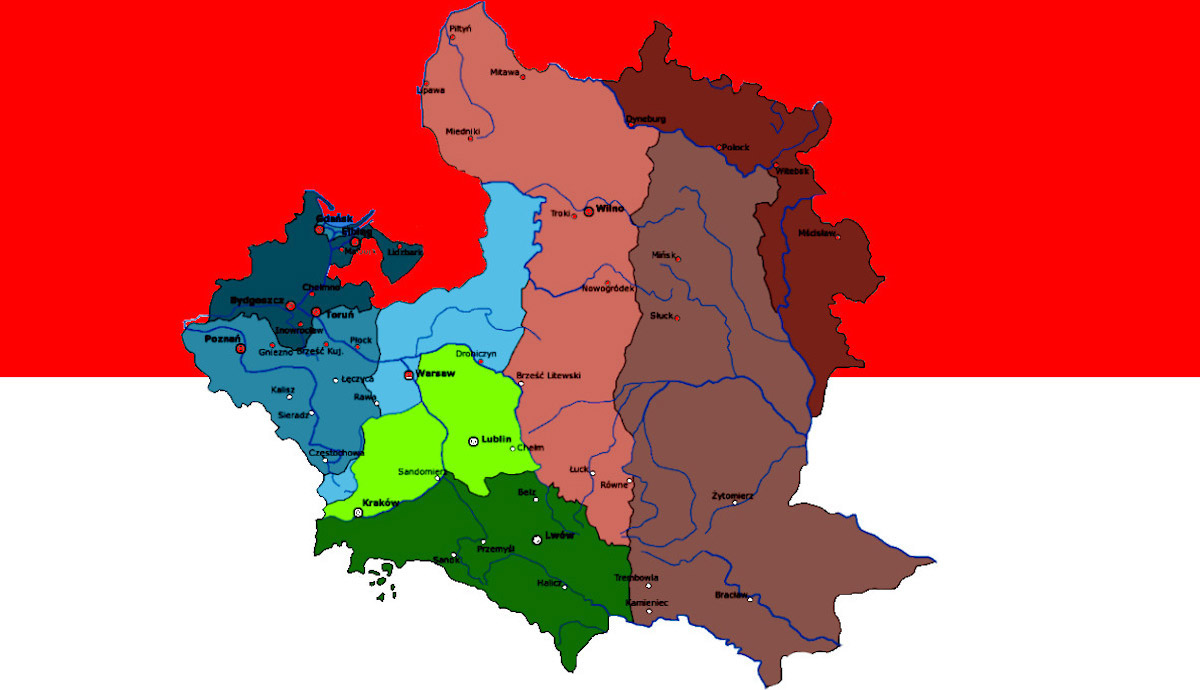

The three partitions of Poland, which took place in 1772, 1793, and 1795 respectively, were devastating for the Polish people. They also marked a turning point in European history in terms of nationalism and imperialism. The partitioning was a result of political, economic, and social factors that had been brewing in Europe for several decades. Prior to the sequence of annexations, Poland was a large and powerful state that had been weakened by conflict within its borders and external pressures from neighboring states. Spotting opportunity, several major geopolitical players in Europe decided to pounce on the advantage – citing the rich trove of resources within Polish borders, as well as its strategic location in the middle of the continent.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a political entity composed of predominantly Polish and Lithuanian Catholics (and many minorities, including a substantial number of Jewish people). The Commonwealth boasted high levels of ethnic diversity as well as religious tolerance among its population of roughly twelve million.

Its monarch was jointly crowned King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, though its languages of administration were exclusively Polish and Latin. The commonwealth was originally established in 1386 via the marriage of Polish Queen Jadwiga to Lithuanian King Jogaila.

In the greater continental scope, the Russian Empire had been rapidly expanding for years under their enlightened Empress Catherine the Great (reigned 1762-1796). This concerned the other European great powers. The Kingdom of Prussia as well as the Hapsburg monarchy – the Hungarian and Austrian branches – were worried over ever-expanding Russia. The Commonwealth, having declined in influence over the decades, was reduced to a quasi-Russian satellite state. These tensions boiled over when Russia clashed with the Bar Confederation – originally backed by France – between 1768 and 1772.

