Socialist realism took many forms: music, literature, sculptures, and film. Here we will analyze the paintings of this era and their unique visual forms. Not to be confused with social realism such as Grant Wood’s famous American Gothic (1930), socialist realism is often similarly naturalistic but it is unique in its political motives. As Boris Iagonson said on socialist realism, it is the “staging of the picture” as it portrays the idealism of socialism as if it was reality.

1. Increase the Productivity of Labour (1927): Yuri Pimenov’s Socialist Realism

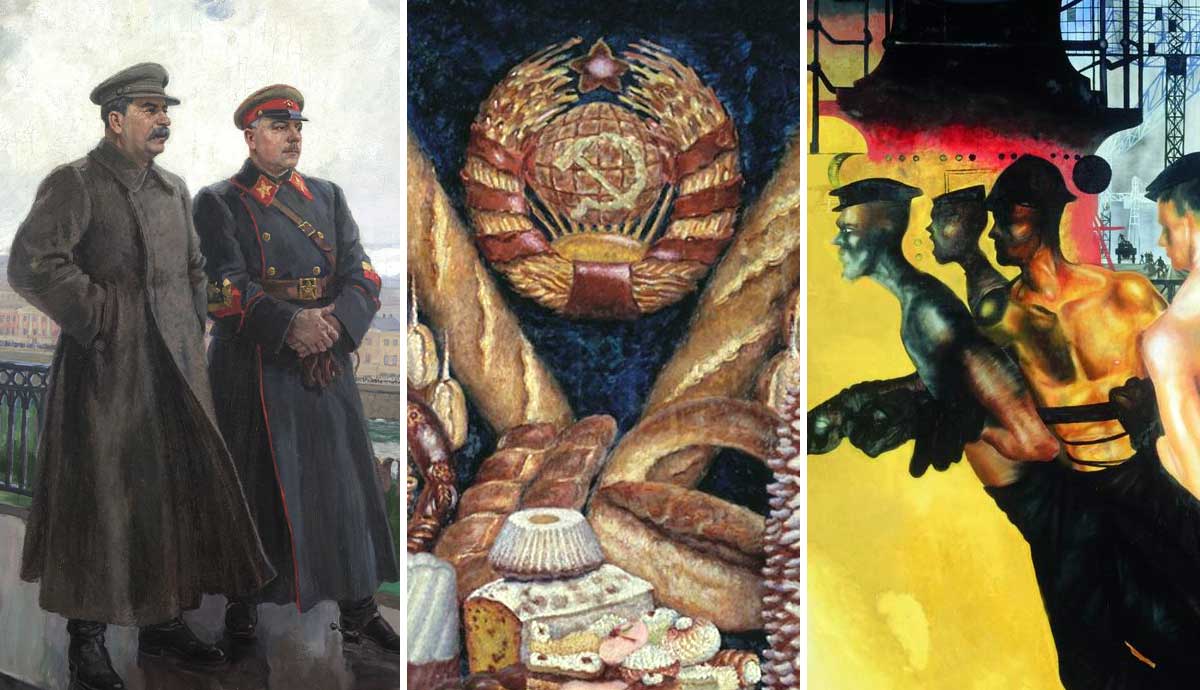

One of the earliest paintings of this style is a work by Yuri Pimenov. The five men depicted are without doubt the subject. They are stoical and unwavering in the face of the blistering flames, even bare-chested as they work. This is a typical idealization of the worker within socialist realism with Stakhanovite-type characters fuelling the engine of society. Due to its early creation in the timeline of art within the Soviet Union, Increase the Productivity of Labour (1927) is unusually avant-garde, unlike the majority of the works that will follow.

The amorphously styled figures approaching the fire and the grey machine in the background with its slightly Cubo-Futurist spirit would soon be removed from Pimenov’s work as we will see an example of in his later piece New Moscow (1937). This is an extremely important piece in the chronology of socialist realism, although undoubtedly propagandist, it is still expressive and experimental. When considering the timeline of this art style we can use it along with later works to exemplify the later restrictions on art in the Soviet Union.

2. Lenin in Smolny, (1930), by Isaak Brodsky

Vladimir Ilych Lenin famously disliked posing for paintings of himself, however, this work by Isaak Brodsky was completed six years after the leader’s death. During this era, Lenin was effectively being canonized in socialist realism artworks, immortalized as the hardworking and humble servant of the proletariat that his public image had become. Brodsky’s specific work was even reproduced in millions of copies and draped through the great Soviet institutions.

The image itself sees Lenin lost in his diligent work, dropped against a humble background without the riches and decadence Russians would have beckoned memories of seeing during the now vehemently detested Tsarist regimes. The vacant chairs around Lenin embed an idea of loneliness, again painting him as the self-effacing servant of the Soviet Union and the people. Isaak Brodsky himself went on to become director of the Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture only two years after completing this work, showing the incentivization for artists to glorify the Soviet Union’s regime and its figureheads. He was also awarded a large apartment on Arts Square in St. Petersburg.

