His words offered a different reality to millions of people, and his fame blossomed across the nation. Ralph Waldo Emerson became a beloved figure for a people struggling to find a purpose, not just for themselves but for a fledgling country grappling with the dynamics of independence. Emerson inspired a new way of thinking, introducing Americans to an existence of appreciation and enlightenment through individual communion with the divine. His words and his actions are as relevant today as they were over a century and a half ago.

The Early Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson

Born on May 25, 1803 in Boston Massachusetts to Ruth Haskins and the Reverend William Emerson, Ralph Waldo Emerson was one of eight children, though only five survived to adulthood. His father was one of Boston’s leading figures and as a Unitarian minister, a person with much influence in local society.

Through his mother, Ruth, Ralph was a direct descendant of John Howland and Elizabeth Tilley who traveled to America aboard the Mayflower. Ralph represented the seventh generation of Americans descended from these colonists.

Before Ralph could even speak, his life’s work had been determined for him. It was decided that he would follow in his father’s footsteps and join the ministry.

On May 12, 1811, just before Ralph’s eighth birthday, his father died of stomach cancer, and as a result, Ralph spent the rest of his childhood and young adult life in a fairly matriarchal setting, raised by his mother as well as his aunt, Mary Moody Emerson.

Emerson’s schooling was not particularly unique. It began at the Boston Latin School and then progressed to Harvard College. During his first year at Harvard, Ralph started keeping a journal of his thoughts—a practice he would continue for the rest of his life.

At school he became known for his poetry but was an average student, achieving grades in the middle of his class of 59 students. After his studies, he became a teacher and taught at the School for Young Ladies. During this time he spent two years living in a cabin near Roxbury, Massachusetts. His lifelong passion for the outdoors would come to define his philosophy on life.

In 1825, he entered Harvard Divinity School and began his training to become a minister. The following year, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, a disease that would haunt him throughout his life. He moved south to Charleston, South Carolina, then on to St. Augustine in Florida, where the warmer climate was far more conducive to recovery.

During his time in the South, he met Prince Achille Murat, a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. The two enjoyed each other’s company and became good friends. The juxtaposition of their differing worldviews was, however, a factor that shaped the future philosophy of Emerson. While Emerson was training to become a minister, Murat was an atheist who lived a life of passion, indulging in the fruits that life had to offer.

It was also in the South that Emerson had his first real brush with something that would significantly define his philosophy later in life—slavery. One morning while sitting in church listening to the pastor’s sermon, his ears were assailed by the noise entering the church from an open window. It was the sound of a slave market next door. Emerson began struggling to reconcile how the two could exist in such close proximity, and he started internally questioning the Christian doctrine.

Marriage and Tragedy

Emerson met Ellen Louisa Tucker on Christmas Day, 1827. She was 16 at the time, and he was 24. They fell in love, marrying two years later.

Emerson wrote in his diary, “Oh, Ellen, I do dearly love you. I have now been four days engaged to Ellen Louisa Tucker. Will my Father in Heaven regard us with kindness, and as he hath, as we trust, made us for each other, will he be pleased to strengthen and purify and prosper and eternize our affection.”

They moved to Boston and lived with Emerson’s mother, Ruth. By this time, however, Ellen was already showing symptoms of tuberculosis, and at the age of 20, she succumbed to the disease.

Emerson, naturally, was distraught. The love of his life was gone, pushing him to further question his religious beliefs. His prayers had been answered with an unmerciful hand.

Emerson visited his late wife’s grave five miles away from his house on a daily basis. On one occasion he did something startlingly odd, while noting simply in his diary, “I visited Ellen’s tomb & opened the coffin.” Why he did this is subject to academic and philosophical debate. It is usually stated that it was not so uncommon in a time period when people had a more intimate relationship with death.

In 1832, Emerson left the ministry. He believed the methods of commemorating Christ were outdated and antiquated, and he could not accept that unity with God had to come from an outside source.