The final king of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski (reigned 1764-1795), was a former lover of Catherine the Great and was installed on the Polish throne with her backing. Despite being an enlightened despot, Catherine was infamous for the lavish gifts and titles with which she showered her nobility and many lovers.

The Partitions of Poland

In 1772, upon the Russian victory against the Polish Bar Confederation, Prussia, Austria, and Russia signed an agreement to divide Poland among themselves. This partition was justified on the grounds that Poland was too weak and unstable to govern itself after the decimation at the hands of the Russians. The three powers would allegedly provide stability and prosperity to the Polish people. This was evidently a thinly veiled excuse for an easy power grab for the three.

Twenty years later, in 1792, Polish and Russian forces clashed again. This time, it was due to the Polish proposal of the Constitution of May 3, 1791 – the second constitution drafted in human history after that of the United States. The constitution, passed democratically, aimed to level the political playing field between commoners and nobility and eliminate the power of veto within the legislative body. The proposition was met with hostility from Russia out of concern and fear of a resurgence of Polish agency – who received backing from Prussia.

The second partition of Poland occurred one year later, in 1793, when Prussia and Russia mutually vied for more Polish territory. This time, there was essentially no justification for the partition, and it was clear that the two powers were simply expanding their own borders at Polish expense. The Russians managed to intimidate or bribe their influence into the Polish legislative body to pass the decision under the veil of democracy. Once a prosperous European superpower, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was now reduced to a fraction of its former self.

