Richard Nixon’s presidency is a study in contrasts. He achieved significant foreign policy successes and domestic environmental and social progress, yet Watergate ultimately tarnished his legacy, overshadowing all that came before it. The thirty-seventh American commander-in-chief is remembered as both a consequential president and one who brought down his own administration and legacy.

Appealing to the Silent Majority

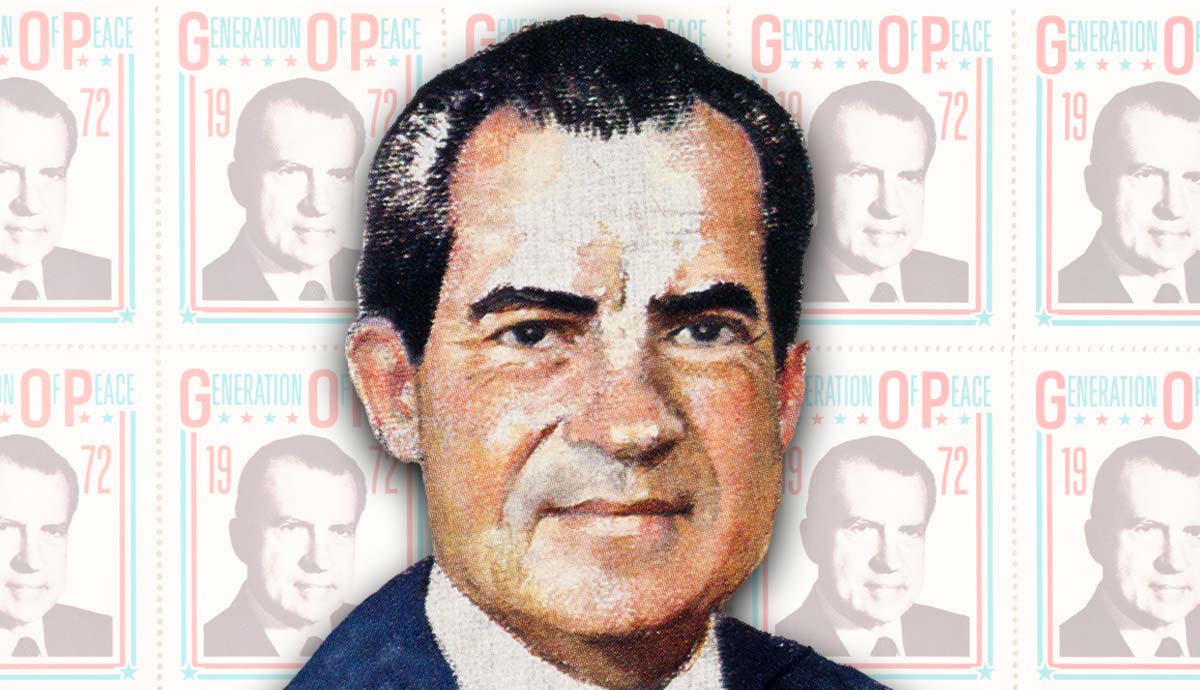

The year 1968 would go down in history as one of chaos and violence. With the disastrous Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, civil rights unrest, political polarization, and violence at the Democratic Convention stemming from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s refusal to continue as the American president, the Republican party had finally caught a break. After nearly a decade of having Democrats residing in the Oval Office, former vice-president Richard M. Nixon’s promise of unifying the nation, restoring law and order, and ending the Vietnam War was enough to propel the one-time 1960 election loser to the White House.

Having won the office by appealing to what he labeled as “the silent majority,” or those whose support for the government that the anti-war and civil rights protesters suppressed, Richard Nixon set off to baffle both the liberals who hated him and the conservatives who put him into office. The new president’s “Southern Strategy” of appealing to his strong voter base below the Mason-Dixon line was in line with his party’s stance on segregation.

To keep the promises he made to the influential South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond for the promise of his backing in the general election, Nixon now opposed court-ordered busing as a step to slow down desegregation in the South and cut off federal funds for racially segregated schools, and named a Southerner to the Supreme Court. The new executive also targeted antiwar protesters by enforcing laws against draft evaders and radical student protests.

