In one of his Letters, Pliny the Younger describes the only known instance when the Roman Senate was forced to vote between three alternatives, instead of making the usual binary choice. Three factions were formed, each of them favoring a different outcome. Pliny’s faction had the most supporters, but not the absolute majority, while the other two factions were preparing to form a coalition. To prevent such an outcome, Pliny, who presided over the meeting, decreed that all three outcomes should be voted on simultaneously. Was Pliny simply trying to rig the vote? Or was he on the verge of discovering some curious features of collective decision-making?

Pliny the Younger and His Letters

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, commonly known as Pliny the Younger, was a prominent figure in ancient Rome during the first century CE. He owed much of his influence and inspiration to his uncle, Pliny the Elder, a renowned naturalist and author. Pliny the Younger’s life was marked by significant events and accomplishments, as well as his exceptional skill in letter writing. One of the defining moments in Pliny the Younger’s life occurred when he was just eighteen years old. He personally witnessed the catastrophic destruction of Pompeii, where his uncle tragically lost his life during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. This experience undoubtedly had a profound impact on him and shaped his worldview.

Pliny the Younger quickly rose to prominence in Roman society, establishing himself as a distinguished prosecutor and defender of public officials. His legal prowess and dedication to justice earned him a high position within the civil service hierarchy. Moreover, his talent for financial matters made him an efficient administrator who contributed to the smooth functioning of the Roman state. In the later years of his life, Pliny the Younger was appointed as the governor of the Roman province of Bithynia-Pontus, located in modern-day Turkey. As a skilled diplomat, he successfully navigated the complexities of Roman political life and survived the rule of three different emperors. Pliny the Younger’s reputation as an honest and capable public official earned him respect and admiration among his contemporaries.

However, Pliny the Younger’s enduring legacy lies in his prolific letter-writing. He meticulously crafted numerous letters, of which about 300 hundred have survived to this day. These letters provide valuable insights into the everyday life of the Roman Empire during the first century CE. Pliny made letter-writing an art form (Szpiro, 2010). In them, he addressed not only the intended recipients but also a wider audience. It is apparent that he intended to publish his letters eventually so that he could share his knowledge and experiences with a broader readership. Each letter often focused on a specific question or topic, allowing Pliny to delve into various aspects of Roman society, politics, and culture. Through his correspondence, we gain a vivid and intimate understanding of life in ancient Rome, as well as the challenges faced by its inhabitants.

The Mysterious Death of Afranius Dexter

One of the many letters penned by Pliny the Younger addressed to his close friend Titus Aristo (VIII, 14), reveals a mysterious account that continues to puzzle readers: the death of Afranius Dexter, a distinguished Roman senator and former consul. On the fateful day of June 24, 105 CE, Dexter’s lifeless body was discovered within the confines of his own home and left behind a trail of unanswered questions (Szpiro, 2010).

The circumstances surrounding Dexter’s demise remain cloaked in ambiguity since Pliny’s letter fails to provide details about the discovery of the body, the nature of the weapon used, and whether any evidence was found at the scene. What is certain, however, is that Dexter met a violent end. In the absence of concrete evidence, three possible scenarios emerged. The first suggests that Dexter may have taken his own life. The second possibility is that members of Dexter’s household might have committed a foul murder. The third, and perhaps the most interesting possibility, is that Dexter, lacking the will to end his own life, ordered others to carry out the act.

