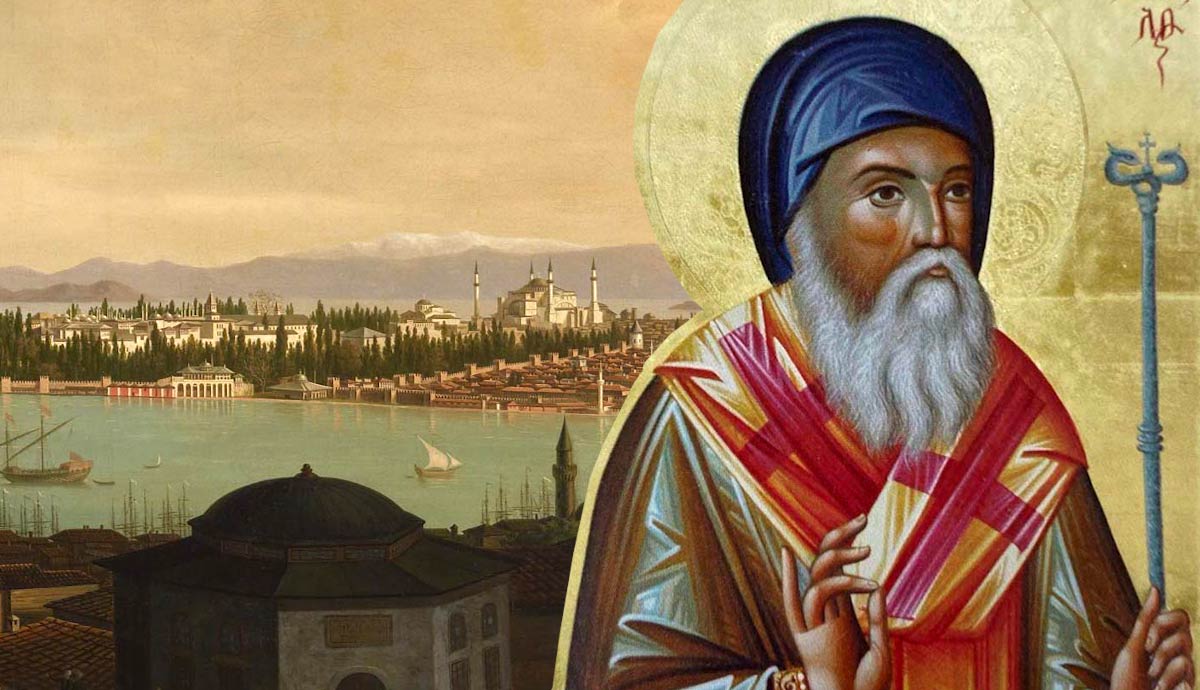

These words were written in the Eastern Confession of the Christian Faith of 1629, signed, by Orthodox Patriarch Cyril Lucaris: “The righteousness of Christ, being applied to the penitent, alone justifies and saves the faithful.” The confession does not call itself Protestant — but the language therein seems explicitly so.

How could this statement have been signed under the name of the Patriarch of Constantinople, the most honorable office in the Eastern Orthodox Church? Some Orthodox Christians have historically denied Lucaris’ authorship, suggesting that the signature was a scheme concocted by his Jesuit opponents. Who was Cyril Lucaris, and how did he become associated with the Protestant movement?

Who Was Cyril Lucaris?

Cyril Lucaris (1572-1638) was the Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church in Alexandria (from 1601-1620) and then Constantinople (1620-1638). He is one of the most controversial—though historically obscure—figures in the story of the Reformation in Eastern Europe. He had many enemies, so much so that his patriarchate would resemble the Church Father Athanasius’ career; he was exiled and reinstated no less than six times before his death. His life met a brutal end as he was accused of treason against the Ottoman Empire and was killed by Ottoman authorities during his patriarchate in Constantinople.

The full scope of the controversies and complexities of the life of Cyril Lucaris are beyond the scope of this article. For our purposes, we will benefit most from studying Lucaris in light of the Eastern European Reformation, as an Orthodox bishop living in a tug-of-war between Protestant and Catholic communities in Poland; this experience affected his mindset later in life.

Lucaris’ ministry in Poland was the most formative period of his life and it developed his theological framework and set the tone for his interactions with Protestants. Eastern Europe—primarily Poland—is the fundamental place of interest for understanding this patriarch.

Cyril’s Early Life

In 1572, Cyril (then Constantine) Lucaris was born on the island of Crete. He was known to be a precocious young child, and he began to study in Venice with Bishop Maximos Margunios at twelve years old. Several years later, Lucaris continued his education at the University of Padua and studied philosophy there. He remained in frequent contact with his old teacher, and we possess letters passed between them, ranging from philosophical discussions to Margunios’ reprimand of Lucaris for his sloppy handwriting.

