By the 1820s, Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party began to splinter due to internal divisions. Coupled with the rise of more liberal constitutions in the new states on the American Frontier, a new populist movement for the betterment of the “common man” found its champion, Andrew Jackson. The latter’s charisma and appeal led to the formal establishment of the Democratic Party.

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic Party, one of the two major political parties in the United States, has its roots in the ideologies of two of the more famous Founding Fathers, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. The Democratic-Republican Party of the 1790s was a response to the Federalist Party led by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. While the former championed states’ rights, individual liberties, and an agrarian-based economy, the latter advocated for a strong central government and banking system.

As the Federalist Party weakened after the War of 1812, so did the unifying force that bound the Democratic-Republicans’ different geographical regions (North, South, West). New ambitious figures within the party, such as Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Andrew Jackson, amassed their own following, each with distinct views. The growing divide was most evident between the Northern and Southern states. The industrial North sought protective tariffs and infrastructure improvements, while the rural South prioritized low tariffs and minimal government intervention.

The conflict began during the contentious 1824 election that saw four major candidates emerge from the Democratic-Republican Party, the only political party left. Andrew Jackson won the plurality of the popular vote and electoral votes against John Quincy Adams, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay, but not the majority, hence throwing the decision of the outcome to the House of Representatives. In the controversial “Corrupt Bargain,” Henry Clay pushed through the election of Adams through the House in return for the position of the Speaker of the House.

Feeling cheated and betrayed, Jackson’s supporters, many coming from the rural Western states, saw the bargain as an undemocratic move by the political elite. Jackson became the anti-establishment candidate, a champion of the “common man,” setting the stage for creating a new party.