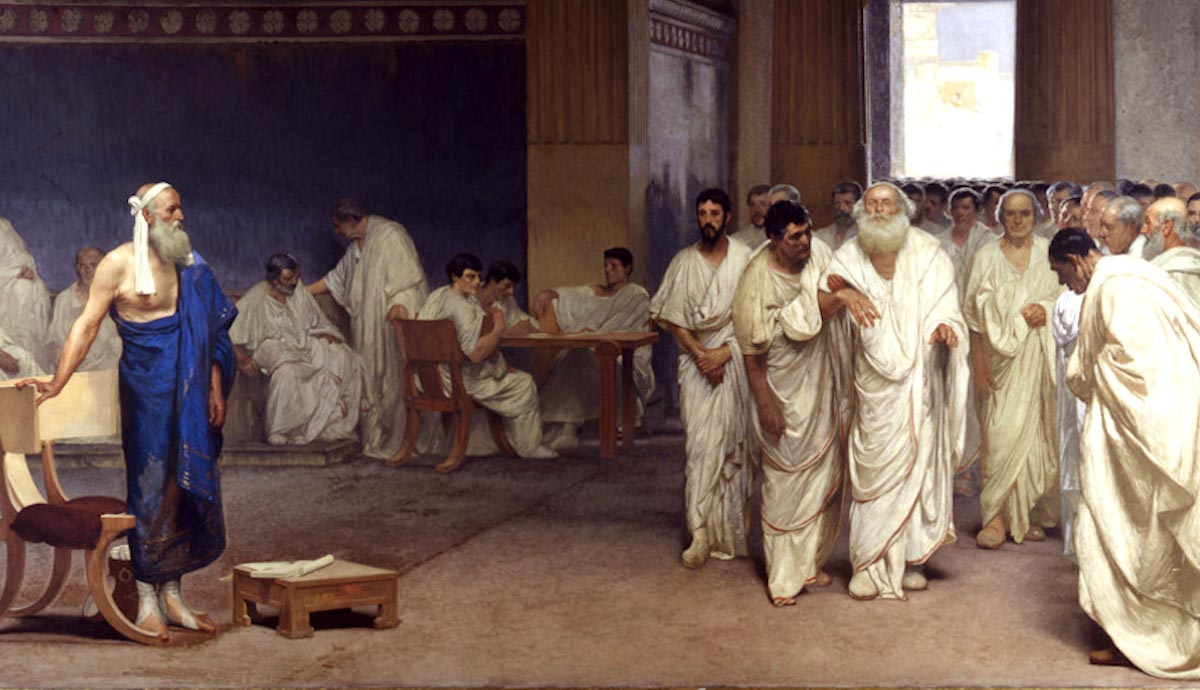

The investigation naturally focused on Dexter’s freedmen, as they were the only individuals with the means to commit the crime–if indeed it was a crime. According to Roman law, killing one’s master was punishable by death. However, if the freedmen were innocent, they should be granted their freedom. But if Dexter himself had indeed commanded them to kill him, they may bear partial guilt. Since the authorities were unable to ascertain the circumstances surrounding Dexter’s death, the matter has been brought before the Senate. Pliny, who presided over the Senate meeting, provides us with a firsthand account of the ensuing events.

The Divided Senate: Acquittal, Banishment, or Execution

In the Senate, the death of Dexter led to the formation of three distinct factions, each advocating for a different sentence. The first faction argued for the acquittal of the freemen, believing that if Dexter’s demise was indeed a result of suicide, they should be absolved of any guilt. The second faction proposed banishment to an island – presumably, the senators favoring this option believed that Dexter had ordered his servants to end his life and as such, they were only partially guilty. The third faction called for the death of the freedmen. Their argument rested on the assumption that if the servants had murdered Dexter of their own accord, they should bear the full weight of the law.

As a result, the Senate faced a ternary choice: acquittal, banishment, or execution. Unlike the modern-day legal system, where courts typically reach a verdict before pronouncing the sentence, the Senate did not make such a division. The verdict and the sentence were not separate; by pronouncing the sentence, the senators implied the verdict. However, two of these options (banishment and death) implied guilt for the freemen, while the third implied their innocence. At the same time, two options (banishment and acquittal) would spare the freemen’s lives, while the third would see them killed.

In a binary choice, one option always wins the majority support. However, with three or more options, this is not necessarily the case, and that’s exactly what happened in this situation. According to Pliny, who belonged to the acquittal faction, they had the most support but not the absolute majority, while the other two factions were roughly equal in size.

We can presume that the first option had approximately 40% support from the senators, while the remaining two had around 30% each. This created fertile ground for manipulation, and Pliny, being a skilled diplomat, seized the opportunity. He cunningly advocated for a course of action that would serve the interests of his faction, but his troubled conscience began to weigh on him afterward. It was this internal turmoil that compelled Pliny to seek Aristo’s opinion on whether he had overstepped his boundaries.

