As expansion pressed into the United States and Canada and populations of European and European-derived settlers grew, so did the desire to incorporate the entirety of the countries into a singular, “acceptable” way of life, often at the cost of war or forcing people onto reservations. Native Americans were seen as outsiders, “savages,” and a threat. To streamline future endeavors, the governments attempted to start at the root of the “Indian problem”: the children. Thousands of Native children were forced into boarding schools in an attempt to assimilate them into white culture.

Mixed Intentions

Colonel John Chivington, the ruthless conductor of the massacre at Sand Creek, said in 1864, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! Kill and scalp all, big and little…nits make lice.”

This quote perhaps summarizes the ideas that many white Americans and Canadians had about Native Americans at the time: in order for Indigenous people to live peacefully in the same lands as “modern” people, it was necessary to start with the children and alter them before they became full-fledged “Indians.”

Others, often religious in affiliation, considered themselves reformers and wanted to assist Native Americans in becoming members of society so that they could live in harmony with their white counterparts (although many did not take into consideration whether they might actually want to or not).

Education and religion were seen as important tools in these efforts. Therefore, the idea of Native American Boarding Schools was born. Amenable to either motivation, boarding schools accepted children of all ages. They were originally believed to instruct them in a variety of educational intentions and social skills–believed being the keyword.

The Schools Open

Canada has a longer history of residential schools than the United States and opened the doors of their first school in 1831. The first school in the United States was opened in 1860 on the Yakima Reservation in Washington State. While some good-hearted samaritans may have wanted to help Indigenous children by enabling them to adapt to white society, the true intentions of the schools soon became apparent. The schools would become, to an extent, government-funded in both countries by the late nineteenth century, though churches were often affiliated with them as well. Many children were forcibly removed from their homes or promised a better life off the reservation, many of which provided little opportunities for a bright future.

By the 1880s, the United States had 60 schools with over 6,000 children in attendance. In 1900, there were 20,000 “students,” and 25 years later, 60,000. In 1920, the Indian Act in Canada made attendance at these schools compulsory for children from Treaty nations aged 7-15. A treaty nation, both in the United States and Canada, is one that has signed a treaty with the government in question outlining the agreements between them as two sovereign nations.

Richard Henry Pratt: Colonel & Headmaster

Richard Henry Pratt was perhaps one of the most influential figures in the residential school movement. A Civil War veteran, Pratt also fought in conflicts against Native Americans on the US frontier. Pratt encountered many Native Americans during his time in the military, particularly when supervising prisoners.

During this experience, he became interested in “civilizing” Native Americans. This led him to become the founder of the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania in 1879. Though not the first, this was perhaps one of the largest and most famous residential schools in the United States, and many more were modeled after it. Pratt was the school’s headmaster for 25 years and was looked to as a mentor by many others working in the residential school movement.

In 1892, he gave a speech at a conference in Colorado that contained a quote that perhaps best summarizes his efforts and could almost be considered his motto: “Kill the Indian in him to save the man.” Thus, “Killing the Indian” was exactly what the daily routine in these schools set out to do.