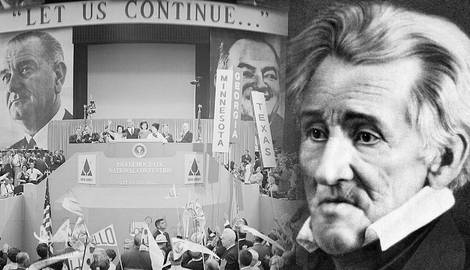

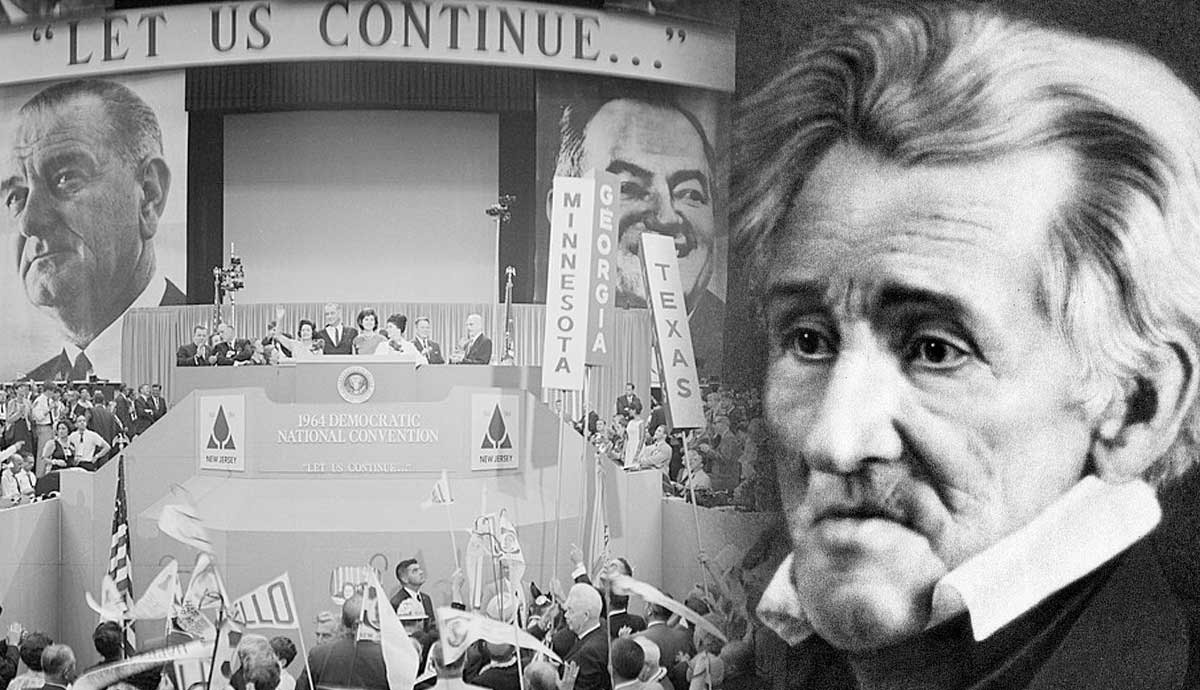

Jacksonian Democracy

Returning in 1828 as a formidable political force that embodied the populist sentiments of many Americans alienated by the political establishment, Jackson’s political power seemed unstoppable. The Tennessean’s appeal lay mainly in his image as the self-made man, a rugged individual, and a staunch advocate for the average American.

Already a national hero from his time in the War of 1812, Jackson now championed the ideas of democracy and individual rights—the same principles once touted by the Democratic-Republicans during the time of Jefferson and Madison. He positioned himself in the new election as a man running against the entrenched interests of Washington, advocating for a government that was more responsive and accountable to the people instead of the political establishment.

The 1828 campaign was for Jackson to call for expanding democratic participation, emphasizing egalitarian themes, and attacking elitist corruption in the federal government. His victory was seen as a triumph of the “common man.” Yet, to many of his supporters, it was more than that. They pointed to it as the beginning of a new political era that celebrated popular sovereignty and the empowerment of ordinary citizens, a movement toward liberating democracy from the clutches of the wealthy and truly democratizing American politics.

These followers of Jackson soon began calling themselves by a new name. They were no longer Democratic-Republicans but simply Democrats. Those in the opposite corner, representing more Northern and Eastern industrial interests, would now be known as the National Republicans.

Creation of the Democratic Party

The Democratic Party was officially named while Jackson was already in the White House but would not become official until 1844. Built on the foundation of Jacksonian principles that emphasized democratic ideals and opposition to centralized power, the new political party advocated individual liberty, economic opportunity, and limited government intervention.

While Jackson’s enemies twisted his name into “jackass” to ridicule him, the new president’s supporters seized on the term as one of endearment, and soon the donkey became the party’s official mascot—although it would not be until the 1870s when cartoonist Thomas Nast officially used the animal to represent the Democrats.

Once in office, Jackson’s Democratic Party agenda focused on reflecting the party’s priorities. The president worked feverishly to dismantle the Second Bank of the United States, which he viewed as an instrument of elite power. He then followed that up by implementing the Indian Removal Act, forcibly relocating Native American tribes to make way for white settlement of the West. While controversial even during Jackson’s time, the actions were meant to expand democracy for the “common man.” The idea lay with the thought that if money were moved from a central bank into state banks, it would be more accessible to the commoners, who could then take out loans to better their social and political standing. Similarly, opening up western lands would presumably bring in more people and expand the population, growing the Democratic electoral base.

Legacy

Another staple of Jacksonian Democracy was the “spoils system” of rewarding political supporters with government jobs, regardless of their qualifications. For the first time, people who could before only dream of voting were now not only granted suffrage rights but actual positions within their local, state, and national government.

For many, the age of American Democracy had finally arrived, and Jefferson’s dream that “all men are created equal” had finally come to fruition. However, the disenfranchised, mainly women, Native Americans, and people of color, as well as the millions of enslaved people, never got to experience it. It would take decades for the party and the nation to make enough progress to begin to see that dream realized.