American history textbooks relegate the Philippine-American War to the afterthought effects of the more significant Spanish-American War. Even then, in an average school textbook, the latter takes up only half the length of the chapter on the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. But did you know that despite being separated by decades and differing geopolitical contexts, the Philippine-American War and the Vietnam War share striking similarities in their origins, conduct, and legacies?

American Imperialism

Having watched the major European powers spread their empires worldwide, particularly in Africa and Asia, the United States was ready for its imperialist chapter. The decades following the American Civil War, marked by the continued social unrest of Southern Reconstruction, gave way to new feelings of cultural superiority and desires for new overseas markets.

Turner’s Thesis, or “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” formulated by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893, famously declared the frontier, a transformative and dynamic force in shaping American identity, closed according to the 1890 census. Turner contended that the nation’s ability to expand promoted the very rugged individualism, entrepreneurship, and self-reliance that led to the nation’s significant economic, political, social, and even military growth.

With western expansion, which had begun with the very acquisition of British lands past the Appalachian mountains during the American Revolutionary War, American thinkers, politicians, and military leaders now called for the United States to continue its path of greatness past its natural borders.

By 1890, the interests of industrialists hoping for new international markets for their products and proponents of Anglo-Saxon superiority converged to help elect a pro-expansionist governor of Ohio, William McKinley, in 1896. By then, popular speeches and publications had awakened the American population’s desire for a great overseas empire.

Famous at the time, American writer and clergyman Josiah Strong urged the government to acknowledge its fate as a nation destined to spread its greatness worldwide. “This powerful race will move down upon Mexico, down upon Central and South America, out upon the islands of the sea…” Strong wrote in his best-selling work Our Country.

Admiral Alfred T. Mahan of the Naval War College seconded the notion in his top-rated 1890 book, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History. The argument called for the creation of a large and powerful navy, supported by the acquisition of overseas military bases, to help grow and protect American industry and its merchant marine. All the United States needed now was a cause and a grand purpose to spread its imperialist wings – one handed to them on a silver platter by the long-standing Monroe Doctrine and overextension of Spanish power in Cuba.

The Spanish-American War

It would not be too far off from the truth to say that the United States used the pretext of Cuba and the subsequent Spanish-American War as a pretext to steal Spain’s empire and set itself up as a proper imperialist nation in charge of overseas colonies. Cuba had been struggling for independence from Spanish rule for years. The 1823 Monroe Doctrine called for stopping any further European interference in Latin America and insinuated American support of any nation fighting for its independence from the Old World powers.

By the 1890s, sensationalist newspapers, particularly those owned by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, exaggerated Spanish atrocities in Cuba to sell newspapers and influence public opinion, already swayed toward the Cuban cause. Amid the growing public pressure and supported by influential politicians eager for new markets, President McKinley used the mysterious explosion of the USS Maine, an American battleship stationed in Havana, to declare war on Spain on April 25, 1898.

The war primarily took place in two main theaters: the Caribbean and the Pacific. The most famous battle was the naval contest, the Battle of Manila Bay, where the US Navy, led by Commodore George Dewey, destroyed the Spanish Pacific fleet in the Philippines.

“The Splendid Little War,” as it came to be known, lasted only a few months, concluding with a sweeping American victory and Spain recognizing Cuba’s independence and ceding Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. The United States was now a colonial power with interests extending beyond its own shores. However, the American people quickly learned that controlling their newly acquired empire would be far from easy.

