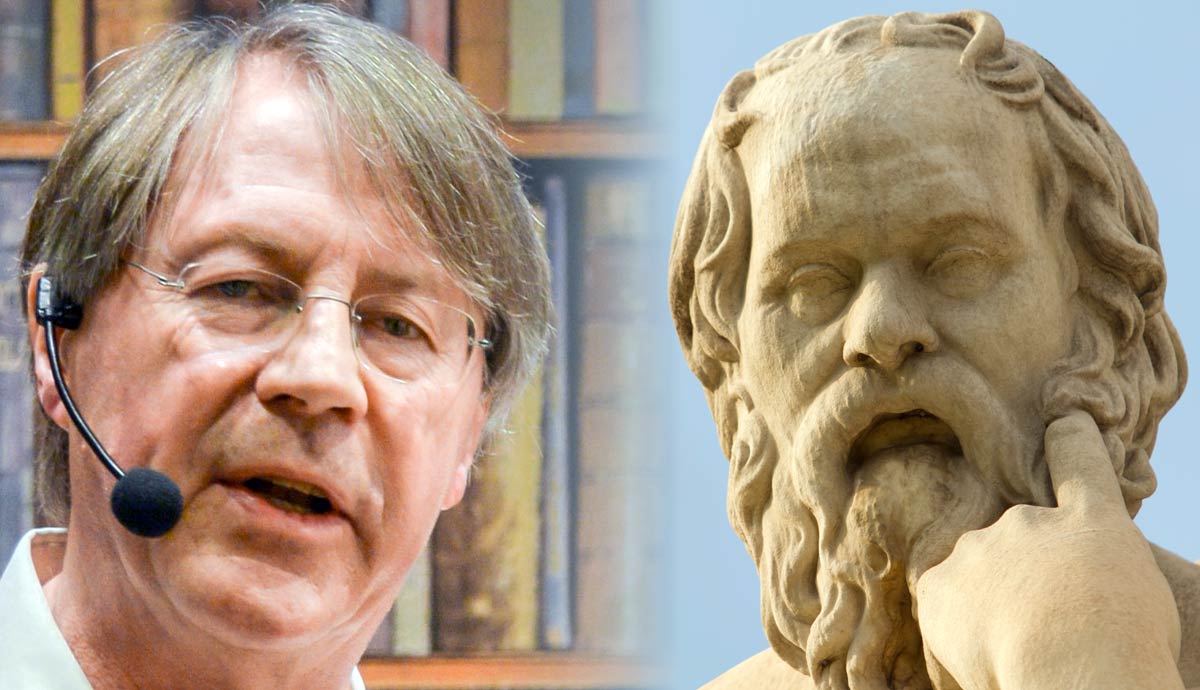

Socrates was a famous Greek philosopher who was often credited as the father of Western philosophy. While many students are familiar with his beliefs around ethics and the unexamined life, fewer are aware of his life story and the social and cultural experiences that shaped the man. In this interview, Richard Marranca talks to Dr. Paul Cartledge, Professor of Greek Culture at the University of Cambridge, about the life and times of Socrates. Get to know the philosopher who changed the world.

Paul Cartledge is Emeritus A. G. Leventis Professor of Greek Culture at the University of Cambridge, and a Global Distinguished Professor at NYU. He was chief historical consultant for the BBC series The Greeks and the Channel 4 series The Spartans — and has been a guest on BBC’s In Our Time and many other programs. Professor Cartledge is also a holder of the Gold Cross of the Order of Honor of Ancient Greece and an Honorary Citizen of Sparta. He has published major books on Ancient Greece, Sparta, Alexander the Great, Democracy, and more.

Dr. Paul Cartledge on Socrates the Man

RM: Can you delve into the life of that matchless, original philosopher, Socrates?

PC: Socrates, son of Sophroniscus, from the political district of Alopeke, was born in 469 BCE. He came of age in 451 BCE and was eligible for Athenian political office from the age of 30 in 439 BCE. He actually held only one known office, selected by lot to be a member of the “Council of 500” in 406 BCE. And, for one day at the age of 63, he was actually selected by lot to be the assembly’s President for a day. That day would be far from normal for Socrates.