But then, to the surprise of many, the strict conservative leader began pushing through measures to help the needy, elderly, and handicapped, all while recording a record number of environmental legislation and shifting power away from the federal government and back to the states and local communities.

Welfare and the Nixon Administration

After failing to pass his initial Family Assistance Plan aimed at fixing the “welfare mess” left over from his predecessor’s Great Society Program, President Nixon set off to, as historian W.J. Rorabaugh said, “beat the liberals at their own game,” with proposals that would typically fit right in on the left side of the aisle instead of with his conservative base.

The initial proposal from the White House was to provide each family a guaranteed yearly federal assistance of $1,600, which encouraged citizens to continue seeking work to supplement the grant, not having to worry about necessities. After white conservatives disapproved of the proposal’s guaranteed income, which many House Republicans believed would be too expensive and mainly benefit disadvantaged Black families, who made up a significant portion of welfare recipients. The liberal contingent attacked the plan because it did not provide enough money for a comfortable life.

Nixon withdrew the proposal and instead introduced a new comprehensive food stamp program that had been dormant since the Great Depression. By the end of his presidency, food stamp recipients grew from 3 million to 15 million. In 1972, the president followed the program by signing the Supplemental Security Income Act (SSI). Apart from increasing Social Security benefits, extending subsidized housing, and expanding the Job Corps program, the SSI provided financial assistance to the elderly, people who are blind, and people with disabilities.

To reduce the size and influence of the federal government, President Nixon pushed through Congress a series of revenue-sharing bills granting federal funds to states and allowing them to spend it as they pleased. While providing more freedom to local governments on paper, the program made states more dependent on federal funds and its imposed conditions for releasing them.

Nixon and the Environment

At the time of his presidency, Richard Nixon’s critics accused the Republican president of overreaching and abusing executive power. Yet, in many cases, the same detractors gave him credit for using that same power to extend the federal government’s role in protecting the environment. As Congress appointed money for democratic-led programs, Nixon often opposed them by impounding or refusing to release the needed funds—a total of $15 billion by 1973.

When it came to the environment, the Republican leader was more willing to focus on bipartisanship, working with both Democrats and Republicans to achieve legislative success. Initially spearheaded by Congressional Democrats in 1969, following an oil well that burst off the California coastline and covered the beaches near Santa Barbara with sludge, Nixon took the lead in establishing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The president’s environmental policy record included landmark legislation and laid the groundwork for lasting ecological protections. While the EPA consolidated environmental enforcement and research by bringing criminal actions against polluters, the President also pushed through Congress the Clean Air Act, Endangered Species Act, Marine Mammal Protection Act, and a Legacy Parks Program that established new parks from surplus federal lands. By the time he stepped down as the president of the United States, Richard Nixon had passed more environmental legislation than any commander-in-chief before him.

Vietnamization

Nixon’s administration was pragmatic and strategic in garnering public opinion on its record of dealing with and responding to the nation’s significant issues. When the Supreme Court issued the monumental decision, Roe v. Wade, in 1973, that established the constitutional right to abortion in the United States, Nixon, even after pressure from his constituents, refused to make any public statements on the issue. Many of his critics pointed to this fact as just another way, like his environmentalism, the president attempted to appear progressive and distract the public from the Vietnam War.

Richard Nixon’s role in the Vietnam War is complex and controversial. While he promised to end the war “with honor” during his 1968 campaign, the president initially intensified the war effort by increasing bombing campaigns in North Vietnam and expanding the ground war into the neutral country Cambodia.

As universities around the nation exploded in more anti-war protests, including the deadly shooting of protesters by National Guardsmen at Kent State in 1970, Nixon began his policy of Vietnamization. Some pointed to the fact that Nixon’s administration stifled early peace talks between the US and North Vietnam when he was still president-elect so he could get the credit for taking the country out of the war, only to pass a program that would take years and drag the war out at the cost of thousands of American lives.

