Today, we frequently hear that we are in unprecedented times when it comes to politics and voting. But is that actually the case? Are there historical parallels and precedents to today’s political landscape? Over time, voter turnout and political ideologies have evolved in the United States, influenced by economic, infrastructural, social, and international factors.

We will explore whether we are more active voters today than in previous generations or whether our modern concepts of terms like “liberal,” “conservative,” “progressive,” “socialist,” or “radical” mean the same thing they used to. From the early republic to the 21st century, how have voter turnout and political ideologies shifted and evolved?

Setting the Stage: Limited Suffrage

When looking at voter turnout and political ideologies, we are somewhat limited in the early republic era (1780s-1810s) because most Americans were unable to vote. Suffrage was limited to white, property-owning, and tax-paying men aged 21 or older. This meant that only the wealthy, or at least upper-middle-class, could officially vote during the first few decades of the United States. There were also religious tests in some states to ensure that only Protestant men could cast ballots. Therefore, out of the entire population, political activism was extremely limited.

One concern in the early republic was not to disenfranchise (block from engagement) those in rural areas. This led to the creation of the Electoral College for presidential elections and equal representation per state in the new US Senate in the United States Constitutional Convention of 1787. Many Anti-Federalists were initially concerned that rural areas would automatically lose political power to more-populated urban centers and thus opposed giving more power to a central government. The Constitution was ratified by states in 1789, and its two major concessions to smaller and more rural states definitely improved voter turnout among rural Anti-Federalists.

Setting the Stage: Voting in the Early Republic

Despite the two major concessions granted to smaller and more rural states in the Constitution, voter engagement and turnout remained relatively low in the first several federal elections. The Federalists and Anti-Federalists remained active after the ratification of the Constitution, with the new political battleground being economic policies. The Federalists supported the policies proposed by Alexander Hamilton, who wanted more centralized, government-guided economic activity focused on urban development. Anti-Federalists rejected this and feared government meddling in the economy, which could hurt agriculture prices.

Voter turnout was difficult to determine before the mid-1820s but was likely reduced due to the complexity and confusion of election rules. Because elections were the domain of the states, different states often had different rules regarding who could vote, when they could vote, and how they could vote. Additionally, travel was more difficult during this era, making it hard to travel to cast a ballot. As a result, even those who were eligible to vote and had registered to vote did not exercise it regularly. Finally, many “common” voters believed that politics was for the wealthy and well-educated and thus did not seek to vote actively until the populist era of the mid-1820s under Democratic candidate Andrew Jackson.

Who Voted More? Partisan Differences in the Pre-Civil War Era

The Federalists and Anti-Federalists quickly evolved into new political parties. The Anti-Federalists became the Democratic-Republicans, who became known simply as Democrats. The Federalists eventually became the Whigs, who collapsed and re-emerged mostly as Republicans. The 1860 election was the first presidential election to feature the two major political parties we know today: the Southern and agrarian Democratic Party and the Northern and urban Republican Party. At the time, the two parties held virtually opposite platforms and cultures compared to today.

Voter turnout, especially within the Republican Party, drastically increased in the years leading up to the American Civil War. One reason was the intensity of the political issue of the era: slavery. Thanks to the Second Great Awakening of the 1830s and early 1840s, many abolitionists felt that slavery was an ethical and moral wrong. A second reason for high voter turnout was the rise of political machines in urban areas. Political leaders in cities had strong motivation to turn out voters: winning elections allowed these leaders to control government jobs and funds under the spoils system that gave rarely-checked power to elected executives.

1865-1929: Republican Dominance Era

In 1860, Republican presidential nominee Abraham Lincoln won the election by dominating the vote in populous Northern states. Seeing Lincoln’s victory as a political death knell, the South seceded from the union and formed the Confederate States of America. Lincoln held the union together by force, with the United States defeating the Confederacy after four years of hard combat. The Democratic Party, which had been dominant in the agrarian South, lost virtually all power outside the former Confederacy. Lincoln’s Republican Party became nationally dominant in the aftermath of its victory in the Civil War.

Voter turnout was initially very high after the war, likely fueled by post-war political drama as the South attempted to return to its old ways, and Radical Republicans in Congress had to continually legislate requirements to ban the suppression of formerly enslaved people. A wave of populism in the early 1890s kept Democratic voter turnout high until after 1896 when the solid Republican defeat of populist Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan dashed the hopes of low-income Democrats in the South, most of whom were farmers. It seemed that urban Republicans would always dominate national elections.