The Origins of the Philippine Insurrection

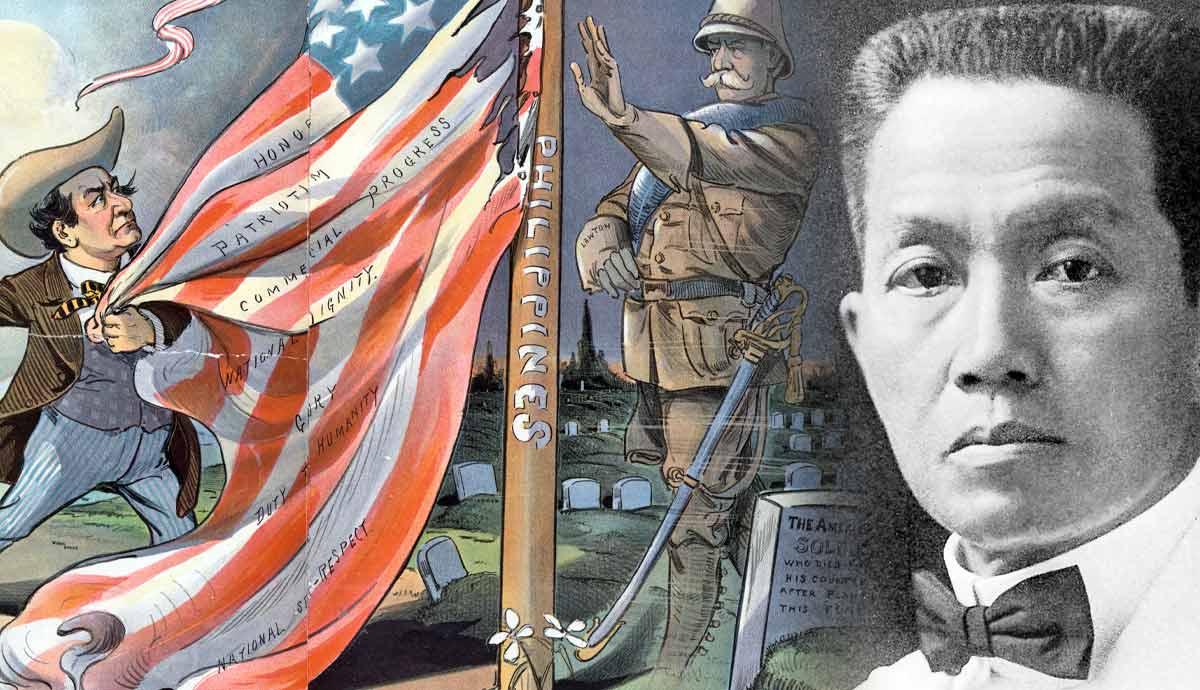

While each of the acquired regions had its own share of difficulties, none would prove to be as challenging as the Filipino independence movement spurred on by its leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, who called the United States’ decision to remain in his country after helping his people defeat Spanish rule, “a violent and aggressive seizure.”

The Philippine-American War, or the Philippine Insurrection, would last more than three years and see nearly 126,000 American soldiers sent to the nation’s jungles to fight against a nationalist movement characterized by guerrilla warfare.

The Filipino aspirations for independence were deeply rooted in its decades-long struggle against Spanish colonial rule. Emilio Aguinaldo, a prominent Filipino revolutionary leader, emerged as the key leader in his people’s movement for independence. When the revolution broke out in 1896, Aguinaldo, a son of landowning nationalists, was already an influential figure in his native province of Cavite and was involved in underground nationalist activities as part of the secret society known as Katipunan whose sole goal was Filipino independence.

In August 1886, Spanish authorities discovered the Katipunan, triggering mass arrests. Aguinaldo and other leaders decided the time was right to take up arms against the Spanish. The revolution quickly spread as rebel forces used guerrilla tactics to launch attacks on Spanish garrisons, government offices, and critical infrastructures.

Seeking to weaken the Spanish Empire during its own conflict with the European power in 1898, the United States recognized the benefits of supporting the Filipino nationalists. In exchange for Aguinaldo’s support in the Philippines through providing intelligence and assisting in the blockade of Manila, the American government promised independence to the Filipino leader.

The American forces even allowed Filipino troops to enter Manila first after the famous American victory, creating the impression that Aguinaldo’s troops had liberated the city themselves. That is not to say that they would not have done it themselves, having successfully held their own against the Spanish forces—still, the Filipinos were never quite able to secure a complete victory, not until the US entrance, that is.

On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo proclaimed the Philippines’ independence from Spanish rule and established the First Philippine Republic with himself as its president. Yet, things quickly unraveled when the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Spanish-American War, transferred the Philippines’ sovereignty from Spain to the United States.

The Philippine-American War Begins

Attempts to negotiate the terms of Philippine sovereignty between United States representatives and Filipino leaders proved futile. The decision about what to do with the Philippines had divided the American public at home. Still, a handful of influential policy makers like Senator Henry Cabot Lodge convinced enough members of Congress to see the Philippines as a valuable strategic and economic asset that should be incorporated into the American empire.

Despite the initial cooperation during the Spanish-American War, the continued presence of United States troops in the Philippines and the lack of clear American policy about the new nation’s sovereignty led to the collapse of negotiations.

The exact trigger for the skirmish near Manila on February 4, 1899, remains unclear, but some accounts suggest that a misunderstanding or miscommunication between American and Filipino troops may have sparked it. Regardless, Aguinaldo now ordered his troops to attack American soldiers.

