Folklore, the traditions passed by word of mouth through the generations in a particular place, is immensely important in establishing local identity and community. The way these narratives shift and take on new societal ideas can reveal so much about how people feel, and their attitudes to what has happened to them as a group. These stories continue to be significant, particularly in relation to gender politics, colonialism, and the natural world. Here are ten stories about powerful women from different cultures.

1. Scheherazade

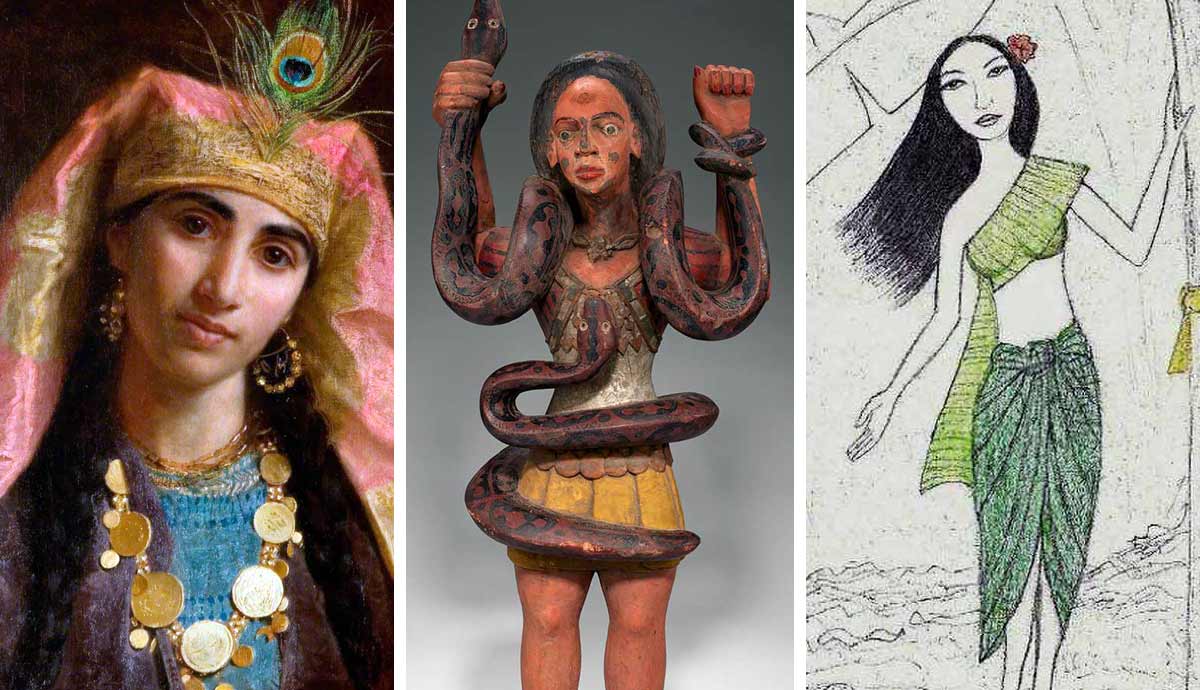

Scheherazade is an important character from One Thousand and One Nights, a collection of folktales from the Middle East and Asia from the Islamic Golden Age. One Thousand and One Nights is famous worldwide for characters such as Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sinbad, who remain household names to this day. Scheherazade, however, often does not receive the same attention despite her role being central to the narrative.

In the story, the sultan Shahryar discovers that his wife has been unfaithful and has her executed. In addition, he blames all women and decides to marry a new woman each day and then have her executed the following day. After three years of this, a vizier of the sultan is shocked to see his daughter, Scheherazade has offered to marry Shahryar.

On the night of the wedding, Scheherazade asks to say goodbye to her younger sister who joins the couple, and subsequently asks for Scheherazade to tell her a story. While Scheherazade is in the middle of her tale, she realizes it is now daylight and apologizes for taking so much time, however, the sultan wants to know the ending and allows her to keep going.

