At the beginning of the second Achaemenid invasion of Greece the Persians, with an immense army of hundreds of thousands of men, struggled to break through the pass of Thermopylae. Simultaneously, the naval losses during the series of engagements north of Thermopylae also had a negative effect on Persian morale.

Despite the losses, the Persian invasion force was still an overwhelmingly terrifying sight for any Greek to behold. Still, the Persians wanted to make a statement and demoralize the Greeks. The provinces of Boeotia and Attica lay open before them, and at the end of Attica was a worthy target. This is the story of the Persian destruction of Athens.

Before the Destruction: The Second Persian Invasion & the Evacuation of Athens

In April 480 BCE, a massive Persian army of hundreds of thousands of men crossed the Hellespont on two immense pontoon bridges. Their goal was the conquest of Greece.

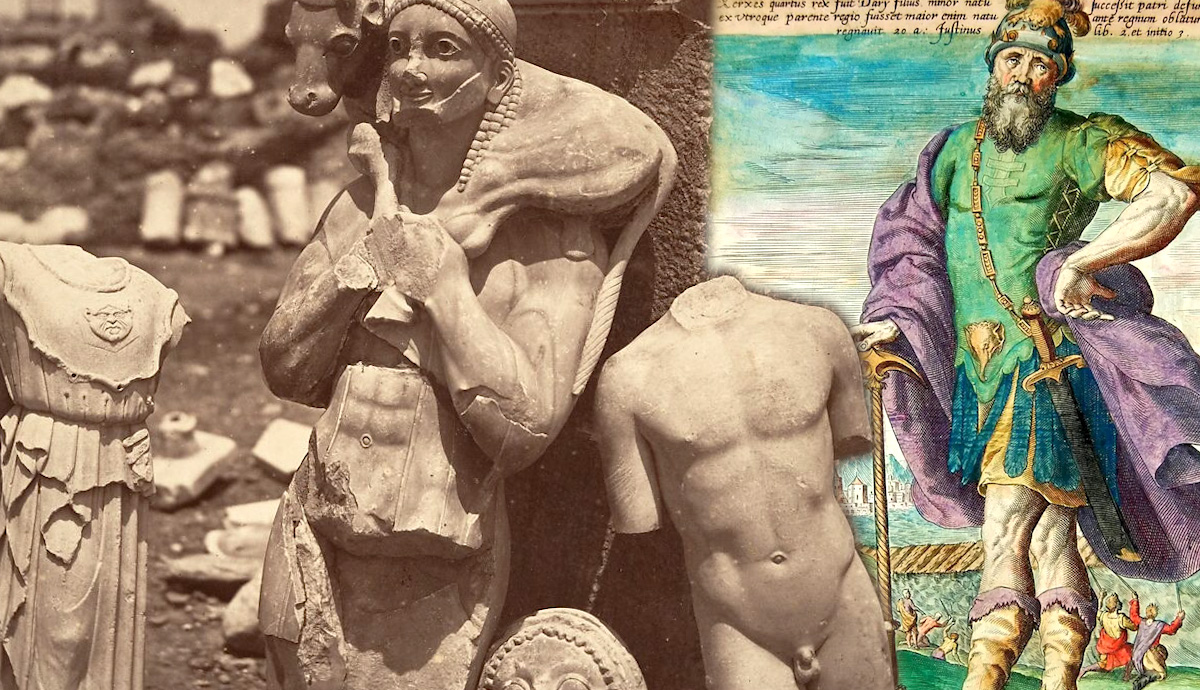

Ten years earlier, they had tried to do so and had failed miserably, being soundly defeated at the Battle of Marathon. This time, the Persian king, Xerxes, made sure he had the numbers to do what his father, King Darius, had failed to do ten years earlier.

The Greeks, however, were not sitting on their laurels. They knew the Persians would come back, and they had been preparing for it. Aided by increased production at the Laurium silver mines, the Athenians had used the revenue to build and outfit a fleet of 200 ships — an act that gave them naval dominance over the other Greek city-states in addition to being able to help counter the immense size of the Persian fleet.

By the time the Persians had crossed into Greece, the evacuation of Athens had already begun. Foreseeing what was to come, the Greeks had consulted the Oracle of Delphi, who advised them to flee the city. Upon a second visit, she told them to rely on their “wooden wall”, which the politician and general, Themistocles, took to mean the fleet.

As early as the winter of 481 BCE, the evacuation had been planned. It would require the relocation of somewhere in the region of 100 000 people, and was a massive undertaking. The majority of the population would be moved to the city of Troezen in the Peloponnese, 50 miles away. Old people and salvageable goods were to be sent to the island of Salamis off the coast of Attica to the west of Athens. Priestesses and treasurers would stay to look after the treasures in the Acropolis. These treasures would be hidden, like the precious goods of the others who would leave. Many things were buried in the hopes that they would be there when the owners returned.

To slow the advance of the Persians and to buy extra time, the Greeks sent a small force to hamper the Persians at the choke point of Thermopylae. There, several thousand Greeks led by King Leonidas and the 300 Spartans held the pass for two days, making use of the narrow defile to reduce the Persian numerical advantage. Simultaneously, a Greek fleet of just under 300 ships harried the enormous Persian fleet in the Straits of Artemisium between Euboea and Thessaly. The naval action protected the northern flank of the Greek forces at Thermopylae. After the Greek forces on land had been defeated, however, the Greek navy pulled back to Athens to complete the evacuation, which the Greek historian Herodotus claims started a few days after the Battle of Artemisium.

