The New Testament mentions four people with the name Philip. Two were sons of King Herod the Great, and one Philip features in Acts. Scholars generally refer to the latter as Philip the Evangelist or Philip the Deacon. The subject of this article is Philip the Apostle, one of the Twelve Disciples of Jesus. Though he plays a much smaller role in the New Testament narrative than Peter, John, James, and Andrew, he nonetheless made a significant contribution when he spoke up.

First Encounter and Calling as a Disciple

The synoptic gospels do not detail the call of Philip as a disciple of Jesus. John tells us that Philip resided in Bethsaida, the town by the Sea of Galilee where Peter and Andrew were from. Jesus’s decision to travel to Bethsaida seems to have been intentional: to call Philip and, via his evangelistic endeavor, to meet Nathanael. There is no context to the calling of Philip other than the words “Follow me.”

Character and Personality

The synoptic gospels do not provide more information about Philip other than naming him in the lists of the disciples. John, however, provides the bulk of what we know about him. From the information available on Philip, which is not much, we can build a profile of this disciple.

Philip strikes the reader as a doer. When Jesus called him, Philip found Nathanael and told him they “have found him of whom Moses in the Law and also the prophets wrote, Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph.” He used the plural, they, indicating Philip was with someone else when he made the discovery. Comparing his words with those of Andrew sharing his discovery of the Messiah with Peter, there is a remarkable correlation. Some scholars have speculated that Philip was the second apostle who joined Andrew in visiting with Jesus. If true, Philip also followed John the Baptist before following Jesus.

The way Philip conveys that he found Jesus indicates that he may have been a devout Jew, familiar with the Hebrew Old Testament or Tanak. He also shares where Jesus was from and that he was from Joseph’s household, which suggests that he explained to Nathanael how Jesus fulfilled the prophecies and why he is the promised One.

Philip’s act of calling another person to come to Jesus and that person becoming a disciple also reminds us of Andrew. The two seem to have had similar personalities, and both were seekers of deeper insight and tended to bring people to Christ.

Philip is a Greek name that may point to Philip’s openness and exposure to other cultures. Later, Greek men from Bethsaida, where Philip was from, approached Philip and asked to meet Jesus. They may have recognized or known Philip and known that he could speak Greek, motivating them to approach him rather than one of the other disciples. Philip went to Andrew, sharing their request, and the two facilitated the meeting with Jesus. His later ministry in Greece, Phrygia, and Syria may also indicate his linguistic ability and affinity for other cultures.

Significant Encounters

John 6:5-7

“Lifting up his eyes, then, and seeing that a large crowd was coming toward him, Jesus said to Philip, ‘Where are we to buy bread, so that these people may eat?’ He said this to test him, for he himself knew what he would do. Philip answered him, ‘Two hundred denarii worth of bread would not be enough for each of them to get a little.’”

The synoptic gospels include the narrative of the miracle Jesus performed by feeding the 5,000. Only John, however, records the conversation between Jesus and Philip. Jesus may have asked Philip this question to test him, but it could also simply have been a method to bring home to him how significant the miracle would be that he was about to witness.

Philip looked at the situation they faced from a practical perspective, noting that it was impossible to resolve the problem even if they had access to a significant amount of money, which they did not have. Though he must have seen Jesus perform miracles before, perhaps he did not consider this dilemma significant enough to justify a miracle.

John 14:8-11

“Philip said to him, ‘Lord, show us the Father, and it is enough for us.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Have I been with you so long, and you still do not know me, Philip? Whoever has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, “Show us the Father?” Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in me? The words that I say to you I do not speak on my own authority, but the Father who dwells in me does his works. Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father is in me, or else believe on account of the works themselves.’”

Philip’s question after the Last Supper shows his keen desire for more insight. It created the opportunity for a significant discourse on the unity between Jesus and his Father. In his response, Jesus affirms his divinity and how Father and Son are distinct, yet one, a principle that underlies the concept of the Trinity.

In his response, Jesus also calls on his disciples to believe, promising they would perform greater things than those he had done. He foretold how the Holy Spirit would teach and empower them. The missionary endeavors spread the gospel much farther than Jesus’s ministry did, though it was by and through him that they could reach the world.

Legacy and Tradition

According to Clement of Alexandria, a late 2nd-early 3rd-century Church Father, Philip is the unnamed disciple who wanted to bury his father before continuing to follow Jesus. This story is part of a section that deals with the cost of following Jesus and the gospels recorded it in Matthew 8:18-22 and Luke 9:57-62.

The Nag Hammadi library contains a document titled Letter from Peter to Philip. In it, Peter calls on Philip to return from his sole missionary journey and join the other apostles on the Mount of Olives. Philip seemed reluctant to return from his mission for an unknown reason. The reliability of the account recorded in this gnostic text is doubtful.