The mother of Socrates had been a midwife, and he liked to use midwifery as a metaphor for the intellectual process of extracting truth from dialectical discussion. Or at least, that is how his most famous student, Plato, portrayed him as a character/interlocutor in his Dialogues, though they were all written after Socrates’s death. He died taking a self-administered fatal dose of hemlock after being convicted of impiety by a public jury of his peers in 399 BCE.

Socrates is said to have learned the profession of stonemason, but how he found time to practice it is another matter. He seems to have been kept alive mostly by the subsidies and hospitality of his many rich and often upper-class friends. He is known to have fought twice for Athens against enemy cities in mainland Greece and is said to have displayed exceptional bravery. But that was just two campaigning seasons out of the nearly forty years of his life after turning 30.

Aristotle’s criticism of Socrates’s sons may simply be accurate, though it could also be a trope: famous fathers conspicuously failed to produce equally admirable sons. And Socrates was a notoriously wayward husband. It was even said of him that he had two wives, simultaneously, bigamously, of whom one, Xanthippe, was said to be the proverbial shrew.

RM: Did Socrates retain some of his parental influence in any shape or form?

PC: As well as the midwifery analogy, he was fond of craft analogies involving discussion of technē, Greek for technical skill or expertise. Was there a technē for teaching virtue? That was the main question raised in Plato’s Protagoras dialogue, named for the visiting sophist from Abdera who professed to be agnostic about the gods’ existence and famously declared that man was the measure of things that are and are not. This was an extreme humanist position that was the very reverse of Plato’s “theory of forms.” According to Plato’s theory, there is an absolute sphere of truth and reality beyond human intervention but not beyond (exceptional) human comprehension.

RM: Recently, I was with my wife and child at the Agora in Athens and found myself imagining Socrates on those same stones. (He can also be seen on cups and T-shirts.) What was a normal day for Socrates?

PC: What seems to have been the most “normal” sort of day in the life of this quite extraordinary man and thinker was the day presupposed by the scenario of a Platonic dialogue. According to this, Socrates is found mooching in the center of Athens, often in the Agora area, looking for a suitable conversationalist and conversation topics to engage in dialectics with, asking “Socratic” questions (unanswerable definitively) and using the “Socratic” Q&A method.

Socrates, apparently, was primarily interested in two things: epistemology (theory of knowledge) and moral philosophy (how to live the best life). Plato may actually have coined the word “philosophia.” But in the fictional defense speech, Apology, that Plato wrote for him posthumously, Socrates assumed an activist persona, likening himself to a gadfly seeking to sting the lazy and unquestioning Athenians out of their moral and intellectual torpor and turpitude.

Socrates was not unusual in being a philosopher who walked. Aristotle’s school in central Athens was known as “peripatetic” precisely because the master liked to teach on the hoof. But Socrates, who founded no school, certainly did take his usual method of inquiry and theory, face-to-face questioning, to extremes. Given his other “natural” practices, such as letting his hair and beard grow, it would have been second nature for him to go about sandal-less and barefoot. But not all the scenes of Plato’s dialogues were chance meetings in central Athens. The Republic discussion is set at a rich man’s house in the Piraeus.

Critical Thinking and Socrates’ Fearless Philosophy

RM: Was it arrogant for Socrates to say he knew nothing? Isn’t that like a great football/tennis player saying that they’re amateurs and then overwhelming the competition?

PC: Formally, of course, there is a logical contradiction in asserting the proposition that he “knew” nothing. How did he “know” that? His, and Plato’s, epistemological point was that there is a category distinction to be drawn between “knowledge” and “belief.” No matter how well-founded, empirically, a belief might be, it still remains at one level removed from and, to the strict logician, one level below knowledge properly so-called. On top of that distinction, Plato erected a whole moral-political-philosophical edifice, set out as such in the famous dialogue that we in English refer to as The Republic. Its title in the original Greek was Politeia (polity, constitution) or On Justice (Dikaiosunē).