Lucaris would study at Padua for six years, and it is probable that this period (according to Stephanie Falkowski’s work on Lucaris) was his first exposure to Protestant thought, for the university was home to many Protestant students from Western Europe. The Catholic Church in Padua was nowhere near as influential as it was in virtually every other region of Italy; there were even occasions when Jesuits were banned from teaching religious matters at the school. Thus, it is a safe assumption that at Padua Lucaris received a comprehensive education in philosophy, an exposure to Protestants and their ideas, and perhaps even a new antagonism toward the church of Rome. Lucaris would be ordained into the Orthodox priesthood soon after graduating at Padua and henceforth would be known as Cyril Lucaris.

Cyril Allies With Eastern Protestants to Preserve Orthodoxy’s Independence

The newly-ordained Cyril lived for a time with an Orthodox community in Padua but was soon ordained into the bishopric. He was sent to serve a small Orthodox parish at Brest-Litovsk in the Kingdom of Poland. While there, he attended the second session of the Council of Brest, an episode in Polish church history in which several Orthodox bishops voted to unify with the Roman Catholic Church (in a religious and political movement known as “unia”). Lucaris adamantly opposed this union and sought to protect the independence of his Orthodox churches, and thus looked to the Polish Protestants for an ecumenical effort against the Catholic domination of Poland.

Lucaris corresponded with numerous Calvinist communities in the cities of Lublin and Vilna. There was even a Protestant faction at the second session of Brest which sided with Orthodox Christians against unifying with Rome, led by Prince Constantine Ostrogski, an Orthodox prince and avid supporter of Protestantism. Ostrogski placed Lucaris under his provision. Thus, it is clear that by this time Lucaris viewed Protestant communities as being his allies against the church of Rome.

Cyril’s Protestant Ideas Brought Education to Orthodox Laypeople

Many Reformation scholars have noted that the Protestant Reformation democratized education for all laypeople, and Cyril Lucaris perfectly embodied this movement. Cyril’s collaboration with Prince Ostrogski also included a successful effort to create Orthodox schools and set up printing houses in Poland. Thus, it is clear that by this time Lucaris viewed at least some Protestant communities as allies in his efforts to reinvigorate and educate a suppressed Orthodox people and compete with Jesuit influence.

In 1601, Lucaris was granted the opportunity to bring these reforms to a global stage as he received a letter which virtually promised him succession of the Patriarchate of Alexandria, and he gladly accepted. As Patriarch, Lucaris immediately reorganized the church’s finances and started an initiative to reform schooling in Alexandria. Steven Runicman in his monograph The Great Church in Captivity notes that Lucaris’ interactions with western religious thought in Padua and Poland no doubt influenced his ambition for major reforms in his own church.

Among Cyril’s greatest reformation achievements, though, came following his appointment as the Patriarch of Constantinople. Lucaris made his last trip to Constantinople as a visitor in 1620, when the Patriarch of Constantinople died. The people of the city saw Lucaris as the clear choice for a successor. The Orthodox community there lauded Lucaris for his strong faith and his reforms in Alexandria and hoped he would do the same for Constantinople. Lucaris sought to fulfill their expectations and more, but his full initiative to reform the church in Constantinople did not go as planned, as he was deposed and reinstated six times during this period due to difficulties with the Jesuits and the Ottoman authorities.

Lucaris sought to serve the educational needs of his community by establishing the Academy of Constantinople in 1627. This academy sought to give religious education to Orthodox Christians as well as to educate people in the natural sciences. The Academy was also fitted with the first printing press in the Greek world, staffed by a Protestant printer from London. At this press, Lucaris famously published the first New Testament in his contemporary Greek so that, as Lucaris said, “the faithful would be able to read the Bible alone and by themselves.” Thus, Lucaris’ Protestant-minded initiative in Constantinople was to put the Bible in the hands of all the laity and to provide a robust education system that would be a viable Orthodox alternative to the Jesuit schools.

Cyril’s Protestantism Reintroduced Patristic Studies to Western Europe

Meanwhile, Lucaris in his private life continued to immerse himself in Protestant literature as he received books from the English ambassador Thomas Roe, who referred to Lucaris as a “pure Calvinist.” He communicated with Roe frequently and would often receive Protestant books from him for his reading pleasure. Most notably, it was through Roe that Lucaris sent the Codex Alexandrinus to King James I. The codex was an early 5th century manuscript of the Greek Bible which contained the Old Testament, the Deuterocanonical books, the New Testament, and 1 and 2 Clement.

While 1 and 2 Clement were known and appreciated in the early church (primarily in Corinth and in the letters of Clement of Alexandria), they did not circulate very widely in the Middle Ages. Thus, the original texts of 1 and 2 Clement were virtually unknown in Europe prior to Lucaris’ gift of the Codex. Several years after the codex arrived in England, the patristics scholar Patrick Young worked from the codex to publish his first editions in 1633. Those studying the letters of 1 and 2 Clement today hold Lucaris in their debt.