Pliny’s Proposal for Simultaneous Decision

Pliny did not raise any questions concerning public law. Instead, his primary concern lay in the procedural issues surrounding the matter at hand. As the debate progressed, it became evident that most senators leaned towards acquittal among the three available options. Consequently, the proponents of the other two factions decided to join forces and form a coalition. In the Roman Senate, it was customary for senators to physically move from their seats and gather on one side of the Senate chamber, aligning themselves as a unified group. This practice allowed for a swift determination of numerical advantage, obviating the need for an actual vote. In this case, the larger group, comprising approximately 60% of the senators, held the view that the freemen should not be acquitted.

Pliny contested the legitimacy of such a coalition. He argued that the division among the senators should not align with the distinction between guilty and non-guilty. Pliny expressed this sentiment by stating that the execution was roughly as far removed from banishment as banishment was from release. Consequently, it seemed highly unreasonable to him that those favoring banishment would align themselves with those advocating for the death penalty. If there must be a coalition, he claimed it would be more natural for the banishment faction to ally themselves with the acquittal faction. Nevertheless, he defended the idea that no coalitions should be formed since each option represented a distinct choice in itself.

Given the customary practice of senators sitting with those who shared their preferred option, Pliny, as the presiding authority, made an unprecedented request. He called for the senators to sit in three separate locations, reflecting the three available options. Essentially, Pliny sought a simultaneous decision on all three choices — a novel approach in the Senate. To support his stance, he referenced the law stipulating that senators should vote according to their honest convictions, thereby disallowing contrived coalitions. It was precisely due to this concern that he reached out to Aristo, seeking his opinion on whether such actions were lawful or if he had overstepped his role as chairman. Unfortunately, the response from Aristo remains unknown.

Pliny the Younger: Manipulation of the Agenda or a Profound Discovery?

Pliny, however, was well aware that his proposal favored his own faction and would likely lead to their victory. He believed that in a three-way vote, the relative majority supporting the acquittal of the freemen would prevail due to their larger vote count. Pliny anticipated that the members of the other two factions would remain in their separate corners. However, it appeared that he had underestimated his opponents. The leader of the faction advocating for execution discerned Pliny’s plan and once again aligned himself with the banishment faction, rallying his allies to do the same. Consequently, even with Pliny’s revised procedure, the 60% majority of senators ultimately voted in favor of banishment.

Was Pliny justified in acting as he did? Undoubtedly, he tried to manipulate the agenda to ensure the victory of his preferred option. Such an act was clearly wrong from a procedural point of view. A ternary choice can be a legitimate way to make a decision, but only if it was agreed upon in advance. Making up a procedure while the meeting is ongoing was a wrong move on Pliny’s part.

However, Pliny did not claim that choosing between three options should be allowed no matter what. He provided reasons for his decision, based on the relationships between the options themselves. Specifically, he maintained that a ternary choice was a preferred way of making a decision only because the three options are so distinct that no option can be considered subordinate to another. He claimed that the option of banishment sits perfectly between acquittal and execution. What Pliny meant to say is that a rational individual could form their opinion on the three options only in a certain way.

Those who favor acquittal the most must also prefer banishment over execution, while those who prefer execution must prefer banishment over acquittal. As for those who preferred banishment, they could prioritize the remaining two options in either order (depending on whether they felt more strongly that the freemen should be punished or that they should be left alive). In more technical terms, Pliny recognized that said options formed a continuum. In other words, this is likely the first time in history that somebody stumbled upon the notion of single-peaked preferences. In fact, the idea that only when individual preferences are single-peaked, a choice between three or more options is viable, became prominent only in the twentieth century (Black, 1998).

Pliny’s attempt to manipulate the agenda in the Roman Senate was a procedural misstep that ultimately failed. However, his claim that ternary choice is viable only when individual preferences form a continuum was a profound insight ahead of its time. Pliny’s actions may have been flawed, but his exploration of decision-making dynamics sheds light on the concept of single-peaked preferences, a notion that gained prominence much later in history.

Bibliography

Black, Duncan (1998). The Theory of Committees and Elections. New York: Springer Science.

Szpiro, George G. (2010). Numbers Rule: The Vexing Mathematics of Democracy from Plato to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press.