where it was easy to hurt many people’s feelings, the artist struggled with his statement against religious discrimination.

The initial painting of a Catholic priest and an unknown Black man waiting as the Protestant barber finished giving a haircut to a Jewish man seemed too ridiculous. One visit from the editor, who kindly reminded Norman that he did not have indefinite time to submit his paintings, led to an unconscious, spur-of-the-moment act. Rockwell waited for Hibbs to leave, then sat down without much thought and painted Worship from his head without using any models—it is the image we know today.

Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear gave Rockwell little trouble. The artist painted the turkey in the first image on Thanksgiving Day after Mr. and Mrs. Rockwell’s cook, Mrs. Wheaton, had cooked the bird. She was the lady holding the main dish in the final painting. “It was one of the few times I’ve ever eaten the model,” he quipped.

Freedom from Fear, on the other hand, was based on the idea that Americans did not need to worry the same way as Londoners did when putting their children to sleep during the time of the German Blitz on the United Kingdom. The former was especially misunderstood by anybody not American or accustomed to the holiday it depicted, and the latter seemed, even to the artist, to be not strong enough with its message. Rockwell later admitted that these two paintings were his least favorite. The editor of the Post thought along the same lines when, following the war, he only hung Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Worship in his office as a daily source of inspiration.

Legacy of Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms”

The main difference between Norman Rockwell’s interpretation of the Four Freedoms and President Roosevelt’s was that, while the latter presented them with an international focus, the artist made them exclusively domestic in scope. These were images of Americans depicting American ideals, such as small-town meetings and Thanksgiving. This was in contrast with FDR’s vision, where in his speech, he ended the description of each one with “everywhere in the world.”

When the Four Freedoms paintings first appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, they were each accompanied by brief essays emphasizing the values they depicted. While celebrated authors wrote three articles, Freedom from Want fell to an unknown Filipino Poet, Carlos Bulosan. An immigrant who came to the United States at the age of sixteen, Bulosan’s essay added even more depth to Rockwell’s message.

According to Eric Foner, the poet managed to extend the ideas of freedom to Americans still outside the social mainstream, such as migrant workers, cannery laborers, or Black people who were victims of segregation. For them, “freedom meant having enough to eat, sending their children to school, and being able to share the promise and fruits of American life.”

It quickly became apparent that Rockwell’s images and the essays that accompanied them were exactly what the American government did not know they needed to drive home their message of unity behind a common cause.

When the paintings finally appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in early 1943, they debuted not as covers but as inside features. They almost instantly became the best-known and most appreciated paintings of the time.

“Requests to reprint flooded in from other publications,” Rockwell would later write. “Various government agencies and private organizations made millions of reprints and distributed them not only in [America] but all over the world.”

With the early rejections in Washington long in the past and the immediate buzz surrounding Rockwell’s images growing by the day, the Treasury Department asked the artist if he would lend his paintings for a national bond tour. The irony did not escape Norman, who had wanted to do just that when he first visited the capital to offer his services. Ultimately, 1,222,000 people viewed the Four Freedoms in sixteen leading cities, which helped sell $132,992,539 worth of bonds.

Finishing the massive paintings, which measured 44 by 48 inches each, left Rockwell admittedly tired. Instead of going on tour with his creations, the artist returned to doing what he loved best: painting Post covers and working on a new Boy Scouts calendar.

At the time, the illustrations provided exactly what the American people needed: a tangible and relatable interpretation of abstract freedoms. The paintings conveyed the importance of each freedom through such realistic and heartfelt portrayals of everyday American life that they transcended their initial purpose.

Today, Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms continue to endure as symbols of American identity and values. In another great irony, Rockwell, the man who politicians in Washington DC dismissed as simply an illustrator, gave us four paintings that artists and non-artists alike now consider masterpieces of American art that continue to inspire people worldwide.