Seeking answers to life’s questions, he left the shores of America and sailed to Europe. He traveled throughout much of Western Europe and met with several of the continent’s greatest philosophers and thinkers. In Rome, he met with John Stuart Mill. In Switzerland he visited the home of Voltaire, and in France he explored the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. It was at these gardens that he stumbled upon the revelation that everything in the natural world was interconnected, and it was this idea that informed the philosophies he would so ardently expound upon returning to America.

While in Britain, he met with William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas Carlyle. He formed a good relationship with Carlyle, who inspired Emerson to follow through on the thoughts he had while in the Jardin des Plantes. The two men wrote to each other regularly until Carlyle’s death in 1881.

Emerson Returns to America and Creates a Philosophy

After his return to America, Emerson took much interest in the Lyceum Movement, a loose collection of adult education programs. Through this movement, Emerson envisioned himself becoming a lecturer. On November 5, 1833, he gave his debut lecture about his experiences and revelations in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. This lecture would go on to form the foundation of his first book, simply entitled Nature. Virtually everything he wrote and published later would be connected to this seminal work.

Happy times followed and he fell in love again. On January 24, 1835, he proposed to Lydia Jackson via mail. Her acceptance reached him four days later. In July of that year, he bought a house in Concord, Massachusetts which he named Bush, and in September, he traveled to Plymouth to marry Lydia. After they were wed, they lived together with Emerson’s mother in his house in Concord. For the rest of their lives, Emerson would refer to his wife as Lidian as he wanted her to have a less common name, though he most often called her “Queenie.”

In 1836, he met with other like-minded individuals and formulated the basis of the philosophy that would characterize his work—Transcendentalism. This movement was philosophical, spiritual, and literary, and at its core was the belief in the inherent goodness of people and nature. It saw beauty in the mundane and believed in achieving unity with God through appreciating the wonder of nature on Earth, rather than focusing on something far away that could not be experienced through the senses.

During this time Emerson met Henry David Thoreau, and the two formed a strong friendship. Thoreau was enthusiastic about the Transcendentalism movement, and the two went on regular hikes through nature, bouncing philosophical ideas off each other. The subsequent works of both men were influenced by and bore the hallmarks of the other’s way of thinking.

Naturally, his work was not without its detractors. In 1838, he gave a speech challenging the notion of salvation through Jesus. He was lambasted with harsh criticism from the public who were staunchly Protestant. Nevertheless, he made no attempt to reply or defend himself, and his work continued to gain popularity. In 1841, he published his second book, Essays.

Ralph and Lidian had four children together—Waldo, Ellen, Edith, and Edward. In 1842, tragedy struck, and Waldo, only five at the time, died of scarlet fever. Unsurprisingly, Emerson struggled to come to terms with the loss of Waldo, a child who held a central place in Emerson’s life.

Emerson’s career, however, went on. He continued publishing and giving lectures. His lectures were immensely popular, and he went on tour, giving as many as 80 lectures per year. During this time, he also influenced the work of fellow transcendentalist Margaret Fuller who developed a dangerous affection for Emerson. The relationship, however, didn’t develop into anything physical.

Emerson and Abolition of Slavery

Emerson had long been an opponent of slavery, but the realities of it were far removed from his life in New England, where he rarely encountered a Black person, let alone one treated as slaves were in the South. Emerson was also wary of getting into politics and attracting attention in the abolitionist context. He viewed many outspoken abolitionists as more concerned with extolling their own virtues than in helping enslaved people.

Encouraged by his friends and his wife, Emerson slowly warmed to the idea of giving speeches on the matter. By this time, he had become one of the most famous men in America, and his voice had the power to influence millions of people.

In 1860, Emerson published his seventh collection of essays, The Conduct of Life. In it he addressed issues of slavery and abolition, stating that going to war over the issue was preferable to peace with slavery.

Such was his influence that he met with Abraham Lincoln and a number of other high-ranking government officials.

Emerson’s Final Years

Despite having a falling out with Henry Thoreau in 1849, Emerson still regarded him as his best friend, and when Thoreau died from tuberculosis in 1862, Emerson delivered the eulogy. Two years later, another prominent friend of his died—Nathanial Hawthorne. Emerson served as a pallbearer at his funeral.

