Time is something we deal with every day. We usually characterize as split between past, present, and future. The progression of time is embodied in our experience—the future becomes the present, and the present becomes the past. In fact, it is impossible to talk about movement and dynamics without the concept of time and its progression. Though our perception of time is similar to our perception of space, time is a far more philosophically demanding topic.

The Nature of Time

What is time? This phenomenon can seem mysterious. Indeed, time, on the one hand, is omnipresent and in some sense omnipotent (contrary to the well-known Arab saying, “Everything in the world fears time, yet time fears the pyramids,” there will likely be an end to the pyramids as well).

On the other hand, although we all intuitively understand what it is, it seems almost impossible to give a precise and comprehensive definition of the concept of time.

One way of thinking of time as “a universal form of change.” “Universal” in this formulation means all-encompassing because any changes are really possible only within time.

“Form” in the definition means that time resembles a kind of transparent vessel that can be filled with any content. In other words, the changes can be very diverse, but the passage of time in which they occur seems invariably uniform and inexorable.

Finally, taking a look at the concept of “change,” we come to the flip side of the coin. It seems that while change is inconceivable without time, time is also inconceivable without change. Indeed, the imaginary stoppage of time is associated with the complete freezing of life and the universe.

So, time is the world’s common denominator; one might say—the main currency of reality. We experience it in different ways: sometimes, we consider the past as something lost and regret it; we try to use the present wisely so that our future will be better; and at times, we eagerly await what is coming next.

The First Mentions of Time in Philosophy

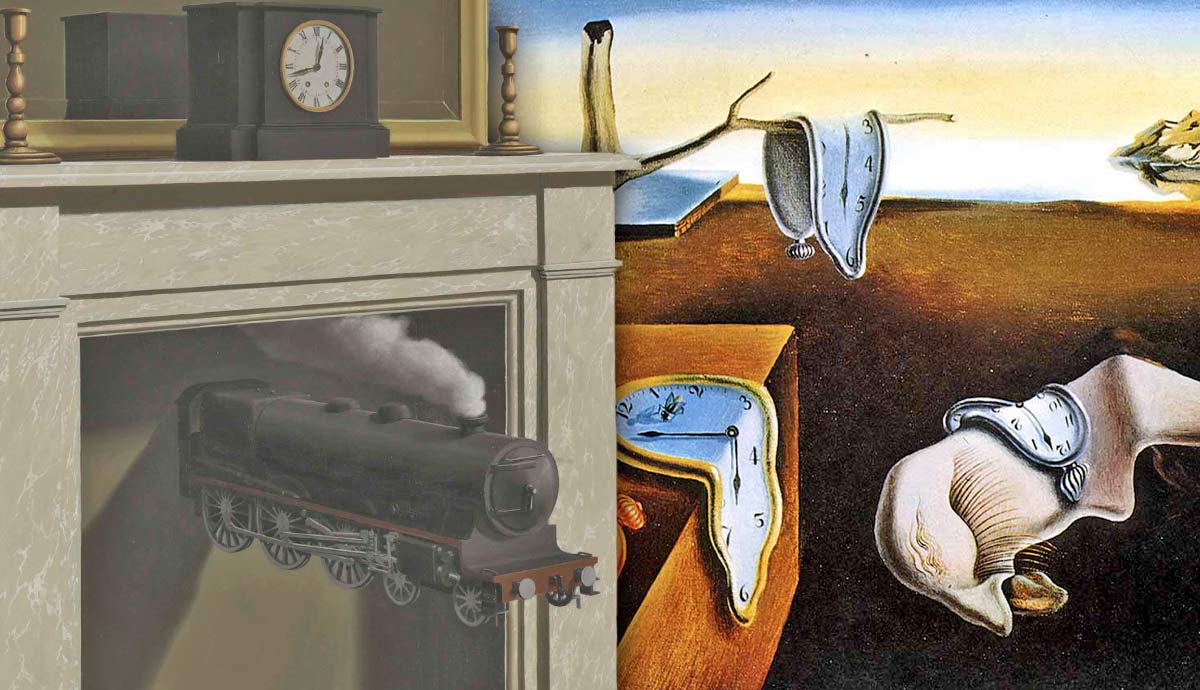

One of the first philosophers who began to think about the nature of time was Plato. The time he characterizes in his treatise Timaeus as “a moving likeness of eternity.” For Plato, time is a characteristic of an imperfect dynamic world, where there is no good but only the desire to possess it. Time thus reveals a moment of incompleteness and inferiority. Eternity, on the contrary, is a characteristic of the static and perfect world of the gods.

Aristotle further developed this understanding of time, defining it as a “measure of movement.” This interpretation was enshrined in his Physics, and it laid the foundation for the natural sciences’ understanding of time. He raises the question of evidence of the existence of time and reproduces a dialectical approach here: the past no longer exists, the future does not yet exist, and the present is the moment of the unity of being and non-being.

This dialectical approach led Aristotle to study the connection between time and motion. The thinker showed that time, although not identical to movement, is nevertheless inseparable from movement. Aristotle defines time as “the number of motions in relation to the past and the future,” and as a “measure of movement and rest.”

Later, at the beginning of the Middle Ages, Augustine developed the concept of subjective time. He described time as a mental phenomenon of changing perceptions. Augustine distinguishes three parts of time: present, past, and future.

Newton Vs. Einstein

Over the past hundred or so years, a real revolution has taken place in the scientific understanding of time. Indeed, until the beginning of the 20th century, physics and everyday consciousness were dominated by Isaac Newton’s postulate of absolute mathematical time.