This pattern continues for one thousand and one nights until she runs out of stories to tell. Yet during this time Shahryar falls in love with Scheherazade, ends his regime of marrying and executing wives, and makes her his queen.

Therefore, Scheherazade manages to use her intelligence to save her life and the lives of other women and she is incredibly brave for putting herself in direct danger by offering to marry the sultan. Hence, she becomes a powerful role model for women outside of the typical traits of beauty and submission.

2. La Diablesse

Translated into English as the “she-devil,” this Caribbean enchantress is infamous for luring men to their deaths. The story of La Diablesse can be found all over Trinidad, Tobago, and Grenada where she is said to have sold her soul to the devil for timeless youth and beauty.

La Diablesse is supposedly a tall, beautiful woman and men are so hypnotized by her presence that they often do not notice her cow’s hoof foot on one leg and her scent of decay. While she poses no threat to women or children there are countless stories of the ways that she lures men to their deaths.

In some traditions, La Diablesse is a seductress who bewitches men in bars who then follow her into dark and isolated areas of a forest or wood voluntarily. In other versions of the folklore, the presence of La Diablesse drives men to the point of madness, so that they fall into rivers, get so lost that they never return, or are even eaten by wild dogs.

Several local communities have their own slight variations on the tale, for example, some say she only appears in daylight while others say only during the full moon. Most agree that the way to break her charm over you is to turn your clothes inside out and walk away backward or you can light a match which should make her vanish.

The story has traditionally been associated with discouraging infidelity among men and dissuading them from drinking too much and partying. It can also be interpreted as being a story that warns people of the dangers within forests and woodland areas.

3. Grýla

The Ogress of Iceland, the Grýla originates from the 13th century and by the 17th century, was combined with local Icelandic Christmas traditions. Throughout the year she makes a list of badly behaved children, then on Christmas Eve she gathers them in her sack, brings them back to her cave, and eats them in the form of a stew. This stew is supposed to feed Grýla and a host of housemates she shares her cave with until the following Christmas.

According to Grýla’s backstory, she has already killed her first two husbands (having eaten the first) and now lives with Leppaludi, her third husband. Also in the cave are the Yule Lads, thirteen trolls who are usually described as Grýla and Leppaludi’s children.

The Yule Lads do everything from getting into mischief to tormenting locals and each is named after their favorite form of harassment, such as Bjúgnakrækir which translates to Sausage Swiper who hides in the rafters waiting to steal smoked sausages, and Þvörusleikir which means Spoon Licker who unsurprisingly, steals wooden spoons. Finally, Grýla also lives with the Yule Cat who eats children who did not receive new clothes for Christmas Eve.

The story of Grýla has been used as a cautionary tale to warn of extreme and powerful weather conditions in Iceland, particularly in winter, as well as to incite good behavior among children. Moreover, Grýla and her family are particularly scary because they subvert traditional family dynamics.

4. Cihuateteo

The Cihuateteo come from Aztec mythology and are the spiritual embodiment of women who died in childbirth. For the Aztecs, childbirth was seen as akin to warfare, and women who died in childbirth were equally honored as fallen warriors in battle. The respect for these deceased mothers was so great that men would often try to steal small body parts (such as fingers) to wear for bravery in battle. Furthermore, the souls of Cihuateteo and the men who died on the battlefield went to two different realms in the sky — the fallen men in the east who helped the sun to rise and the Cihuateteo in the west who helped it to set.

However, the Cihuateteo were not just viewed with respect but also feared, as mythology dictated that they would return to the land of the living five times a year and attempt to steal children as they never had a chance to raise their own. Even grown adults who came across the Cihuateteo on these days could go mad or experience paralysis. Additionally, they are commonly associated with crossroads, and offerings to the Cihuateteo would be left out at shrines by crossroads on their five specific days of descent.

The legendary Cihuateteo are routinely associated with the exploration into how perilous having children can be for both a mother and baby during the birth, and throughout childhood. The story offered families an explanation as to why children should be kept inside at night or not stray too far from home.