Socrates, however, never wrote a word of his “philosophy” and may indeed not have recognized his teaching as “philosophy.” Whereas Plato didn’t recognize Socrates’s philosophizing as teaching because he didn’t believe virtue could be taught. For Socrates, dialectic was an argumentative tool, a way of clarifying the minds of his interlocutors and, in particular, ridding them of “ordinary language” beliefs that could not withstand the withering power of a Socratic attack. Thus, when questioned as to what “justice” or “piety” might be, Socrates’s discussants typically resort to assuming that the answer is so obvious that the very concept did not need examination, giving instead instances of what they consider to be “just” or “pious” acts or behaviors. Whereupon Plato’s Socrates tears into them, typically by revealing the fatal logical contradictions that their unexamined assumptions have led them into. The outcome of such a conversation, or rather, verbal contest, not infrequently is “aporia”: a Greek word meaning no (obvious, clear) way forward to an agreed conclusion.

RM: Socrates is coming off like the perennial old man of wisdom, but there’s some competition. Is it possible to say he was like an athlete but of the mind? Do these philosophers, such as Socrates or Plato, enjoy sports?

PC: One can analogize Socrates’s ploy of denying knowledge and then crushing his discussants to that of a super-sportsperson pretending to be only average and then running rings around their fellow soccer or tennis players. Certainly, athletic sports were an issue on Greek thinkers’ agenda well before Socrates’s day. The Olympics were just one of perhaps as many 50 athletics competitions going on around the Greek world by the 5th century BCE.

The Olympics were the oldest, founded in the 8th century BCE, as well as the most famous and prestigious games. Therefore, they raised in the sharpest form the philosophical question: what’s the good of or what’s the virtue in practicing athletics? Philosophers, partly perhaps because almost none of them that we know of was any good at sports, tended to decry and poo-poo the effort that athletes put into making them the best possible runner, wrestler, or whatever because it was a purely physical and not a spiritual virtue that was involved. Socrates was probably of that mind, too.

I said above that “almost none of them” was any good at sports. Plato, however, was very much the exception. Like several of his fellow aristocrats, he engaged in his youth in (nude) wrestling in a gymnasium, a word which means “place of nude exercise.” By repute, he was exceptionally good. So much so that there’s even a suggestion that his name “Plato” was actually a nickname, meaning something like “Broad-y!”

RM: Of the many people I know, perhaps the most truthful is an old friend since grammar school, but he gets unfriended a lot on Facebook. Socrates must have been very courageous and headstrong. But society will often punish such bold thinkers.

PC: Socrates seems to have been fearless in his pursuit of what he considered the truth. Though what exactly he, as opposed to Plato, would have understood by that term is unclear. He does seem always to have sought moral imperatives by which to live a virtuous and examined life. “No one does wrong knowingly or willingly” may have been one of his maxims.

Contrary to the caricature of him presented in Aristophanes’s comic play called Clouds (423 BCE), Socrates did not have his head in the clouds and was a robust, down-to-earth, pragmatic moral philosopher. He was not a quibbler nor a disembodied intellectual. On the matter of the soul, he was ambivalent. Like all Greeks, who didn’t yet situate intellection in the brain, he saw the human soul (psuchē) as the seat of feelings and emotions and of thought. On the other hand, at least if we may believe the Socrates of Plato’s Phaedo dialogue, he did not believe in the immortality of the soul.

Socrates, the Hoplite

RM: Socrates isn’t a poster boy for the military, yet he was known to be courageous, even saving Alcibiades. As a hoplite, didn’t he have some dealings with the dreaded Spartans?

Socrates battled with allies of Athens, Potidaea in north Greece in about 430 BCE, and Thebes in central Greece at Delium in 424 BCE. He did indeed save the life of Alcibiades (c. 450-404 BCE), who was a playboy aristocrat brought up as the ward of Pericles after his father’s death in battle.

In 415/4 BCE, Alcibiades defected to Sparta when placed on trial at Athens for impiety, a crime of which he probably was technically guilty, though the prosecution was brought by personal enemies who disliked his celebrity status and posturing. Rather than return to Athens from south Italy, he gave his minders the slip and made his way to Sparta, where he “went native” and behaved in an utterly Spartan way, even to the extent of sleeping with the wife of an absent king and getting her pregnant. In Sparta, the rules surrounding adultery were much laxer than those in Athens. Unlike his guardian, Pericles, he was very far from a principled democrat. Nevertheless, he wasn’t unhappy to return to Athens, eventually, in 407 BCE, and resume his political career.

