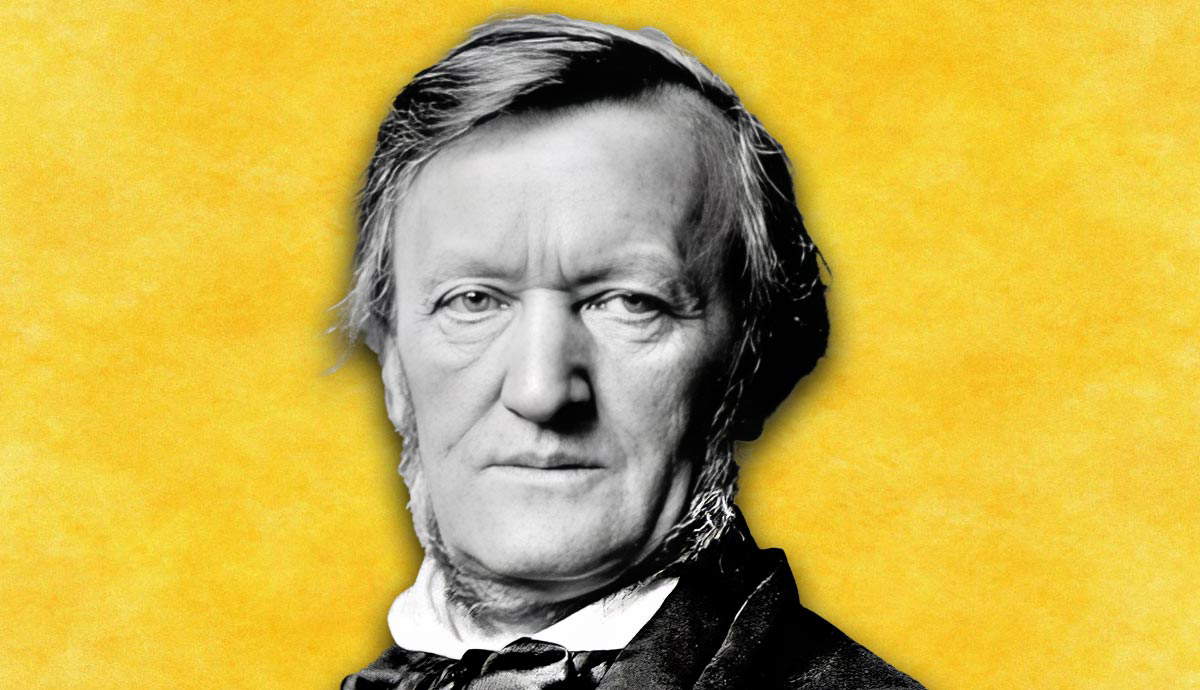

When Hitler descended into the Berlin bunker in 1945, he took a curious item with him – a stack of original Wagnerian scores. Richard Wagner was a longtime idol to Hitler, and the scores were a treasured possession. Throughout his dictatorship, Hitler had held Wagner up as a symbol of German nationalism. Wagner’s operas were ubiquitous in Nazi Germany, and inextricably tied to the project of fascism. Here’s how Hitler co-opted Wagner for his agenda.

Richard Wagner’s Writings and Ideas

Anti-Semitism

Fancying himself a philosopher, Richard Wagner wrote prolifically on music, religion, and politics. Many of his ideas — particularly on German nationalism — foreshadowed Nazi ideology. Wagner was not one to shy away from controversy. An ally of the failed Dresden Uprising, he fled Germany for Zurich in 1849. In the lull of his exile, the loose-tongued composer dipped his toes into philosophy, writing a host of essays.

Most abhorrent of these was Das Judenthum in der Musik (Jewishness in Music). The virulent anti-semitic text attacked two Jewish composers, Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn — both of whom had influenced Wagner deeply. In a tirade, Wagner argued that their music was weak because it was Jewish, and therefore lacked a national style.

In part, Wagner’s scorn was petty. Critics had implied Wagner was copying Meyerbeer, and a resentful Wagner wanted to assert his independence from his Jewish forerunner. It was also opportunistic. At the time, a populist strain of anti-semitism was growing in Germany. Wagner was harnessing this for his own ends.

As the essay later got traction, Meyerbeer’s career stalled. Though he railed against Jewish music until his death, Wagner was not the zealous Jew-hater the Nazis made him out to be. He had close ties with Jewish friends and colleagues, like Hermann Levi, Karl Tausig, and Joseph Rubinstein. And friends, like Franz Liszt, were embarrassed to read his vitriol.

In any case, Richard Wagner’s anti-semitic abuse would be consistent with Nazi ideology some 70 years later.

German Nationalism

In other writings, Richard Wagner declared that German music was superior to any other. Pure and spiritual, he argued, German art was profound where Italian and French music was superficial.

In mid-19th century Europe, nationalism had taken root in the vacuum left by the church. Citizens sought identity in an “imagined community” of shared ethnicity and heritage. And this applied to music too. Composers tried to define the features of their own national style. Wagner was at the helm of this German nationalism. He saw himself as the custodian of German heritage, the natural successor to the titan Beethoven.

And the pinnacle of German music? Opera. Wagner used the plots of his operas to evoke German pride. Most famously, Der Ring des Nibelungen draws heavily on German mythology, while Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg honors the everyman in Nuremberg. Central to his project of nationalism was the Bayreuth Festival.