5. Nang Tani

Popular in Thailand, Nang Tani appears as a beautiful young woman in traditional clothes in wild banana tree groves. Animism is a key aspect of Thai culture which means that most people believe that all living things, such as animals and plants have their own individual spirits. She appears during the full moon and can be an ambivalent spirit who offers good fortune or ill luck.

Nang Tani’s purpose is disputed among locals, and she is said to be a spirit who avenges women wronged by men and also a spirit representative of the sacred banana trees which are essential for magic and medicine in Thai culture. Nevertheless, she is said to be a gentle spirit who protects the groves and bestows bad luck upon anyone who would cut down a banana tree.

In some variations of the folklore, she can be summoned by men who urinate on the banana trees and marry them, but she then drains their life force or soul during sex. Locals often tie red cloths around particular trees to signify they should not be felled unless they want to anger Nang Tani. People leave flowers and sweets near the banana trees in the hope that Nang Tai will grant them good luck.

Nang Tani represents a cautionary tale about the dangers of cutting down the sacred banana tree and explores the idea of respect humans should have for the natural world. She also characterizes the importance and power of nature which is capable of helping and harming the human population.

6. Mami Wata

A name that has gained a lot of notoriety in recent years and even a Sundance Film Festival award-winning movie in 2023, Mami Wata is both a single deity and a group of water spirits called “Mami Watas” who are almost always female.

Her origins are widely debated; while she appears across West Africa and is sometimes assumed to be thousands of years old, others suggest she comes from the time of European and American imperialism in Africa. Some suggest that her name comes from Pidgin English for “mother water” and others claim her name implies Ethiopian origins.

Historians have recently focused on less Eurocentric ideas and have suggested this folklore likely manifested on the coast of Guinea around 4,000 years ago and that a later name change could have been made to represent society during the African diaspora.

Despite her elusive origins, Mami Wata is typically depicted with the mermaid-like hindquarters of a fish or a serpent with the upper body of a woman. She possesses a deep association with combs and mirrors. She is also connected with fertility and is said to be a protector of mothers, but she can be cruel and cause infertility as a punishment if a woman is said to be too egotistical. As a protector deity, it seems unsurprising that her cult was brought by captured slaves to the Americas — it is even said that she would capsize slaving vessels.

The story of Mami Wata is especially interesting due to the additions and alterations made to the narrative taken from what was happening to the people who revered her. Mami Wata gained further associations with wealth during colonialism when Europeans destroyed local economies, and it was said that she could bestow prosperity on those who worshipped her faithfully. Folklore both warns of the dangers of water as well as its wealth. Mami Wata can be a protective benevolent spirit during periods of hardship.

7. Glaistig

From Scottish mythology, the Glaistig, or sometimes the Maighdeann Uaine (Green Lady) is a mysterious female ghost that can either lure men to their deaths or protect cattle and their herders. Although she is often said to be beautiful, many tales depict the Glaistig as having the lower body of a goat. She is a type of fairy that is usually associated with rivers and lochs (her name actually translates as “water imp” in Gaelic) and in some cases farms and castles.

The Glaistig is known to be both benevolent and malicious with many variants from local folklore all over the country. In some cases, she protects herds of deer, and she will only allow hunters to see the herd if they give her an offering. In other traditions, she has been known to throw stones to lure travelers off course and even drink their blood as some sort of succubus.

In some local tales, the Glaistig or Green Lady has been known to perform household tasks at night in exchange for small offerings of milk and there is a famous instance at Ach-na-Creige where the Glaistig leaves due to the prank of a local boy who gives her boiling milk. The Maighdeann Uaine derivative of the story shares direct comparisons to the banshee and wails when a creature associated with her is about to die. Likewise, the Green Lady is often linked back to a tradition whereby a noblewoman was cursed to possess immortality and the legs of a goat.

In the oldest known stories about the Glaistig, she is thought of as a playful spirit and friend of children. Her seemingly ambivalent nature represents the ever-changing weather conditions and power of the wilderness in Scotland, which can be both exciting and dangerous.