After the two engagements, all of Boeotia and Attica laid open to the Persians. Two cities which had resisted the invasion, Thespiae and Plataea, were sacked and razed. Modern historian Robert Garland writes that the scenes in Athens would have been chaotic. Refugees from other areas in Attica would have descended upon Athens in the hope of being evacuated too. The scene at the port would have been one of desperation. People were tired, hungry, and thirsty.

A century after the events, Plutarch imagined the tears as families were parted, and the howls of pet dogs left behind. The city of Troezen, in particular, made great efforts to accommodate the massive influx of people. The Athenian refugees were given a small daily allowance at the expense of the public, while children were allowed to pick fruit from trees in and around the city. Education was also planned for and provided to Athenian children.

Athens Burns

In September 480 BCE, the Persian fleet arrived in Phaleron Bay. A small number of Greeks who barricaded themselves in the Acropolis were quickly defeated, and Xerxes ordered the city to be put to the torch. The Acropolis was destroyed, including the Old Temple of Athena and the Older Parthenon.

Herodotus writes that “Those Persians who had come up first betook themselves to the gates, which they opened, and slew the suppliants; and when they had laid all the Athenians low, they plundered the temple and burnt the whole of the acropolis”.

The Battle of Salamis

Immediately after the Persian sack of Athens, the Greek fleet under the command of Themistocles lured the Persian fleet into the Strait of Salamis. The Greeks understood that if they lost here, then all of Greece would be open to invasion. They made their stand and against superior numbers, inflicted a grievous wound on the Persians, sinking hundreds of ships with a loss of only 40 of their own.

Such was the chaos of the battle that the Greeks weren’t even sure of their victory until the smoke had cleared the following morning, and they saw the Persians in retreat. Xerxes, who had set up his throne on Mount Aigaleo overlooking the strait, was in a foul mood, and several men lost their heads.

After the battle, a trickle of Athenian refugees returned to their city to find their homes burned and the butchered corpses of those who had stayed. The devastation in Athens was a miserable sight to behold.

Mardonius Attacks

Realizing their precarious position, Xerxes led the majority of the Persian fleet back to Ionia. His general, Mardonius, volunteered to stay in Greece and complete the conquest. With him was an army composed of between 70 000 and 120 000 soldiers (by modern estimates). The best troops, such as the Immortals, the Medes, the Sacae, the Bactrians, and the Indians, all stayed.

Meanwhile, the Greeks had hurriedly, but diligently been building a defensive wall across the Isthmus of Corinth which separates northern Greece from the Peloponnese. Mardonius knew that to defeat the Greeks, he would have to draw the Spartans out from behind the wall. The Athenians also knew they couldn’t defeat the Persians without the Spartans.

Mardonius decided to offer peace to the Athenians, along with promises of self-rule and territorial expansion, in a bid to exploit the rift between the Athenians and the Spartans. The Athenians pretended to entertain the offer and made sure the Spartan delegation was present at the talks before turning the offer down.

Enraged, Mardonius returned to his army. Knowing what was to come, the Athenians quickly evacuated their city again. This time, the Persians left very little standing. Athens was completely razed.

The Battle of Plataea

The second Persian sack of Athens left the Spartans with little choice but to honor their alliance with the Athenians. It seemed prudent to try and defeat the Persians before the Persians came south to the Spartan homeland. So they marched north and joined up with Athenians and the other Greek allies. What followed was the Battle of Plataea, and despite making severe tactical errors, the Greek hoplites proved far too much for the Persians. The Battle of Plataea crushed the Persian forces, killing Mardonius in the process, and ended the invasion for good.

Rebuilding of Athens

In the Autumn of 479 BCE, the Athenians immediately began rebuilding their devastated city. With Themistocles in charge of reconstruction efforts, priority went to the defensive structures, especially the Themistoclean Wall, to prevent future invasions. Although the Persians were defeated, Athens still had a potential enemy in the Spartans.

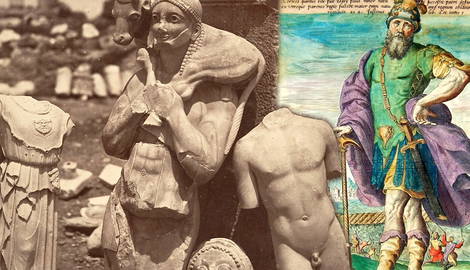

Rubble was used to reconstruct houses and temples, while the Parthenon had to wait thirty years to be rebuilt.

Persian Destruction of Athens: Conclusion

The Persian sack of Athens (twice) was a major blow to the Greeks, yet it served to unite them against the army of Mardonius. It was a low point of the war, yet it was also the catalyst for the Greeks to completely destroy the invaders.

A century and a half later, the conquests of Alexander the Great would visit retribution on the Persians. According to Plutarch and Diodorus, the Palace of Persepolis was razed as an act of revenge for the destruction of the Temple of Athena.