What could be more exciting than discovering a lost city? Across the world, ears perk up at the mere mention of a lost city that has been rediscovered because we are all romantics and curious at heart! We were brought up with fairy tales and buried treasure.

How on earth can a city be lost, and what exactly qualifies as a lost city that can be “rediscovered”? Who lived there? How did it end? Why was it, or knowledge of its location, “lost”? Unless you are a student of history, an archaeologist, anthropologist, adventurer, or explorer, chances are that you have not really considered these questions, and yet you may be intrigued enough to read on.

Tell Mardikh in Syria: The Ancient Lost City of Ebla

Discovered by chance, like so many ancient sites, ancient Ebla was a thriving metropolis as far back as 5000 BP. Until the 1960s the areas outside of Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Egypt had been viewed as backwaters or welcome stops on major trade routes between these three major areas of civilization. Luckily, an Italian archaeologist, Paolo Matthiae, decided that some of the mounds might be worth investigating.

He started excavating the largest mound, Tel Mardikh in 1964, and by 1974 they had discovered a number of cuneiform tablets in a Semitic dialect. The tablets appeared to be from a larger source. The story goes that Matthiae’s wife was visiting her husband at the site later. As she casually leaned against a wall, it gave way, and low and behold, the first and oldest cuneiform library dating to circa 2350 BCE was discovered on collapsed shelves.

Archaeologists found that the tablets had been “filed” by subject, when they were fitted back into their places! A wealth of information about Ebla and the entire Middle East was revealed when scholars deciphered the texts.

The city had close ties with Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the rest of the Mediterranean world. The languages of the texts were Sumerian and an unknown Semitic dialect, later named Eblaite. Lexicons of Sumerian, Akkadian, and Eblaite helped with translations and decipherment of texts from across the ANE.

It was indeed the long-lost city of Ebla mentioned in texts from outside sources, which flourished between the 3rd Millennium BCE and 1600 BCE. It was destroyed and resettled twice, then the Hittites finally destroyed the city in 1600 BCE, and it was not resettled again. The city’s location became a lost legend, and the ruins were just another nameless mound until archaeologist Paolo Matthiae took a chance on Tel Mardikh.

Access to the site is not possible since 2011 when the terror conflict started. Drone footage from 2020 indicates large-scale looting and destruction, but ground access is impossible due to potential landmines.

The Lost City of Troy: No Legend After All

We all know about Troy, right? The city that Hollywood made films about. The city Helen of Troy was abducted to by Paris, Prince of Troy. The brave, besieged city was outplayed by Odysseus’ clever plan, the famous wooden horse filled with soldiers. The city was made famous by Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey which bordered on fantasy, so it had to have been a legend only. Or so the world thought!

In the 18th and 19th centuries interest had already returned to the Classics. Debates about fact or fiction were rife because many ancient authors like Homer mixed facts with fiction. In 1801 Edward Clarke identified a low hill at Hissarlik in Turkey as ancient Troy because of coins and inscriptions he found on the surface. In 1868 a local landowner convinced Heinrich Schliemann, a retired ex-banker from Germany with a dogeared copy of Homer’s Iliad always with him, to dig on Hissarlik.

In the layer today identified as Troy II, Schliemann struck gold — literally and figuratively. He bedecked and photographed his young Greek wife with the magnificent jewelry and announced to the world that he had found Homer’s Troy, and King Priam’s treasures. Today we know that this layer was about 1000 years older than Homer’s Troy.

The original city was founded around 3000BCE. It existed for around 4000 years. Scholars have identified settlement layers one on top of the other, and they have named them using Roman numerals. Various layers experienced destruction by fire, earthquakes, and battles.

The choice of location at the entrance to the Dardanelles/Hellespont contributed greatly to the wealth of the city through tolls and trade. Homer’s Troy is tentatively identified with its Late Bronze Age heyday in layers Troy VI and Troy VIIa. War hero Hector was involved with horse breeding and there is evidence of this, wool textiles, and trade, present in these layers.

Since the lost city of Troy was rediscovered, we have to accept that Homer’s legendary tale was after all based on real history.

Mari: Maybe the First Planned City

Mari was perhaps the first city that was planned, from its selected location to its outlay. The first outlay was circular, with a defensive wall to stop floods and enemy armies. The site has three cities, one on top of the other. It flourished from 2900 BCE (some say 3100 BCE) to its final destruction by Hammurabi of Babylonia ca 1760 BCE. Small settlements thereafter lasted until ca 600 CE, after which Mari disappeared from history and memory.