1930-1948: Democratic Dominance Era

The stock market crash of 1929 triggered the Great Depression, which resulted in traumatic bank failures and waves of unemployment. Republicans had dominated most elections since the Civil War but were now facing an angry public that had swiftly turned against laissez-faire economics. Conservative Republican US President Herbert Hoover did not believe it was the federal government’s role to provide direct aid to the homeless and unemployed…and he was swamped by a Democratic landslide in 1932. The Democratic presidential nominee, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, had promised Americans immediate action to help stabilize the economy.

Voter turnout had been falling steadily since 1896 but began an upward trend again in 1930 as angry voters wanted a change in political leadership. Roosevelt lived up to his campaign promises and launched his New Deal initiatives immediately upon taking office. This led to another landslide victory in 1936, buoyed by high voter turnout, as voters wanted a guarantee of continued Democratic economic policies. Voter turnout, most of which was Democratic as millions of voters shifted their party allegiance, climbed through 1940. Although Roosevelt and the Democrats remained dominant through the end of World War II, voter turnout declined after 1940 due to the distractions of war.

1950-1962: Moderate Era and Liberal/Conservative Consensus

While voters had rallied in the early 1930s to protect their economic interests, would they remain engaged politically during the post-war economic boom? Voter engagement actually increased again during the 1950s after a post-war slump. Some attribute this to both major parties using television to advertise to voters in a way that had never been done before. Between 1952 and 1960, voter turnout among both parties increased due to heavy political advertising and the political drama of the Cold War: Americans were encouraged to be patriotic and exercise democracy to contrast with the communist Soviet Union.

Voter turnout during this era peaked in 1960 when both major party nominees were young men with similar views. Part of the peak may have been due to the famously televised debate between Democratic presidential nominee John F. Kennedy and Republican nominee Richard Nixon, who were considered evenly matched. The even match may have increased voter turnout due to competition—either candidate seemed capable of winning, and anyone’s vote could swing the difference. Kennedy narrowly won the election and became president, and his seeming geopolitical victory during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 helped boost Democratic turnout in that year’s midterms.

1964-1976: Civil Rights to Stagflation: Tensions Rise

The Democratic surge of 1962, boosted by Kennedy’s victory in Cuba, continued in 1964 when incumbent US president Lyndon B. Johnson (Kennedy’s replacement after the tragic 1963 assassination) trounced ultra-conservative Republican nominee Barry Goldwater. However, voter turnout as a whole decreased in 1964, likely due to Johnson appearing to have a significant popularity advantage over Goldwater. Voter turnout fell between 1964 and 1988, likely due to multiple factors. Many voters may have felt disengaged or alienated due to America’s turmoil over Civil Rights and Vietnam in the mid-to-late-1960s.

After the end of the Civil Rights Movement in the late 1960s, the economic malaise of the stagflation era between 1973 and the early 1980s may have also disengaged and alienated many voters, regardless of political ideology. Up through the early 1960s, voters likely felt more impassioned about pressing issues like civil rights and the possibility of nuclear destruction. By the 1970s, however, issues were more mundane and had less clear moral and ethical answers. Thus, neither liberals nor conservatives felt highly motivated to take the time to vote—lives did not seem to be on the line, and answers to creeping questions like environmental degradation, foreign competition, and inflation were less clear-cut.

1980-2004: Reagan Revolution and 9/11 Make America More Conservative

Despite the improving economy by 1984, under popular conservative figure Ronald Reagan, voter turnout remained lower. It is possible that Democrats and ideological liberals felt disempowered by the seeming success of Reaganomics and thus neglected to vote in 1984 and 1988. Voter turnout in the modern era reached its lowest point in ‘88, when Reagan’s vice president, George Bush Sr., was poised to inherit a strong US economy and geopolitical victories from a crumbling Soviet Union. The Cold War was all but won, and Americans credited Reagan/Bush.

Voter turnout began to increase again in 1992 when incumbent president Bush faced a strong challenge from Democratic nominee Bill Clinton. Despite a peak in popularity upon winning the Gulf War in February 1991, Bush saw his appeal crumble later in the year due to an economic recession. Clinton appealed to liberals, especially young liberals, and boosted their turnout in 1992. A popular third-party candidate, Texas billionaire Ross Perot, also boosted voter turnout by appealing to independent voters who did not pledge (strong) support to either major party. Although Clinton won the White House, Republicans quickly controlled Congress, setting the stage for an era of ideological moderacy in government. Conservatives in Congress, and later the White House under George W. Bush, tempered normal liberal policies and shifted overall American politics more toward conservatism.

2008-Present: Multiculturalism Re-Intensifies the Partisan Divide

Voter turnout was relatively low in 1996 and 2000, thanks to peace abroad and prosperity at home. In 2004, however, the US wars in Afghanistan and Iraq impassioned voters once again. Conservatives kept the White House in 2004, aided by strong appeals to patriotism and national security. Four years later, however, a new political era was dawning with the emergence of the first nonwhite presidential nominee: Democratic candidate Barack Obama, the young US Senator from Illinois. In 2008, voter turnout spiked to 60 percent for the presidential election, which Obama won.