Legend holds that Philip ministered in Scythia in central Eurasia, further south in Phrygia (an area in modern-day Turkey), and Syria. The reliability of this account is doubtful since the source, the Acts of Philip intermingles fact with fiction. The document includes an account of a dragon, among other dubious content.

That said, Eusebius of Caesarea, a 4th-century Church Father, attests to Philip’s ministry in connection with Hierapolis and mentions that he died a martyr. He does not provide any detail on how Philip died. Other accounts claim that Mariamne, Philip’s sister, ministered alongside him and was also martyred.

Though traditions differ on his death and exactly where he ministered, what they have in common is that Philip made a significant contribution to the Christian faith through his evangelism.

Death

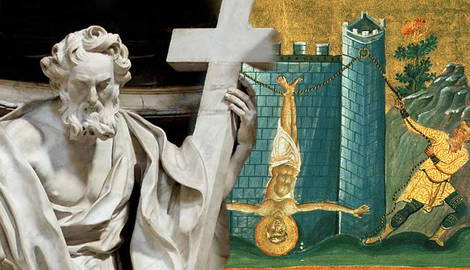

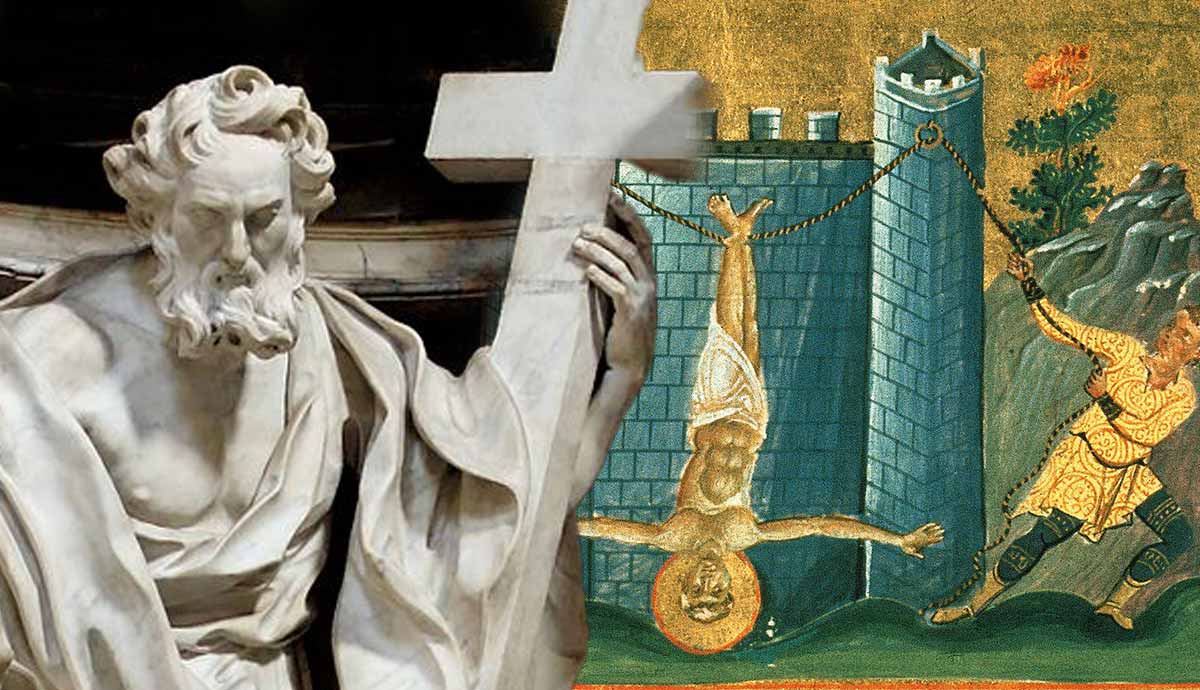

Exactly how Philip died is not clear. Some traditions hold that Philip was stoned to death, while others suggest he was crucified upside down. These accounts may not be mutually exclusive as it is possible that Philip died from the wounds he sustained when being stoned while being crucified. Several accounts of martyrdom mention stoning before crucifixion as part of the torture process when executing people.

Some of the earliest traditions have Philip martyred in Hierapolis. According to the apocryphal Acts of Philip, the wife of the proconsul converted, which angered the Proconsul who promptly had Philip and Bartholomew crucified upside down. While hanging there, Philip preached to the crowd of onlookers who were so moved by his words that they wanted to release them. Philip then had them remove Bartholomew but chose to remain on his cross. The account of Philips’s death from being crucified upside down seems to be supported by Eusebius of Caesarea and Clement of Alexandria.

The 2011 discovery of the tomb of Philips of Hierapolis supports the theory that he was martyred in that city. Archeologists found the tomb among the ruins of a church found at the ancient excavation site of Denizli in western Turkey. Philip died around 80 CE.