Daily Life, Daily Horror

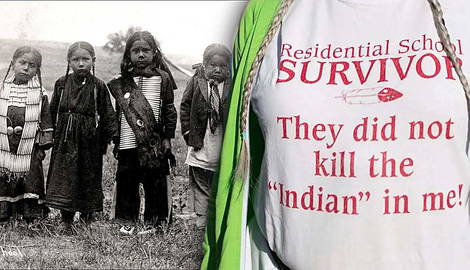

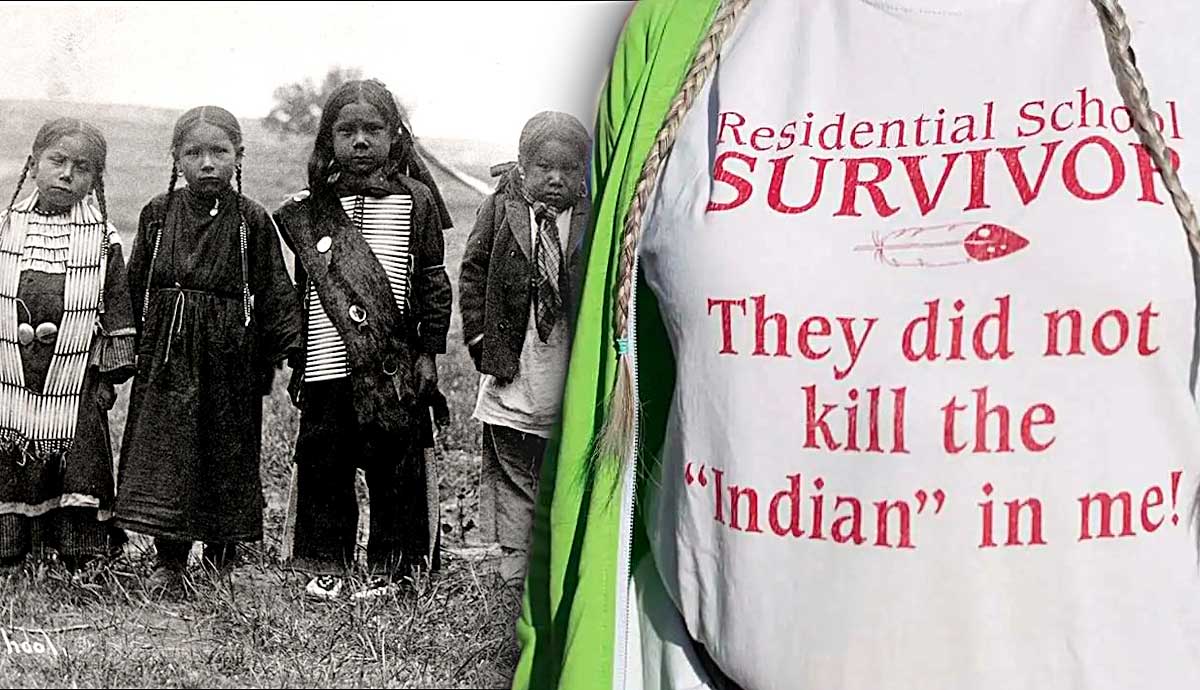

Upon arrival at the residential school, children would be forced to give up their garments for Anglo-style clothing, often school uniforms. Their hair would be cut short. Although culture varies between tribes, long hair is important in many indigenous cultures, often associated with religion or connection to one’s ancestry. Cutting the hair not only changed how the children looked but cut ties with their roots as well.

Children were not allowed to speak their native languages, only English, so communication was impossible or, at the very least, challenging at the beginning of their internment. In many situations, physical punishment would result if students were caught using their Indigenous languages, even by mistake or among one another. Children were not allowed to have any personal belongings reflective of their culture, nor allowed to act in any ways that reflected their nativism. The schools were overcrowded, and nutrition was often poor, conditions ripe for disease, especially among children with little immunity to European illnesses.

The students would attend classes for part of the day, where they were taught English and other school subjects. History was taught with a definitive white bias. Children often had chores they were required to complete, such as helping in the kitchen, working in a school garden, or doing janitorial work such as cleaning bathrooms. Students would learn practical work skills such as sewing and carpentry.

Older children worked in placement programs, where they were essentially rented out to local businesses as hired hands, though they didn’t receive compensation for their work. School officials praised such programs, emphasizing their role in helping the students acclimate to white society. As time went on, industrial programs within the schools grew in scope while the academics were focused on less and less.

Religion was an essential part of the programming at many of the schools, as most were affiliated with some denomination of Christian religion. Many denominations were involved in the residential school movement, from Catholicism to the Protestant faith. Attending church service and converting children away from traditional Native religions was seen as an essential aspect of these programs. It further cut the ties with the children’s original culture and families.

Physical, sexual, verbal, and emotional abuse were all too common at residential schools, a trend that was observable across the United States and Canada. Corporal punishment for the slightest infractions happened daily, and some students even died as a result of the treatment they suffered at the hands of their captors, those who were supposed to be caring for them.

Some children tried to run away but found they were hundreds of miles from home and had no idea where to go. They fell victim to the elements or made it home only to find they were strangers in a strange land, having been isolated from their native culture for too long.

Persistence & Eventual Closure

In the United States, residential schools were in operation until 1978, while in Canada, the final one would not close its doors until 1996. Many of these schools were demolished, seemingly in an effort to erase this embarrassing part of history.

However, recent discovery and recovery efforts of cemeteries and unmarked graves, particularly in Canada, have brought renewed attention to this era. Hundreds of unidentified children are buried at these schools, having died from disease, abuse, and malnutrition, miles away from home, their parents, and their culture.

“Education” as Genocide

When examined as a whole, it becomes clear that the Native American boarding school movements in both the United States and Canada were an attempt by each respective government at cultural genocide, starting with children. These were systematic attempts, funded and supported by the government, to erase entire cultures in order to spread white culture further.

Some villages or reservations refused to send their children to residential schools and banded together in a concerted effort to resist. As a result, their rations from the government were withheld, or police action was taken, thus resulting in physical genocidal actions. It was not until 1978, with the passing of the Indian Child Welfare Act, that Native American parents had a right to say “no” to the removal of their children from their care.

Effects Into the 21st Century

The aftereffects of the boarding schools are still felt today. Recent news coverage has brought new attention to their history, so they are being learned about by the general public, not just those they once affected. It is believed that more graves lie in unknown locations near locations where schools once stood, and the recently unearthed graves are still to be identified.

The relatively recent closings of Native American residential schools means that there are still people alive who were forced to attend these schools and, as a result, live with the trauma of their time there, whether it was the result of being forced from their families or suffering abuse.

Entire cultures have been changed due to the movement in both countries, as generations of children were assimilated or killed, preventing them from learning, practicing, and passing on their traditional cultures. Intergenerational trauma, a psychological phenomenon in which effects of a person’s experienced trauma are experienced by their descendants, is an effect suffered by families of those who spent time at the schools. These children are survivors of genocide, and even today, as adults, they must struggle to understand, retain, and build their personal cultural identities.