The rise of America’s first nonwhite president was seen by many as heralding a new era of liberalism. Allegedly, hostility to Obama influenced a backlash among many white conservatives, who populated the Tea Party Republican movement of 2009-2012. Although voter turnout waned in 2012, likely due to some healing of the Great Recession (2008-10) under Obama’s administration, it spiked again in 2016 when the first female presidential nominee, Democrat Hillary Clinton, ran for the White House. Many liberals, especially women, felt empowered by the first female major party nominee. Conversely, many conservatives, especially men, allegedly felt motivated to oppose Hillary Clinton.

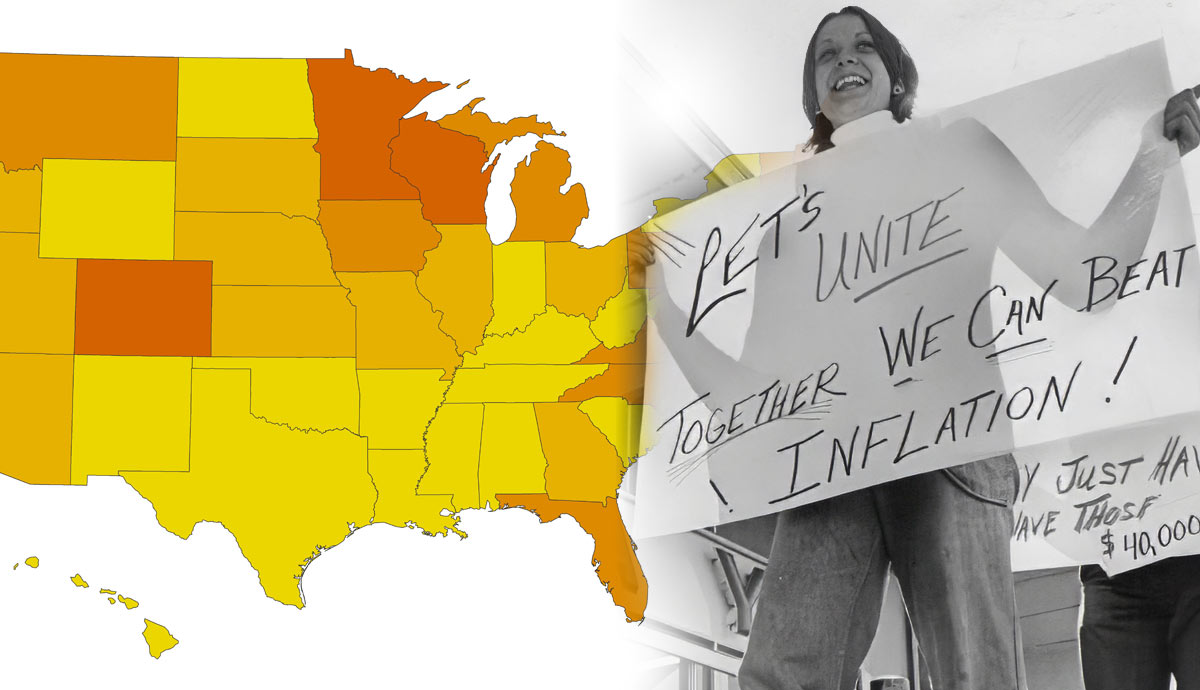

2021-Present: Inflation Woes and Fears of Tyranny Affect Voter Turnout

Hillary Clinton won the nationwide popular vote in 2016 but lost the Electoral College to Republican rival Donald Trump. In 2020, voter turnout increased again due to economic woes—the Covid pandemic had caused a brief but intense economic recession. Democratic nominee Joe Biden, vice president under Barack Obama, won the White House. Months into Biden’s term, prices began to rise as the United States was beset with soaring inflation. By June 2022, inflation had peaked at 9.1 percent, the worst since the era of stagflation. Voters of all ideologies were upset with the high costs of living.

This economic pain helped keep midterm voter turnout high in 2022, almost as high as in 2018. Conservatives voted in large numbers to reject the economic policies of the Biden administration, which they blamed for the high inflation. Liberals voted in similarly large numbers to reject the candidates and policies championed by former Republican president Donald Trump, who was seen by many as tyrannical. Ultimately, the 2022 midterms surprised analysts by resulting in a virtual tie: Republicans only won the House of Representatives by a very thin majority, while Democrats actually increased their control of the Senate by a seat.