With the American population and Congress at home divided between fully annexing the Philippines or granting it its sought-after independence, failing to reach a consensus, the United States decided to commit troops to a conflict in a faraway Pacific land most Americans in 1899 could not identify on a map.

More than 4,300 Americans and an estimated 50,000–100,000 Filipinos would die throughout the unpopular war in which the American forces would adopt many of the same questionable policies their government had condemned Spain for using against its colonies, such as torture and the killing of innocent people. In retrospect, the American people could not have known it, but the conflict would prove to a significant extent to be a facsimile of another unpopular conflict sixty years later: the Vietnam War.

American historian Robert Leckie was not wrong in his The Wars of America, initially published in 1961, when the World War II veteran of the jungles of the Pacific War surmised that the Americans should have but failed to learn what it would mean to fight the Filipinos from the Spanish. There would be no easy victories in this war that saw a colonial power fight against local nationalist movements in the deep and sweltering Asian jungles.

Had the Americans asked the defeated European power who had fought Aguinaldo’s forces for years, Leckie wrote, “the Spaniards might have said, ‘You will not stamp out the insurrection so soon; you will have no great and decisive blaze of battle, but hundreds of small brush fires flaming up all over the islands.’”

Major General Ewell Otis commanded the US forces in Manila. He was known for being brilliant but arrogant, both dangerous qualities fueled by Admiral Dewey’s navy and 21,000 soldiers to back up his aspirations of breaking the Filipinos’ will to resist.

Divided into two divisions under Thomas Anderson and the later-famous Arthur MacArthur, the American forces faced Aguinaldo’s army of 80,000 Filipinos—a third of whom had no rifles or guns to speak of. The local military force was shocked that the Americans threw all their firepower, including artillery, machine guns, and .45 caliber Springfield rifles, at them during the day instead of waiting for the evening.

The former conflict against the Spaniards always saw both sides attacking at night and then retreating during the day to rest and escape the jungle heat. The Americans were different. The Naval artillery barrage supporting the American troops was especially jarring for the Filipinos, who soon took to the hills with the US forces in pursuit.

A War of Attrition

The first battle’s American losses of 59 men and 278 wounded paled compared to the Filipino casualties. Allan R. Millett’s For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States estimated the independence fighters’ losses three times those of the invading world power. Aguinaldo’s army would never make the mistake of facing the Americans in an open battle of mass assaults. Therefore, both sides settled for a small guerrilla war for the remainder of the three-year-long conflict.

The Filipinos would randomly emerge and give battle only to disappear into the jungles and mountains as quickly as they appeared, leaving behind American casualties. Anderson and MacArthur’s forces spent days sending out small patrols and searching for the enemy, frequently failing to distinguish between soldier and civilian as the Filipino freedom fighters did not wear any uniforms.

President McKinley’s initial orders for the Filipinos to recognize US authority were blunt when he granted the Military Governor of the Philippines and Otis’ superior, Major General Wesley Merritt, permission to “use whatever means in your judgment are necessary to that end.”

The war soon became one of attrition as US troops entered apparent friendly villages only to have enemy insurgents come out of nowhere and fire upon them. Other times, Leckie wrote, “the doughboys entered villages where their comrades had been held captive, only to find tortured bodies boloed to pieces.” Adding, “the reply was to burn the village and slaughter its men, women, and children.”

Both sides fought the unorthodox with equal terror, with Aguinaldo’s guerrilla forces raiding American camps, stealing supplies, and slaughtering US troops in isolated outposts.

Soon, the torture and destruction of Filipino property by frustrated military forces reached an apex when President McKinley called upon future American President William Howard Taft to assume the first civilian governorship of the islands in late 1900. Otis was relieved of his military duties and replaced by Arthur MacArthur when news reached American newspapers of a new “water torture” developed by American interrogators. Captured Filipinos unwilling to divulge information would have five gallons of water poured down their throat to simulate drowning. Often, when the prisoner expired, they would be revived only to have the torture continue. Now, the United States took on the role of the savior of the Philippines, albeit one that the nation’s people did not want.

Winding Down the War

MacArthur continued to seek out the enemy, whose casualties began to mount to tens of thousands. The US forces did not fare much better, with Americans dying from both battle wounds and disease. In one instance, Millett writes, an American unit of 4,800 had 2,160 men out of commission and in hospital due to the heat, bad food, disease, and exhaustion.