3. Soviet Bread, (1936), by Ilya Mashov

Ilya Mashov was in his early years one of the most significant members of the circle of avant-garde artists known as the Jack of Diamonds. Perhaps most notably, Kazimir Malevich, the artist who made The Black Square (1915), participated in the group’s inception in Moscow in 1910 along with the likes of the father of Russian Futurism David Burliuk and the man Joseph Stalin described after his suicide as the best and the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch, Russian futurist Vladimir Mayakovsky. Of course, many of these members had tentative relationships with the state, as such experimental art was frowned upon, and the group also known as the Knave of Diamonds was disbanded in December 1917, only seven months after the end of the Russian revolution.

Mashov himself, as seen above in Soviet Bread (1936), began following the principles of socialist realism as many other artists within Russia were expected to. Although he did remain true to his love for natural life which can be seen in Still life – Pineapples and Bananas (1938). The hypocrisy in Mashov’s Soviet Breads is palpable, published only four years after the Holodomor in which between 3,500,000 and 5,000,000 Ukrainians starved due to the intentional famine perpetrated by Joseph Stalin within Soviet borders. The contrast between the painting and its bountiful piles of food under a proud Soviet emblem and the historical context is uncomfortable to consider. This piece exemplifies the willing ignorance essential to the propagandist elements of socialist realism.

4. The Stakhanovites, (1937), by Alesksander Alexandrovich Deyneka

Unlike the vast majority of Soviet citizens, Deyneka, as an officially recognized artist, had access to benefits such as trips around the world to exhibit his work. One piece from 1937 is the idyllic The Stakhanovites. The image portrays Russians walking with serene joy when in reality the painting was done at the height of Stalin’s tyrannical purges. As the curator Natalia Sidlina said of the piece: It was the image the Soviet Union was keen to project abroad but the reality was very grim indeed.

The Soviet Union’s international reputation was important, which explains why artists like Aleksander Deyneka were allowed to travel abroad for exhibitions. The tall white building in the backdrop of the painting was all but a plan, unrealized, it features a statue of Lenin proudly standing at the top. The building was to be named the Palace of the Soviets. Deyneka himself was one of the most prominent artists of socialist realism. His Collective Farmer on a Bicycle (1935) was often described as an exemplification of the style so enthusiastically approved by the state in its mission to idealize life under the Soviet Union.

5. New Moscow, (1937), by Yuri Pimenov

Yuri Pimenov, as explained earlier, came from an avant-garde background, but quickly fell into the socialist realist line that the state desired as would be expected and as is clear from the piece New Moscow (1937). Although not entirely naturalistic or traditional in its dreamy and blurred portrayal of the crowds and roads, it is not anywhere near as experimental in its style as the publishing of Increase in the productivity of Labour (1927) ten years earlier. The New Moscow Pimenov is effectively trying to portray is an industrialized one. Cars lined down the road of a busy subway and the towering buildings ahead. Even an open-topped car being the main subject would have been an extreme rarity, a borderline unimaginable luxury for the vast majority of the Russian population.

However, the darkest element of irony comes in the fact that the Moscow Trials had taken place within the city only one year prior to the painting’s publishing. During the Moscow Trials government members and officials were tried and executed throughout the capital, beckoning forth what is commonly known as Stalin’s Great Terror in which between an estimated 700,000 and 1,200,000 people were labeled political enemies and either executed by the secret police or exiled to the GULAG.

The victimized included Kulaks (wealthy enough peasants to own their own land), ethnic minorities (particularly Muslims in Xinjiang and Buddhist lamas in the Mongolian People’s Republic), religious and political activists, Red army leaders, and Trotskyists (party members accused of retaining loyalty to former Soviet figurehead and personal rival of Joseph Stalin’s, Leon Trotsky). It is sensible to conclude that the luxurious modernized New Moscow that Yuri Pimenov is attempting to portray above betrays the violent and tyrannical new order that was enveloping Moscow in these years under Joseph Stalin and his secret police.

6. Stalin and Voroshilov in the Kremlin, (1938), Aleksandr Gerasimov’s Socialist Realism

Aleksandr Gerasimov was a perfect example of the artist the state desired within the Soviet Union at this time. Never going through an experimental phase, and therefore not coming under the heightened suspicion that more experimental artists like Malaykovsky so often struggled to handle, Gerasimov was the perfect Soviet artist. Before the Russian revolution, he championed realistic naturalist works over the then-popular avant-garde movement within Russia. Often regarded as a pawn for the government, Gerasimov was a specialist in admiring portraits of Soviet leaders.

This loyalty and strict retention of traditional techniques saw him rise to head of the USSR’s Union of Artists and the Soviet Academy of Arts. Once again there is the clear incentivization of socialist realism being enforced by the state as we can see similarly in Brodsky’s rise in titles or Deyneka’s granted international liberties. The image itself has a similar heavy and thoughtful gravitas to Lenin in Brodsky (1930), Stalin and Voroshilov are looking onwards, presumably to the audience discussing lofty political matters, all in service of the state. There is no grand decadence in the scene.

The piece itself has only flashes of color. The strong red of Voroshilov’s military uniform matches the red star atop the Kremlin. The clearing cloudy skies with spots of bright clear blue appearing above Moscow are used to perhaps represent an optimistic future for the city and therefore the state as a whole. Lastly, and predictably, Stalin himself is pensive, pictured as a tall brave man, and a beloved father of his country and its people. The cult of personality that would become essential to Stalin’s leadership is evident in this piece of socialist realism.