Beginning in 1867, Emerson started losing control of his mental faculties. He suffered from aphasia, a particularly sad condition for one whose life revolved around words. He nevertheless continued to live life to the fullest. In 1871, he took a long journey on the transcontinental railroad, during which he met Brigham Young and the famous mountaineer, explorer, and conservationist John Muir.

In 1872, his house burned down. Emerson decided that this incident was the point at which he should retire, and he gave up public lectures, although he still gave talks to very small groups of people. Later that year he took a trip with his daughter, Ellen, to Europe and Egypt.

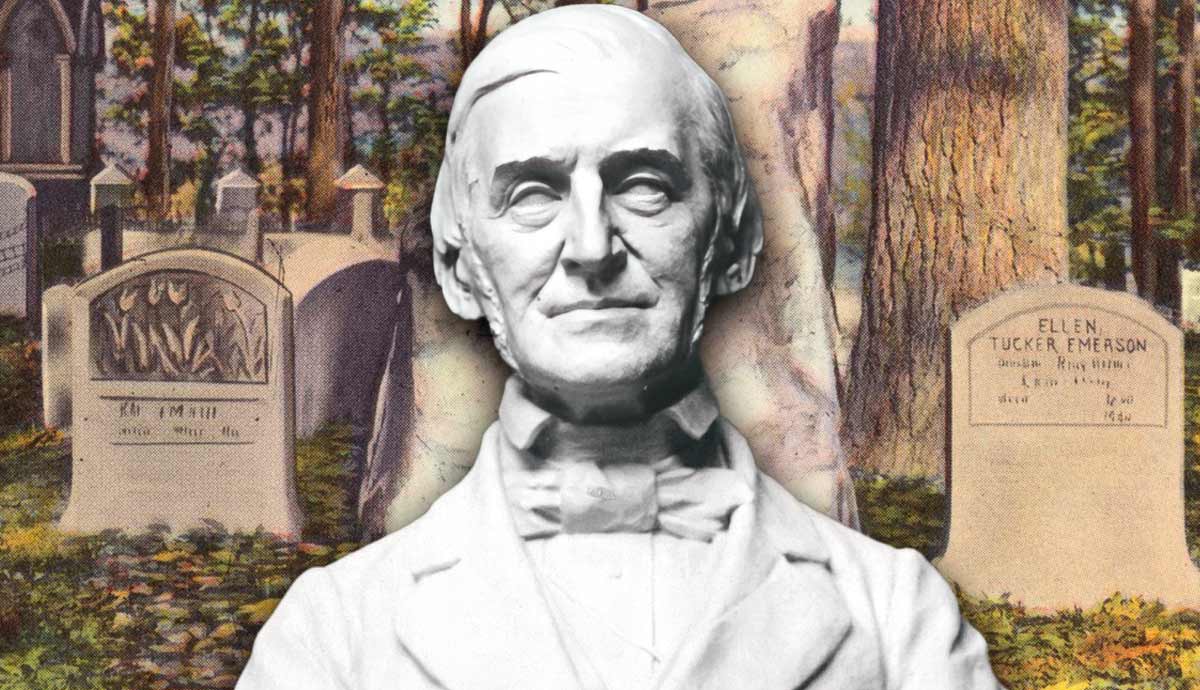

As the decade progressed, his aphasia worsened, and he became more reclusive as a result of his embarrassment over his condition. On April 27, 1882, he died of pneumonia. He was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts.

Legacy and Conclusion

Ralph Waldo Emerson was a giant in the field of philosophy. The 1,500 lectures he delivered over his lifetime took him to the heights of fame in his age. He constructed and advanced many of the tenets on which America was built. He championed individualism, but also humanity, and had an irrepressible sense of justice.

The importance of Ralph Waldo Emerson and the impact of his work cannot be overstated.

He created the Transcendentalist movement with its five pillars: nonconformity, free thought, self-reliance, confidence, and importance of nature. These pillars are still evident in the psyche of the American people today, and form a natural and national framework around which America progressed and still progresses.