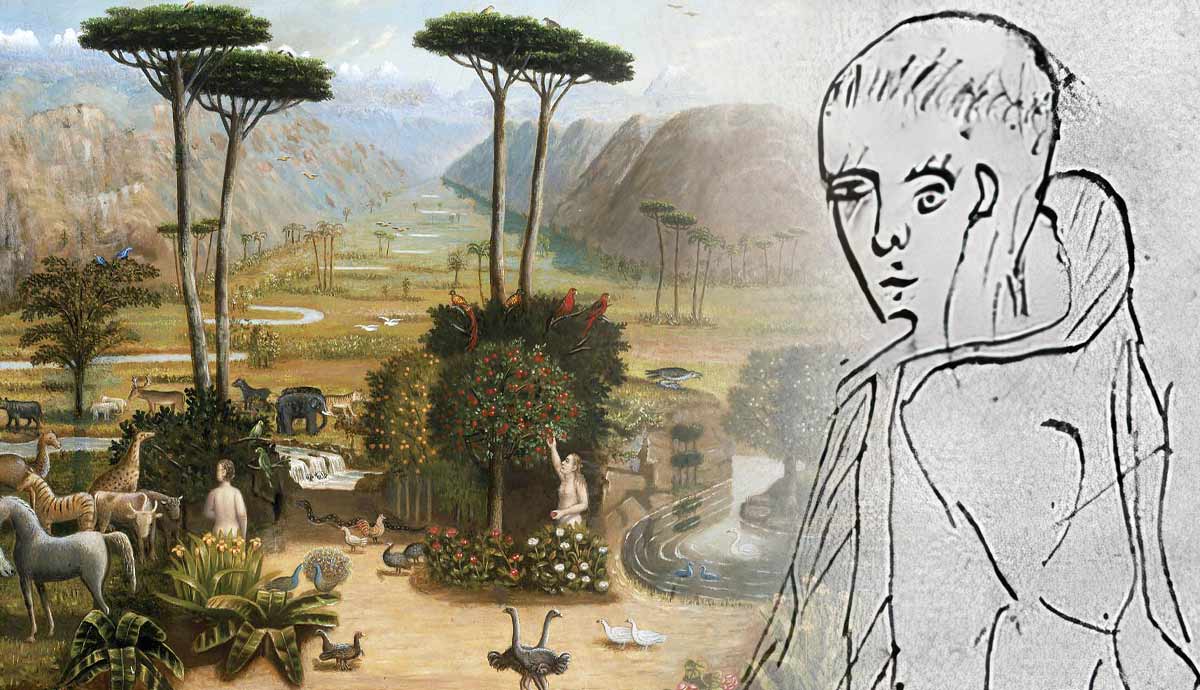

In his quest to trace the form of the perfect Adamic language through which Adam communicated with God in the Garden of Eden—William of Ockham, the English Franciscan friar and scholastic philosopher ventured into the depths of the human mind. There, he unearthed what he believed to be the modern vestige of this sacred vernacular: the universal, mental language that resides within us. This exploration was the foundation for contemporary thinkers—such as Jerry Fodor—to build upon their own theories of mental language.

Introducing: William of Ockham

William of Ockham (c. 1287–1347) was one of the medieval daredevils who questioned the Pope’s political supremacy and the theoretical inconsistencies of his peers. His life was a series of peculiar events, from heresy charges to house arrest and excommunication, and death under unclear circumstances.

Best known for the eponymous principle of Ockham’s Razor, through which philosophers argued in favor of simpler theories and hypotheses in comparison to those with heavier ontological baggage, Ockham’s contribution to the philosophy of language and philosophy of mind inspired the theoretical development of cognitive science in the 20th century. Jerry Fodor’s The Language of Thought Hypothesis (LOT) echoes Ockham’s idea of mental language.

What Is Adamic Language?

The Adamic language marked the Judeo-Christian religious tradition. It was believed that Adam, as the first man, got to name all the creatures in the Garden of Eden by the gift of perfect language that God bestowed upon him. This perfect language captured the true essence of every creature by linking the most adequate or perfect words to such essences.

The Adamic language owed its perfection to its divine origins and represented a single, pure, universal human language. After the destruction of the Tower of Babylon, many imperfect and sullied languages emerged, and these languages are, in fact, our diverse mother tongues. Unequivocal communication in these languages is hard to achieve, and the rules for nomenclature are often unclear. However, philosophers, theologians, and mystics hoped that if they looked deep enough, they would find traces of the one true source, namely the Adamic language. This would, in turn, steer humanity towards divine wisdom and moral purity. The Tower of Babel would be built again, and we would have a profound understanding of each other.

This was the motivation that Ockham shared with other scholastic philosophers and theologians in the Middle Ages when he started to think about the most likely candidate for the perfect Adamic language.

Ockham’s Philosophy of Language

Ockham’s philosophy of language was based on the work in scholastic logic that was Aristotelian to the bone. In his Summa of Logic, Ockham discussed at length signification, one of the core notions in scholastic logic. Signification relates to what a particular term makes us think of.

Ockham thought that there were at least two kinds of signification: primary and secondary. For instance, “cute kittens” signify a clutter of cute kittens. The former signification directly represents the object, while the latter is indirectly linked to the object through a concept or mental image.