It sat at an ideal spot on the west bank of the Euphrates River, serving as a hub between the various cities and states of the Bronze Age. Raw materials from the Taurus Mountains included copper and tin needed for making bronze. Smelting plants for bronze and other metal works were uncovered during excavations at Mari Tel al Hariri. Rich farming land was utilized for agriculture and domesticated animals were used to supply the trade caravans and river traffic.

The city controlled two large canals. One canal supplied the city and agricultural developments with water. It ran through the city. The second canal was 120 km (almost 75 miles) long, and used for shipping with toll sluices that enabled boats to bypass the rapids and bends of the Euphrates.

Discovered by Bedouin digging graves in the 1930s, it was excavated by archaeologists since 1933. The third city of Mari’s kings is included in the Sumerian Kings List from 2084 BCE. The new palace of the last king, Zimri-Lim (1779 to 1757 BCE), boasts 300 plus rooms, passages, and courtyards. 25,000 clay tablets in Akkadian for the period 1796 – 1757 BCE were found from this phase. These kings were Semitic Amorites. The city was, however, cosmopolitan in culture through trade associations.

Much of the city was washed away by the Euphrates after Hammurabi had it burned down, with only about one-third remaining. The jewel in the crown for scholars was the discovery in 1998 of a small isolated and crumbling building containing around 2000 clay tablets. Dare we say it? This appears to be an ancient school room! The tablets are a treasure trove. Lexical lists, mathematical exercises, proverbs, literature, letters, contracts, and a list of Semitic names confirm Sumerian and Akkadian presence at Mari.

According to Unesco’s World Heritage List, Mari is the best-understood city from antiquity in the ancient Near East after forty-two excavations. Drone footage from 2020 indicates extensive damage and looting since the terrorist conflicts started in 2011, and the site remains inaccessible due to landmines.

Akrotiri: Legacy of a Volcano

There are so many legends and stories connected to the massive eruption of the Thera volcano ca 1650 BCE. Even the dates vary between 1650 – 1550 BCE to suit different scenarios. What we do know is that a once-thriving trade connection between Cyprus, Crete, mainland Greece, the Levant, and many other places was destroyed. Ashes have been found as far away as Egypt, and other Mediterranean countries. The center of the island sank beneath the waves. Tsunamis and earthquakes devastated other islands and Minoan cities and settlements in Crete. What was left of Thera was newly settled in the 8th century BCE by the Dorians and it was later a naval base for the Ptolemies during the Hellenistic era.

The ancient lost city of Akrotiri was rediscovered in the 1860s by quarry workers, but only re-entered history in 1967. Renowned Greek archaeologist, Spiridon Marinatos, was researching a theory that the destruction of the Minoan civilization on Crete started with the eruption of Thera. Because there are no records of this city, it was named Akrotiri by modern scholars, after the small village nearby.

Akrotiri on the island of Santorini in the Aegean Ocean was remarkably sophisticated. The houses had inside plumbing, toilets, and plastered walls with magnificent frescoes preserved under thick layers of volcanic ash. Some were three stories high. There are no palaces, and curiously no human remains or personal treasures. Scholars are convinced that Thera gave ample warning before it erupted, allowing for a timely evacuation of people and livestock. Unless, of course, some were washed away into the depths of the ocean, their vessels overcome by giant tsunamis…

This lost city is reckoned as part of the advanced Minoan civilization from Crete — a halfway station on their trade routes. Maybe once Minoan Linear A script is finally deciphered, we will know more about this fascinating lost city of which only a portion has been excavated.