8. La Madre Monté

Meaning “Mother Mountain” in Spanish, La Madre Monté is a Colombian rebel spirit who manifests in a variety of ways but in most localities is considered to be a powerful friend of animals and nature. While descriptions of her range from a tall, beautiful woman to an old woman with bright red eyes to someone who is more vegetation than human, her powers over the wilderness are always renowned. It is said that she disorientates those who venture into the jungle and haunts those who wish to cause the jungle harm.

Most sightings of La Madre Monté occur within forests, however, she is typically heard and not seen. Her screams are said to be heard on stormy nights, apparently warning of danger, and they can also be heard as woodcutters fell trees.

Moreover, she is a protector of animals and plants from humans, and it is known that she erases pathways for people traveling in forests causing them to get lost. Her disdain for human presence within the forest is equally palpable as she makes people feel so dizzy, that they sit down to rest, only to wake up unaware of where they are hours later. Even children are not safe from La Madre Monté’s wrath because if they wander too deep, she will hide them behind waterfalls never to be seen again. Alternatively, she can be a friend to locals who have had their lands stolen and she enacts revenge for those who have suffered due to the impacts of colonialism.

La Madre Monté acts as a powerful embodiment of the Columbian forest and will protect the natural order against people, local or otherwise if they pose a threat. The narrative correlates to the importance of the forests and wildlife for locals as well as how dangerous they can be.

9. Meng Po

Also known as Aunt or Granny Meng, this deity of forgetfulness is depicted as an old woman in Chinese culture. She is a key figure in the mythology of the Chinese underworld, called Diyu. The people who follow this folklore believe that upon death, everyone passes through Diyu where you are punished for the sins you committed in this lifetime in different courts dedicated to specific punishments—such as being crushed or getting bitten by snakes repeatedly for years—before entering the tenth court to be reincarnated.

In most versions of the story Meng Po is waiting either in the ninth or tenth court with her Meng Po soup which she offers out to people. The souls drink the soup so they forget their memories and can start again when they reincarnate but occasionally people do not drink the soup which results in children remembering their past lives.

Meng Po is thought to have originated in China in the 1st century CE, but many historians think she could be much older. In this first story, she was once a mortal woman whose husband died building the Great Wall of China, and her grief was so great that she could not reincarnate. Therefore, she created the Meng Po soup so no one else would suffer as she did. In a story from the 11th century CE, she was originally a Buddhist who became so engrossed in scripture that she got lost between the past and the future.

Usually, Meng Po is seen as a benevolent figure, helping people forget how they were tortured in Diyu and also while alive on Earth. She is comforting to those who are close to the unfathomable and unavoidable experience of death and a reminder that our existence is cyclical and nothing, especially pain, lasts forever.

10. Aida

According to folklore from Senegal, a girl called Aida was born after her mother escaped a brutal regime in which the king of Tarokoro had baby girls and their mothers killed as he only wanted boys. Aida grows up away from the regime and realizes that she can control the rain with her prayers and she subsequently prays the rains will fall everywhere but on Tarokoro.

After severe droughts and crop failures, a spy tells the king of Tarokoro that Aida is somehow controlling the rains and he sends for the teenage girl. The king asks Aida why she would do this to his kingdom and she in turn scolds him for his transparent sexism and instead asks him why he would kill baby girls at birth.

It is then revealed to Aida and the audience that the king views men as productive and useful but women as the opposite. Undeterred, Aida contends she can do anything a boy can do and had to learn everything herself to stay alive, so the king agrees to end the policy.

Around the world, women have been connected to water in many folktales and mythologies, primarily due to their abilities to give life. A woman controlling and withholding water from men is a very literal way of demonstrating a woman’s power in the world and there is an overt irony when the king sees women as unproductive despite women’s role in the process of reproduction. Furthermore, the Senegalese climate can be extreme, and the country is known to experience highly variable weather which makes the story of Aida even more significant.

Aida is bold and brave in her approach to the king regardless of her being a teenage girl. Thus, Aida is frequently seen as a feminist icon as her feminine anger, unlike in many traditional stories, is seen as justified. Her courage and unrelenting approach to justice often appear as an inspiration to many women.