For example, “cute” may also signify “cuteness” as a concept but not any particular thing that also happens to be cute. Essentially, this is a psychological relation that grounds supposition.

Supposition is another core notion in scholastic logic and has to do with a reference: how we use terms to refer to objects. Like most medieval logicians, Ockham also distinguished between three types of supposition:

1. Personal supposition: terms stand for objects in the world (“otters” stand for lovely creatures that float around while holding each other’s paws);

2. Simple supposition: terms stand for concepts in mind (“otters” stand for mental images of lovely creatures that float around while holding each other’s paws – thank you, brain);

3. Material supposition: terms are mentioned rather than used (a picture of an otter in front of the designated space for otters in the ZOO).

Given that Ockham was nominalist (meaning he did not believe that there are mind-independent universals like realists do), he emphasized simple suppositions. That is to say, for Ockham, the only universals that exist are universal concepts rather than entities. This is why Ockham’s nominalism is also called conceptualism. Written or spoken terms express these concepts or, better yet, lend their voice.

Ockham’s Philosophy of Mind

Ockham’s views on signification and supposition were ahead of his time because he was among the rare scholars who saw that arguments in the philosophy of language and logic need some sort of psychological or cognitive grounding. In other words, Ockham’s philosophy of mind was introduced to support his more abstract lines of inquiry. The first thing he needed to settle was how to fix the reference—why does the word “otter” refer to a particular otter?

Human beings come equipped with perception. There is a causal relationship between our perception and objects in our environment, and concepts emerge as a byproduct of this relationship.

Ockham tried to offer an analogy to explain the causal impact of objects on our minds. Thus, he invoked cases when owners of medieval taverns put barrel hoops in front of the tavern to convey to locals that the tavern was awash with new wine barrels. The hoop is not the wine itself but transfers the intended meaning. Likewise, the objects in our environment transfer the intended meaning to concepts in our heads. This means that concepts are natural signs for Ockham – they have primary, direct signification based on the acts of perception.

Ockham’s Three Features of Mental Language

Mental language, or mentalese, should consist of all the concepts we could possibly have. According to Ockham, mental language has three key features:

1. It is compositional: complex concepts are created out of simple ones, similar to sentences in a mother tongue created out of words.

2. It is a perfect fit to states of affairs in the real world: unlike any mother tongue, mental language is not subject to imprecisions and equivocations because it corresponds perfectly to objects in the real world, like a

3. It is universal: whereas the mother tongue is relative to a particular ethnic group or geographical region, mental language is shared.

These features suggest that Ockham’s mental language is a candidate for the perfect Adamic language.

Recall that Adamic language was perfect in virtue of revealing the true essence of God’s creation through reference or naming. Unlike imperfect languages that flooded the Earth after the Babylon mayhem, the Adamic language was not liable to imprecisions, incoherencies, or ambiguities like Ockham’s mental language, which was believed to underlie our mother tongues.

The Rebirth of Mental Language in Cognitive Science

During the Early Modern Period and Enlightenment, philosophy turned away from being a servant to theology as in the Middle Ages and became a reference point for science. The Adamic language got its secular version in the form of searching for the ideal logical language that could be used for scientific disputes.

This novel quest sparked the revolution when mathematical logic replaced scholastic logic. It seemed that Ockham’s mental language was rightly forgotten in the junkyard of medieval ideas and has no place in the secular scientific investigation of the world and our place in it.

The 1970s have seen the birth of a new scientific discipline aimed at uncovering the mystery of the human mind, namely cognitive science. From the very beginning, cognitive science was a multidisciplinary endeavor. Constituted and shaped by linguistics, philosophy, psychology, AI research, anthropology, and neurobiology, this scientific discipline had both a firm theoretical foundation and empirical ambitions.

Jerry Fodor’s Contemporary Contribution

One of the pioneers, Jerry Fodor, proposed a “language of thought.” Fodor believed that LOT was the grammar of our minds. Let’s hear it from the Fodor himself:

“If the main line of this book is right, then the language of thought provides the medium for internally representing the psychologically salient aspects of the organism’s environment; to the extent that it is specifiable in this language—and only to that extent—does such information fall under the computational routines that constitute the organisms’ cognitive repertoire.” (1975: 180)

Jargon aside, Fodor wants to say that internal mental representations of sentences are essentially translations into LOT.

Like Ockham’s mental language, LOT has criteria. First, LOT is compositional: its constituents and concepts combine into complex structures according to the rules of mathematical logic. Second, LOT may not correspond to reality directly, but it is part of our “cognitive repertoire” through which we learn about the world by processing information. Third, LOT is universal and innate—everyone has it even though the mentally represented sentences may be in one of the many public languages. Therefore, it makes sense to consider LOT a secular version of Ockham’s mental language.

Finally, the inspiration for LOT and Ockham’s mental language may come from the same implicit assumption—human uniqueness. By searching for the perfect Adamic language, Ockham wanted to reinstate the wisdom of humans, the only creatures given a language by God himself. By introducing LOT, Fodor wanted to scientifically back up the idea that humans are the only ones with a perfectly developed and innate language capacity. Be it as it may, the interesting point is that echoes of the medieval philosophy of language and mind can be traced in contemporary cognitive science.

Watch this video to learn more about Ockham’s Razor:

Further Suggested Reading

- Fodor, J. (1975). The Language of Thought. Thomas Y. Crowell Company.