While historians still debate the effectiveness of Vietnamization to this day, there is no denying that it did effectively end the US armed conflict in Southeast Asia. As part of the program, the United States military trained and equipped the South Vietnamese forces to take over the fighting as American forces gradually withdrew from the peninsula. After years of negotiations, President Nixon finally signed the Paris Peace Accords in 1973, which ended the US military involvement in Vietnam and established a ceasefire.

In retrospect, Nixon never achieved his “peace with honor.” The nation’s military involvement in its most controversial war was over, yet South Vietnam fell to a renewed North Vietnamese major offensive in 1975, uniting the country under communist rule.

China and Détente

Richard Nixon’s overall time in office—excluding its shameful conclusion—is today often judged not so much by its domestic dichotomy but by its successes on the global stage. By the 1960s, relations between China and the Soviet Union had deteriorated along ideological lines, territorial disagreements, and competition for leadership in the communist world. President Nixon and his national security adviser, the former Harvard professor Henry Kissinger, saw the Sino-Soviet split as an opportunity to exploit the growing tensions between the two major communist powers.

The Nixon administration’s process of relaxing Cold War tensions, known as Détente, began with the effort to improve relations with China, whose vast population and economic potential seemed ideal for bolstering trade and economic opportunities for the United States. A closer relationship with communist China, which the United States, up to that point, refused to recognize while officially backing democratic Taiwan, was seen as a step toward weakening the Soviet Union’s global influence. Nixon lifted trade and travel restrictions, withdrew the Seventh Fleet from defending Taiwan, and embarked on a historic trip that saw an American president visit China for the first time in history.

The strategy of having the US, China, and the Soviet Union all wary of one another’s power worked, as the latter responded to the budding American-Sino relations by initiating their own rapprochement with the United States. The historic Moscow summit in May 1972 led to the signing of the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT), limiting both nations’ nuclear armament. A Soviet official at the time of Nixon’s presidency stated, “The United States and the Soviet Union had their best relationship of the whole Cold War presidency.” Yet, despite his foreign triumphs, trouble was brewing for Richard Nixon back home.

Watergate and the End of the Road

President Nixon’s reelection win and subsequent loss of the American presidency began in the leadup to the 1972 election, which the Republicans were already projected to win in a landslide. In June of that year, police arrested five burglars attempting to break into and install bugging equipment at the Democratic National Committee headquarters located in the Watergate complex in the nation’s capital. Found to be connected to the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP, more commonly known as CREEP) working on Nixon’s reelection campaign, the individuals’ arrests directed unwanted attention at the Nixon administration.

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, two young reporters from the Washington Post, turned the news into an international incident with the help of an anonymous source within the Nixon administration that hinted at a conspiracy involving those closest to the president. As their reporting exposed a cover-up orchestrated from within the White House, public pressure mounted, forcing Congressional hearings and further investigation into the scandal. Before long, Nixon’s illegal obstruction of justice would overshadow the crime as recordings made in the Oval Office—initially withheld from Congress by the president—revealed Nixon’s knowledge and participation in the cover-up attempts of the connection between CREEP and the Watergate break-in.

The Watergate scandal, which became a defining moment in American political history by exposing the dangers of unchecked presidential power, led to Richard Nixon’s resignation, the only president to do so, on August 9, 1974. Following his pardon at the hands of his successor, Gerald Ford, Nixon, facing public disgrace, retreated from public life.

A Complicated Legacy

Decades since the term “Watergate” has become synonymous with Nixon, political scandal, and corruption, and thirty years since the former president’s death, the shadow of the scandal continues to loom over Richard Nixon’s legacy. Was he a good president or a crook?

Perhaps in 2024, decades after Watergate and administrations littered with more political scandals, divisive politics, and contentious presidencies, enough time has passed to reevaluate the complicated legacy of American President Richard Nixon. If one looks under the looming shadow of the Watergate scandal, the thirty-seventh president achieved significant foreign policy successes, albeit at a terrible human cost, during the Vietnam War. Nixon’s domestic policies also remain a mixed bag, and his image is not helped any by ruthless political acumen and tendency to play above the law when it came to his opponents, which earned him the nickname “Tricky Dick.”

Richard Nixon leaves behind a complex web of achievements and failures, successes and scandals—a brilliant strategist with serious ethical lapses.