Picasso was fascinated by the monstrous half-man, half-bull Minotaur of Greek mythology. So much so, this terrifying and brutal character became a recurring feature in his art from the 1920s all the way to his later years in the 1950s, appearing in around 70 different artworks. But what was it about this ferocious, mythological monster that so captured his imagination? And why did Picasso feel such a close affinity with the Minotaur? In order to understand, we need to delve a little deeper into the artist’s life and work.

Picasso Saw Aspects of Himself in the Minotaur

Picasso saw many aspects of his own identity in the Minotaur. In 1960, he even said “If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line, it might represent a Minotaur.” For one, Picasso likened the Minotaur’s bull qualities to the bullfighting of his native Spain. When he was a young boy, Picasso made an obsessive series of drawings featuring matadors and bulls, demonstrating his early fascination with the fear and splendor of this Spanish tradition. He returned to this same theme as an adult, sometimes including the Minotaur as a powerful symbol of man versus beast.

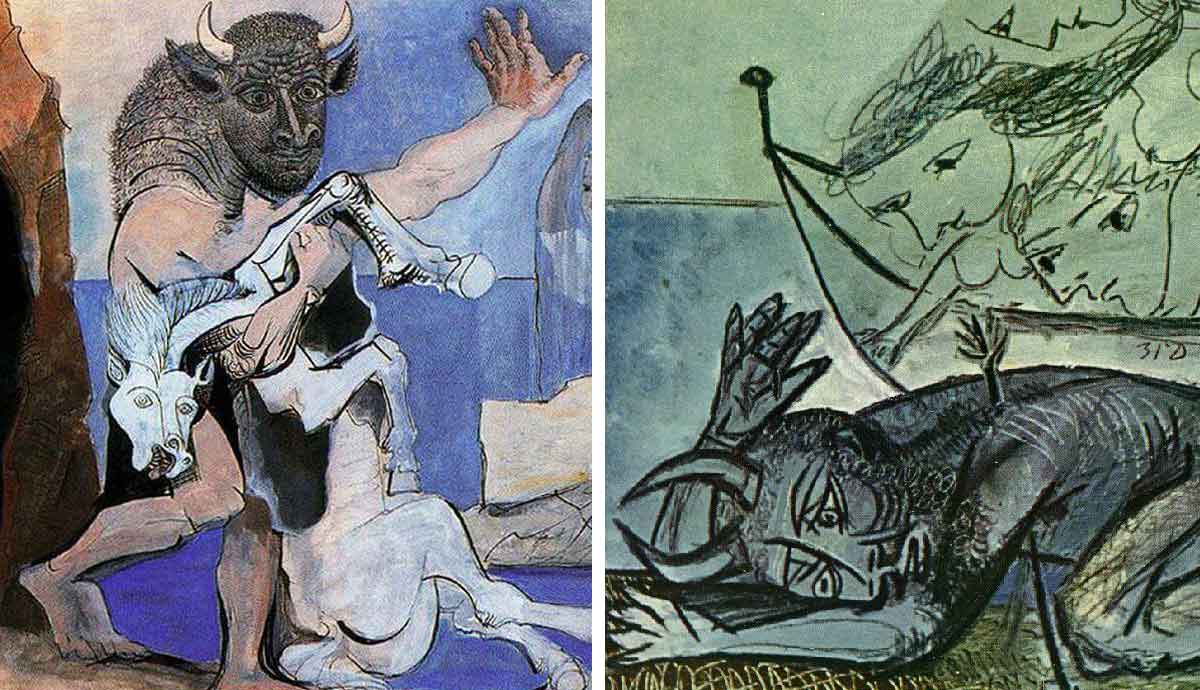

Picasso also saw aspects of his own character in the Minotaur. He likened the Minotaur’s raging masculinity and physical strength to his own virile qualities – he was, of course, known for being an incorrigible womanizer. So, many times when he depicts the Minotaur as a tangled mass of curly hair and horns, as seen in the etching suite La Suite Vollard, 1935, he is also, to some degree, making a self-portrait. In other artworks Picasso emphasizes the Minotaur’s underlying vulnerability, which we see in Minotaur Est Blesse, 1937, thus sharing with us some of his own feelings of insecurity lurking beneath the bravado.

Picasso and the Minotaur: An Expression of Irrationality and the Unconscious Mind

Picasso became particularly enamored with the mythical figure of the Minotaur during the late 1920s and 1930s. During this decade Picasso began his Neoclassical period, abandoning Cubism for classical and mythological subject matter. Throughout this time, Picasso worked closely alongside the French Surrealists, and their ideas about dreams and the subconscious undoubtedly fed into his Neoclassical art.

In particular, Picasso saw in ancient subjects a way of expressing the powerful irrationality of the unconscious mind, through potent and emotive symbolism. Picasso created a stirring collage featuring the Minotaur for the first cover for the Surrealist magazine Minotaure in 1933, emphasizing the beast’s solid, muscular form. Later, in 1935, Picasso produced an intensely detailed etching titled Minotauromachie, 1935. He made this etching during a particularly turbulent time in his personal life, when his wife Olga Khokhlova was on the verge of leaving him after discovering he had made his young mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter pregnant. His wild emotions spill out in this fictional, narrative tale, with the Minotaur at the center as a stirring symbol of feelings spiraling out of control.

A Symbol of Political Dissent

During the 1930s, Picasso became increasingly angered by the rise of fascism. For the first time in his career, he began to use his art as a tool for expressing ideas around political dissent and disorder. Thus, the bull, and the Minotaur, appeared as a symbol of freedom-fighting and rebellion in the face of an attack. In Picasso’s Guernica, 1937, the most daringly political artwork he would ever make, the artist includes a bull’s head to the left, which closely resembles his earlier depictions of the Minotaur. Interpretations of the Minotaur-like creature in Guernica vary, but some see it as a symbol for Picasso himself, watching from afar with painful despair as the horrific war crime unfolds before him.