And then it started to rain. Between May and October 1900, over 70 inches of rain had fallen on the tired American men dreaming of returning home while resenting the war more each day. As the armed forces continued their battle against the insurrectionists, Taft showcased the United States as a benevolent power sent to help their Filipino brothers and sisters.

Beginning with Manila and then extending outward, the United States spent millions of dollars instituting reforms and building up the islands’ transportation, education, and public schools in their bid to convince the Filipinos that they were there to end the death and destruction.

Soon, “new railroads, bridges, highways, telegraph, and telephone lines strengthened the economy and forged a new interdependence among the islands,” Millett wrote decades later. “The Army created a school system, which reduced illiteracy, and the military public-health assault on disease virtually eliminated smallpox and plague and reduced the infant mortality rate.”

By 1901, the new reforms slowly began reducing Filipino hostility, with the US Army now having an increased number of Filipino collaborators willing to give up information on Aguinaldo’s hiding places—something unimaginable in the first year of the war. While appearing to subside, the conflict now took on another dimension as it turned brother against brother.

Those who took positions within American-sponsored programs and institutions were labeled as traitors and targeted by the insurrectionists. Although the US forces felt more secure in controlling the Philippine Islands, the guerrillas still held their own—at least until Spring 1901. In March, the American troops, guided by Filipino scouts, staged a raid on Agunaldo’s secret compound and finally captured the elusive leader. After surprisingly little coercion, the Filipino leader arrived in Manila on March 28, ready to surrender. Treated with respect and afforded certain privileges, on April 19, 1901, Aguinaldo issued a proclamation accepting American sovereignty and calling on his followers to do the same.

Initially, the insurrection continued, especially in the southern islands, but equally ferocious American reprisals countered any massacres at the hands of the rebels. The general feeling was shifting, and the Filipinos’ will was wavering in light of American violence and concurrent civic benevolence. Now mostly leaderless, thousands of guerrillas began surrendering daily.

Capitalizing on the insurgency’s all but imminent collapse, President McKinley transferred all executive power from the military to the American civil government in the Philippines on July 1, 1901. The US-appointed governor now shared legislative power with a legislative body comprised chiefly of Filipinos. By the end of the summer, the new Filipino government created the Philippine Constabulary. Modeled after the United States Army and organized along military lines, the Constabulary consisted of 3,000 Filipino recruits and was supervised by American officers.

Another Vietnam?

Small pockets of resistance continued but were gradually suppressed by the withdrawing American forces and the Philippine Constabulary. By 1902, the latter had nearly doubled in size as it began taking on more considerable responsibility for maintaining order in the Philippines as the American forces departed.

On July 4, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt, who took over after President McKinley was assassinated on September 6, 1901, proclaimed a successful end to the war. While some of the war’s atrocities made their way back home via the returning troops, Congress managed to suppress any public outcry—it would have been hard in the face of victory.

Historian Allan R. Millett perhaps summarized the feeling best when he wrote, “An era of romantic nationalism made sustained criticism of the nation’s ‘duty’ to spread civilization difficult, and most Americans had trouble remaining morally indignant about events 7,000 miles away involving a nonwhite race.”

The comparisons between the Philippine-American War and its 20th-century counterpart, the Vietnam War, are striking. Both conflicts took place in Asia and within the context of colonialism. On a superficial level, the Philippines was a colony of Spain before the Spanish-American War, after which it became a colony of the United States. Conversely, Vietnam was a French colony before the First Indochina War. In both cases, local nationalist movements sought independence from their colonial rulers and, later, the United States forces. Both conflicts involved significant guerilla warfare tactics by the regional forces against the better-equipped Americans and the latter’s counterinsurgency measures aimed at winning over the local population. And lastly, both led to inhumane atrocities on either side of the conflict.

In the end, like its distant counterpart, the Philippine-American War, despite being relatively brief, had enduring effects on the local population and politics. While the Filipinos eventually gained independence from the United States in 1946, the conflict left deep scars on the nation.

The war resulted in significant loss of life and destruction, with estimates of Filipino casualties in hundreds of thousands. Like the Vietnam War, the brutality of the conflict, marked by atrocities committed by both American and Filipino forces, left a legacy of trauma and resentment among the Filipino people.

The experience of resistance against American colonialism and the struggle for independence became central to the Filipino people’s national identity and collective memory, shaping their attitudes toward foreign intervention and nationalism in the years to come. Now, if only the American people could remember the conflict past the mere paragraph hastily added at the end of the chapter on the Spanish-American War in their school textbooks.