According to it, time flows at the same speed throughout the universe and is in no way dependent on physical or any other processes that occur in it.

For example, if it’s six in the evening in good old England and it’s time to drink tea. This means that somewhere in the Andromeda nebula, thousands of light-years away, it’s also six in the evening! This understanding of time fits well with our everyday experience; it’s intuitive.

That is why the special theory of relativity, developed in 1905 by Albert Einstein, was a real shock for the scientific world. Its presentation goes beyond the scope of this essay, so we will emphasize only a few key points.

Firstly, according to this theory, time does not exist in isolation but forms a single whole with space (hence the expressions “space-time” and “space-time continuum”).

Secondly, time, like other physical quantities, is relative, and so the speed of its flow depends on the reference point. That is, in an object that moves (for example, in a spaceship), the clock will run slower than in a stationary one. However, such so-called relativistic effects are significantly manifested only at speeds close to the speed of light in a vacuum (about 300 thousand kilometers per second), which is considered limiting in the theory of relativity.

Hence, for example, the well-known twin paradox: when one of the twin brothers goes into space on a ship and spends a couple of years there, flying at near-light speed, after returning home, he can see that entire decades have already passed on Earth!

But Einstein’s trampling of Newton’s theories did not stop there. Newton’s law of universal gravitation assumes an infinite rate of propagation of the gravitational force. However, based on the postulate about the limit of the speed of light, which we have already mentioned, this is impossible. Because of this, Einstein had to develop his own theory of gravity, which grew into the general theory of relativity.

With regard to time, its conclusions are perhaps even more impressive than those of the special theory. Time, it turns out, is inextricably linked not only with space but also with matter! In particular, the gravitational force of physical bodies is able to slow down time again, and if gravity is strong enough, it can even…stop it! The latter phenomenon is characteristic of so-called “black holes”—cosmic objects that are the last phase of the evolution of massive stars. Interesting is also Einstein’s debate with Henri Bergson over the nature of time. Bergson thought that Einstein’s conception of time was incomplete and made a distinction between “lived time” (the subjective experience of duration) and “clock time” (Einstein’s)

Immanuel Kant’s Theory of Time

In the world of philosophy, Immanuel Kant was a pretty big deal when it comes to our understanding of time. He believed that time wasn’t something that just existed on its own, but rather it was a feature of the mind. Think of it like this—your brain doesn’t just reflect the world around you in a perfectly accurate way; instead, it organizes everything into different categories so you can understand what you’re seeing. And one of those categories is time. So for Kant, time isn’t some concrete thing that’s just out there; instead, he saw it as an “empty form,” which might sound kind of weird and unintuitive at first.

But let us explain—somewhere in your brain, a “time-keeping” mechanism helps us see things as happening within a specific timeline. Without this mechanism, we might not be able to make sense of events in the same way—everything would just be happening all at once.

But maybe you’re thinking: “OK, so Kant thought we create time with our minds—why does that matter?” Well, here’s another thing he believed: when we think about time (and space, too), we’re not just passively observing the world around us—we’re actively engaging with it through our thoughts and experiences.

To put it another way, imagine you’re at a concert. The music plays on stage, and you experience each song as happening one after another. But suppose your best friend was also at the concert but sitting in a different section than you were. In that case, they’d have a totally different experience because they would hear and see everything differently thanks to their unique perspective. This is kind of how Kant sees time, too—everyone experiences things slightly differently based on how their minds process information.

So while Newton might have approached time more like an objective universal law of nature, Kant saw it more as something that was constantly being shaped by our own thoughts and actions.

Past, Present, Future: The Dimensions of Time

Let’s start with the past. For some philosophers (like Hegel), the past is something that’s already happened and can’t be changed. It’s like a book that’s already been written—you can’t go back and erase or rewrite what happened in it.

Others (like Nietzsche) saw things a little differently—they believed that the past isn’t set in stone; instead, how we remember it changes depending on our current situation and perspective.

The present is where things get tricky: some modern philosophers don’t think that time actually exists at all! Instead, they believe that everything is happening all at once (kinda like watching a movie frame-by-frame), but our brains process everything as if it were continuous time.

Then others see the present as an important moment for making decisions that will shape our future.

The future is like looking into a crystal ball; even though nobody knows what will happen next, every action taken in both real life and fiction paves the way toward an unknown tomorrow.

Some philosophers (like Heidegger) thought that the future was something we could sort of “reach out and grab” by making choices in the present—like reaching for something today that will help us tomorrow. Others believe in a more fatalistic view, where the future is predetermined, and we’re all just along for the ride.

So, What Is the Concept of Time in Philosophy?

When it comes to philosophy, time has been explored from all angles: past, present, future, and everything in between! But through all these different schools of thought, there are a few key things we can say for sure about what time actually is (and isn’t).

First off, most philosophers agree that time isn’t some kind of universal force. It’s not like gravity or electricity—you can’t measure it the same way you can measure distance or speed. Time doesn’t exist independently; instead, it’s more like a tool we use to make sense of the world around us.

Some philosophers think that time might be an illusion altogether—sort of like how a mirage in the desert appears to be real even though it’s not really there. Instead, they believe that everything is always happening at once, even though that’s not how it seems to us.

Other philosophers see time as an essential part of human experience—something that shapes our memories and connects us. Think about it: without shared ideas about what time means (like “day” or “year”), how would we organize ourselves as a society? How would we know when to start school or work? So in this way, time is both a personal and social construct.