The Final Partition of Poland

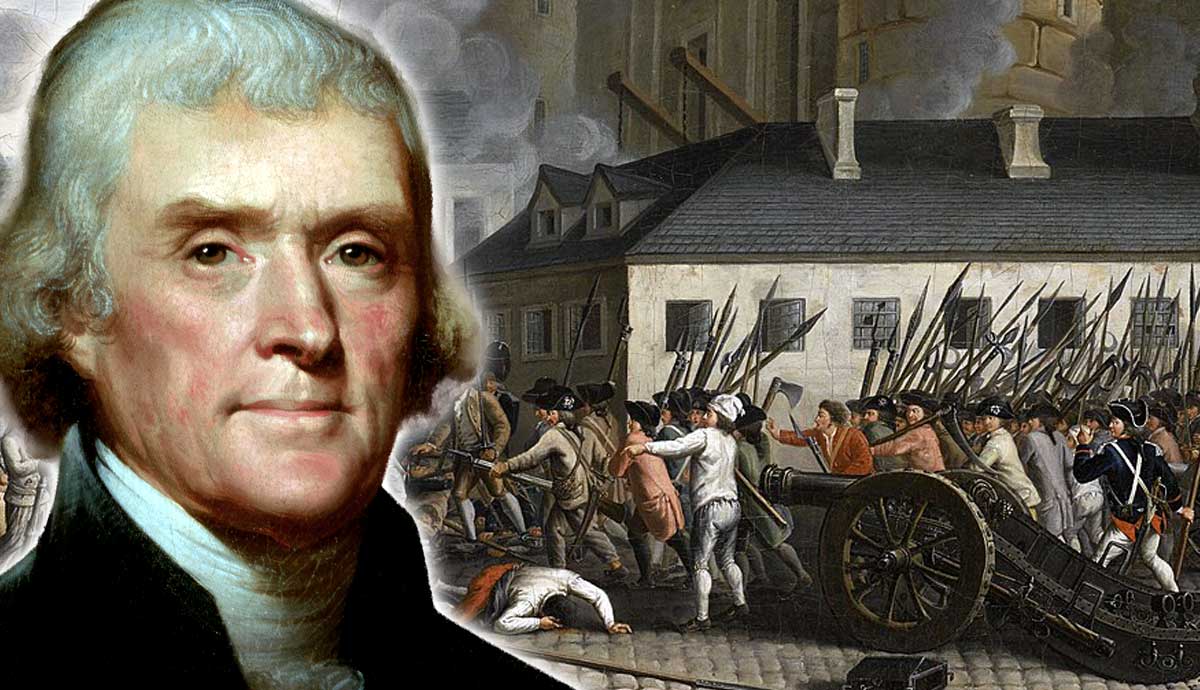

In 1794, a Polish statesman and engineer by the name of Tadeusz Kościuszko – a vehement republican and veteran of the American Revolutionary War – stood up to Polish and Prussian abuse of his country. Kościuszko assembled a ragtag group of revolutionaries and led the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising: a populist movement that paralleled those of the American and French revolutionary movements that had occurred within the same generation.

Despite an early victory led by the military brilliance of Kościuszko, the Polish resistance (which was outnumbered by the superior forces of the Russian Empire three to one) was effectively crushed. Russian troops, crossing through Austria, managed to cut off the Polish supply lines and flank the remaining garrisons. Though he orchestrated a brilliant resistance and won several (non-decisive) victories both offensively and defensively, Kościuszko was eventually captured by the Russians and was brought as a prisoner to Saint Petersburg.

Word of Kościuszko’s successes spread throughout Europe, and he was awarded honorary citizenship of France by the revolutionary French Legislative Assembly.

The third and final partition of Poland occurred in 1795 when Austria, Prussia, and Russia signed an agreement to divide the remaining Polish territory among themselves upon this final blow. This effectively erased the independent Polish state from the map, and the partitioned territories were absorbed into larger European empires. The Polish people were suddenly left stateless and subjected to the laws and policies of their new rulers.

The Aftermath

The aftermath of the Kościuszko Uprising would effectively erase Poland (and Lithuania) from the map for the next 123 years. All the institutions of the previous political entity were banned by the annexing powers and replaced with ones that favored their domestic and dominant cultures.

Due to Prussian forces being tied up in Poland in the aftermath of the bloody final partition, they could not field any support to the French King during the revolution against him. As a result, the Polish state was extremely briefly re-established by Napoleon as a sign of gratitude. The Dutchy of Warsaw (also sometimes referred to as Napoleonic Poland) was reinstated by the Emperor of the French in 1807 but was again occupied by Russian forces in 1815 following Napoleon’s failed invasion of the country.

The nature of the partitions of the country crushed trade. The economic cataclysm, including the collapse of banks, was a result of one market essentially becoming three. The three partitioning powers abused their new territories via taxation and neglected most forms of financing and institutions within their new realms, including education. The Polish and Lithuanian peoples were subject to intense Russification and Germanification.

Russia treated its new territories the harshest. Those who supported the Polish resistance, or backed the insurgences, saw their homes and estates stripped from them by the Russian crown. These assets were subsequently gifted to high-ranking Russian generals or Russian nobility.

The Legacy of the Partitions of Poland

The legacy of the three partitions of Poland is one of tragedy. Poland lost its independence for well over a century. The people were forced to endure tremendous suffering: confiscation of property, forced resettlement, cultural suppression, and forced cultural re-identification. Despite these difficult circumstances, the Polish people never forgot their identity as a nation and continued to stand up for their independence as a people.

The three partitions of Poland were a turning point in European history, as they marked the beginning of a new era of nation-states in terms of political conduct and an end to the fashionable imperial ethnostate. The partitioning of Poland was a clear example of the dangers of imperialism and the importance of political self-determination. The partitions of Poland also had a ripple effect across the European continent, inspiring other nationalist movements and shaping the political landscape of the continent for decades to come.

The historical significance and background of the three partitions of Poland are complex and multifaceted. The partitioning of Poland was a tragic event that left a lasting impact on Polish society and culture. However, it also marked the beginning of a new era in European history and serves as a cautionary (and inspirational) tale about the dangers of imperialism and the importance of self-determination and self-representation in politics. Despite the difficult circumstances faced by the Polish people, they never lost their identity as a nation and continued to stand up for their independence. The legacy of the three partitions of Poland lives on as a reminder of the power of nationalism and the importance of preserving cultural identity.