His defection to Sparta looks bizarre from the outside but actually was quite calculatingly rational. It didn’t apparently lose him the support of the Athenian masses, nor that of Plato, who gave him a starring role in his Symposium dialogue, which was set in 416 BCE, the year of his spectacular Olympic chariot-racing triumph. He entered seven chariots, one of which took the winning olive wreath prize.

Pericles would probably have been appalled by Alcibiades’s defection, but Socrates, who himself wasn’t the fiercest of democrats, not so much. At least not until he was put on trial for his life in 399 BCE. The main charge against him was impiety, but the second, “corrupting the youth,” was, in effect, a charge of treason. Among the “youth” whom Socrates had allegedly corrupted, one of the most prominent was one-time traitor Alcibiades (dead since 404 BCE).

Religious Beliefs and Impiety

RM: I recall that Socrates intensely pondered for hours. Was he meditating? Was he in touch with his daimon and, if so, what does that mean? Can you tell us about his religious beliefs, including any connection to Eleusis.

PC: He almost certainly would have been initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, as almost all Athenians automatically were. Plato’s Socrates also referred to one particular “daimonion,” or inner voice, of Socrates. This friendly, as Socrates saw it, spirit was a kind of internal mentor that, on occasion, spoke to him and gave him instructions, in every case telling him only what not to do, never what to do. It would have been easy for a hostile prosecutor or jury member to infer either that Socrates was mad or that he was sacrilegiously invoking a divine power to whose support he wasn’t entitled.

There was something mystical about Socrates, and yes, he was said to retreat into a trance-like state, standing up for long periods lost in thought, which could be described as “meditating.” But we don’t know what exactly he was meditating for or about, and it would be quite wrong to connect that with his alleged “daimonion.” A daimonion is a diminutive version, in the neuter gender, of the masculine Greek word daimōn, which is hard to translate. Our word “demon,” which is mainly negative, is a direct transliteration of daimōn and reflects Christian rejection of Greek pagan thought and behavior. Actually, much nearer to our “demons” is daimonia, the plural of daimonion, which is the word used in the main charge against Socrates.

That charge has two parts: a negative and a positive. The negative alleged that Socrates did not duly acknowledge, through religious worship, the gods that the city of the Athenians acknowledged or recognized. The positive charge alleged that he had “introduced” (invented) “other” (i.e. bad), newfangled daimonia. Every word of that charge sheet had a special meaning for the 501 judge-jurors who were trying him. The prosecution’s point was that Socrates was irreligious, not a good Athenian citizen, and, because the Athenians relied on the favor of the gods and goddesses, was endangering what the Romans called “the peace of the gods.”

A majority of jurors were persuaded that Socrates was guilty as charged, but only a small majority. A much bigger majority voted for the death sentence, in preference to a large fine, for example, because they believed that Athens would be better off for his non-existence. Two of Socrates’s famous former pupils, Plato and Xenophon, spoke up posthumously in his defense, but they took different lines. Plato’s was more intellectual. Memorably, Plato’s Socrates asserted that “the unexamined life is not worth living for a human being.” Xenophon simply makes Socrates assert that he was conventionally pious, sacrificing, and so on.

Preference for Spoken Word

RM: Socrates preferred oral culture. If Socrates had the chance to read Plato, Xenophon, and Aristophanes, would Socrates recognize himself?

PC: By the end of Socrates’s life, “books” (papyrus scrolls) were becoming sufficiently well known for there to be a space in the central Agora where they were sold, something that Plato makes his Socrates refer to in his Apology. But they were hardly a commonplace item, and only intellectuals would want to accumulate a private “library” (there was no public library) of scrolls, for example of plays or philosophical treatises or political pamphlets. Even Plato, who wrote beautifully, expressed philosophical reservations about written “wisdom,” but his master Socrates wrote not a word of his teaching and gloried in oral exchange. His philosophical method is known as “elenchtic” from the Greek word elenchos, meaning refutation by cross-examination.