Mohenjo Daro: Lost Cities of the Indus Valley

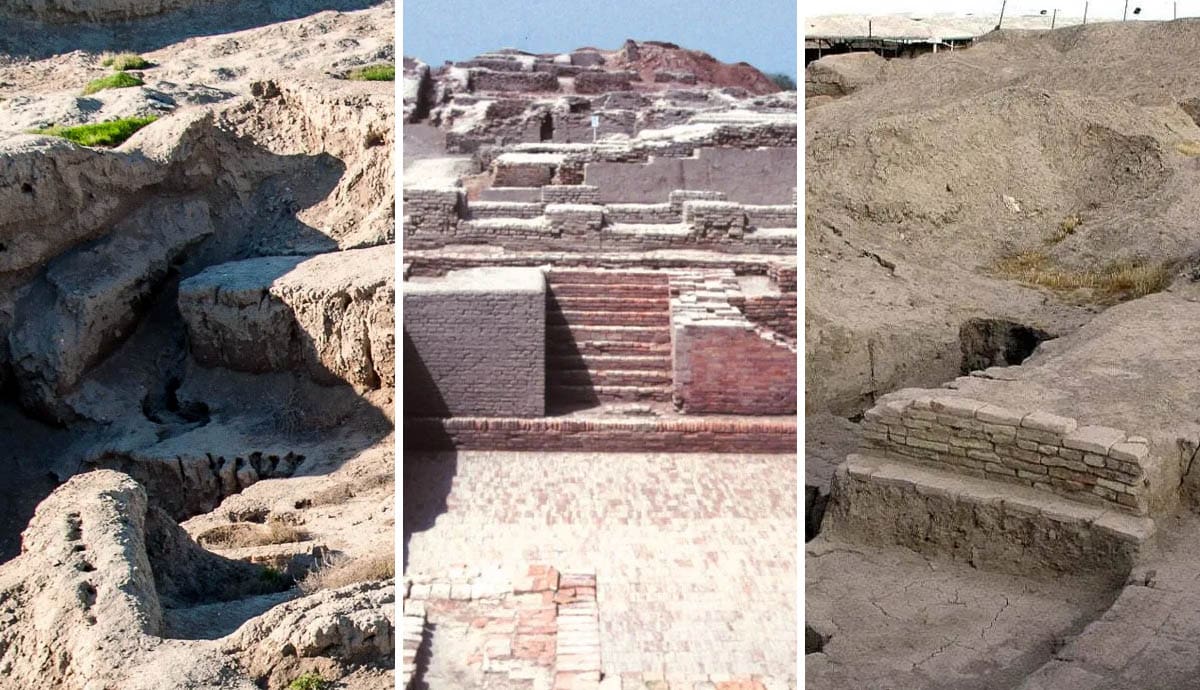

Before the pyramids, and before the first dynasties of Egypt, at the time of Sumer and Akkad, there another civilization peaked for a thousand years between 2500 BCE and 1700 BCE. It flourished around the fertile Indus and Saraswathi Rivers. It was rediscovered in 1921. The dates for the Indus Valley civilization, also called the Harappa Civilization have been pushed back to circa 6000 BCE by studies and excavations made in 2016. These studies also concluded that climate change, the previously favored hypothesis, may not have been the cause of its decline.

Discovered in 1922, Mohenjo Daro is one of the largest cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Like other cities from this civilization, it was laid out in a grid pattern and was zoned into residential, industrial, and manufacturing sectors, with a citadel to the west. The narrow streets are edged by drainage gutters at the sides of the thick, high walls of adjacent buildings.

The citadel, situated on a 12-meter high platform (aprox. 40 foot), included a public pool, public gathering space, wells, buildings, and large granaries. The east part of the city was residential. Later phases included gated communities for the elite. Most houses were large and equipped with bathrooms, toilets, and elaborate drainage systems and wells. A workers’ housing complex may indicate the presence of class structures.

Unlike their contemporaries in Egypt and Mesopotamia, they did not build monumental stone structures, or temples and palaces. The largest structures so far uncovered are granaries. The mudbrick walls are in serious danger now due to saltwater seeping up into the walls, causing the bricks to crumble.

The most fascinating and frustrating legacy of this civilization is their still undeciphered script. Thousands of inscribed clay seals have been found, many with a unicorn-like images accompanying the text. Trade goods from and to Mesopotamia and Arabia attest to widespread trade, but similar to Egypt’s earliest eras, they appear to have developed and thrived in isolation.

The Mystery of Lost Cities

Some lost cities have been discovered by chance, and some were discovered after long searches. Some were known and written about in ancient times, leaving clues for modern archaeologists, linguists, and other scholars. Others were forgotten soon after their demise, and never known throughout history thereafter. Some were known by different names through phases of their existence, adding confusion to the mystery of their existence.

This article barely scratches the surface of the list of ancient cities once lost, and later found again. It was a difficult choice because every city has a story to tell — of its founding, the people who lived there, of cultures and achievements, of catastrophes, of good times, of beginnings and endings. What can we learn from them, partly in an effort not to repeat old mistakes?

Imagine the joy of rediscovering such a place— especially for someone who dreamed about it their whole life. Like the retired German banker, Heinrich Schliemann digging with Homer’s Iliad under his arm!

Modern technology, and the cooperation among different disciplines has opened the gates for the discovery of many ancient cities that are still lost. Maybe we will even find Sargon’s elusive Akkad?