Philosophers Rule

RM: Socrates and Plato have been criticized for preferring an elitist, philosopher-run state. Fear of mobs and demagogues. But Socrates was willing to die fighting the enemies of Athens, the world’s first democracy, and a direct one at that. Can you reconcile these parts?

PC: “Criticized” is putting it a little too mildly. Plato, in the 1930s, came to be seen as a proto-fascist, even a proto-Nazi, figure since he could be read as some kind of “totalitarian.” In The Republic dialogue, Plato uses Socrates to argue that only if philosophers, specifically Platonic philosophers, get to rule the state/city will the troubles that plague actually existent states, mainly civil strife or even civil war, cease. Here, through his character Socrates and his interlocutors, Plato founds an “ideal” state, ideal in two senses. It’s the best possible kind, and it will be ruled on the basis of knowledge of the forms of true reality and good. One of the Greek words translated as “Form” is “idea.” That sketched-out ideal state of The Republic is some kind of epistemonocracy: a power of the eggheads, those in the know. The Laws, Plato’s massive last work, offers a much more detailed working out of what such a state would actually be like in practice: what laws it would make, how it would enforce them, by whom or what it would be governed, and what punishments would be enforced for infringements.

Again, clearly, this “Magnesia” on the island of Crete is to be a narrow oligarchy, but it also contains a huge surprise: atheism, not just a failure to recognize the gods with proper worship but not believing they exist at all, is to be outlawed and punished with automatic death. Ouch. No liberal tolerance for Plato, whose views on male homosexual behavior had also become hardline and very different from the views ascribed earlier to Socrates or presupposed in, for instance, The Symposium. I note that Plato himself was most unusual in never marrying and having a family.

The Beauty Pageant of Philosophy

RM: Why can’t Socrates be the leading symbol for beauty contests? His beautiful soul made him the most beautiful, would that be right?

PC: But what is beauty? In the eye and the mind of the beholder. The most basic Greek word for beautiful, kalos, could also mean morally fine, not just aesthetically pleasing. Plato makes his Socrates refer to himself as bulbous-nosed and bug-eyed and humorously claim that those “ugly” features gave him superior sight and sense of smell. There were beauty contests in ancient Greece, for women as well as for men, but Socrates wouldn’t have stood a chance. The beauty, the truthfulness, honesty, and intellectual capacity of his soul, was another matter.

Aristotle, Socrate’s intellectual grandson, wrote a whole treatise on the soul/mind/spirit (psuchē), usually referred to by its Latin title De Anima. In The Republic, Plato’s Socrates had envisaged the soul as tripartite, made up of intellect, emotion, and appetite, and had used that vision to analogize the nature and governance of an entire city. He believed that the ideal city should be governed by “the fine or beautiful and virtuous,” but that intellectual beauty was more important than physical.

RM: What’s the best way to know about Socrates?

PC: The ‘best’ way to learn about the real, historical Socrates is, of course, a leading question. The two people closest to him who knew him intimately and wrote about him and whose works survive are probably the least reliable witnesses, since they had agendas. Above all, they wished to defend him from the two charges for which he forfeited his life. Speaking objectively, or trying to, I would credit the source that says he was once in his life a member of the Council and for one day in his life selected as President of the Assembly. This was the occasion in 406 BCE when the Assembly illegally, against chairman Socrates’s protests, turned itself into a kangaroo court and condemned six elected generals to death, including Pericles’s son Pericles.

Two years later, Athens experienced defeat, followed by an anti-democratic coup and the imposition of a Sparta-backed junta. Democrats fled the city or fought for freedom in the Piraeus. Socrates did neither. He allowed himself to be enrolled as a citizen in the severely reduced citizen body but defied the junta’s orders in one sensitive matter. The “real” Socrates, as opposed to Plato’s and Xenophon’s versions, was condemned to death in 399 BCE and imprisoned, patiently awaiting the time appointed to drink the hemlock poison. He seems to have faced his death very bravely and to have philosophized to the very end. An intellectual hero and martyr.