In the little-known village of Bayreuth, Wagner fashioned a festival that would be devoted to performing his operas. The Festspielhaus architecture was deliberately designed to immerse the audience in the opera. Devotees even took annual “pilgrimages” to the festival, giving it a quasi-religious character.

Bayreuth was the center of German opera, built to showcase how superior German music was. Later, Richard Wagner’s ideology would hit the right chord with the Nazi agenda. His vehement German nationalism and anti-semitism primed him to become a hero of Hitler’s movement.

Hitler’s Love Affair With Wagner

From a young age, Hitler was fascinated with Wagner’s works. Aside from the composer’s beliefs, something in Wagnerian operas spoke to Hitler, and the music aficionado embraced Wagner as an icon.

At 12, Hitler was deeply moved when he first saw Lohengrin performed. In Mein Kampf, he describes his instant affinity with the grandiosity of Wagnerian opera. And allegedly, it was a 1905 performance of Rienzi that triggered his epiphany to pursue a destiny in politics.

Hitler connected to Wagner in an emotive way. In the interwar years, the budding politician sought out Wagner’s family. In 1923, he visited the Wagner house, paid homage to Wagner’s grave, and won the endorsement of his son-in-law, Houston Chamberlain.

Notoriously, he struck up an intimate friendship with Winifred Wagner, who nicknamed him “Wolf.” The composer’s daughter-in-law even sent him the paper on which Mein Kampf was probably written. For whatever reason, Wagner’s music struck an adolescent Hitler. So when Hitler rose to power, he took Richard Wagner along with him. In Hitler’s dictatorship, his personal taste for Wagner naturally became the taste of his party.

Tight Control of Music In Nazi Germany

In Nazi Germany, music had political value. As with every aspect of German society, the state enacted tight measures to control what people could listen to. Music was hijacked by the propaganda apparatus. Goebbels recognized that Kunst und Kultur could be a powerful tool to cultivate Volksgemeinschaft, or community, and help unite a proud Germany.

To do this, the Reichsmusikkammer closely regulated the output of music in Germany. All musicians had to belong to this body. If they wanted to compose freely, they had to co-operate with Nazi directives.

Severe censorship followed. The Nazis purged the music of Jewish composers like Mendelssohn from print or performance. The Expressionist movement was dismantled, the avant-garde atonality of Schoenberg and Berg was seen as a “bacillus.” And in the “Degenerate Art Exhibition,” black music and jazz were castigated.

In droves, musicians fled into exile to protect their artistic freedom from this policy of erasure. Instead, the Reichsmusikkamer promoted “pure” German music. Turning to the past to conjure up a shared heritage, they exalted great German composers like Beethoven, Bruckener — and Richard Wagner.

The Cult of Wagner

The regime championed Richard Wagner as a powerful symbol of German culture. By returning to its roots, they claimed, Germany could restore their stature. And so Wagner became a fixture of important state events, from Hitler’s birthdays to the Nuremberg Rallies. Wagner Societies also sprung up across Germany.

The Bayreuth Festival turned into a spectacle of Nazi propaganda. Frequently, Hitler was a guest, arriving in an elaborate pageantry to resounding applause. Ahead of the 1933 festival, Goebbels broadcast Der Meistersinger, calling it “The most German of all German operas.”

During World War II, Bayreuth was heavily state-sponsored. Despite the raging war, Hitler insisted that it continue into 1945 and bought swathes of tickets for young soldiers (who reluctantly attended lectures on Wagner).

In Dachau, Wagner’s music was played over loudspeakers to “re-educate” political opponents in the camp. And when German troops invaded Paris, some left copies of Wagner’s Parsifal for French musicians to find in their looted homes.

As the Völkischer Beobachter wrote, Richard Wagner had become a national hero. Some also wrote Wagner as an oracle of German nationalism. They speculated that Wagner had predicted historical events like the outbreak of war, the rise of communism, and the “Jewish problem.” In his heroic myths and Teutonic Knights, they teased out an allegory for the Aryan race.

A Professor Werner Kulz called Wagner: “the pathfinder of the German resurrection, since he led us back to the roots of our nature that we find in Germanic mythology.” There were, of course, a few grumbles. Not everyone consented to Wagner being shoved in their faces. Nazis reportedly fell asleep in theaters of Wagner operas. And Hitler could not contend with the public’s taste for popular music.

But officially, the state sanctified Richard Wagner. His operas embodied the ideal of pure German music and became a locus around which nationalism could grow.

Richard Wagner’s Reception Today

Today, it is impossible to play Wagner without conjuring up this loaded history. Performers have grappled with whether it is possible to separate the man from his music. In Israel, Wagner is not played. The last performance of The Meistersinger was canceled in 1938 when news of Kristallnacht broke. Today, in an effort to control public memory, any suggestion of Wagner meets controversy.

But this is hotly debated. Wagner has had his share of Jewish fans, including Daniel Barenboim and James Levine. And then there’s the irony of Theodor Herzl, who listened to Wagner’s Tannhäuser while drafting the founding documents of Zionism.

We could take a page from New Criticism of the early 20th century. This movement encouraged readers (or listeners) to appreciate art for its own sake as if it were outside of history. In this way, we could enjoy a Wagnerian opera, untethered to Wagner’s intentions or his problematic biography.

But it may be impossible to ever wrench Wagner away from this history. After all, it was the same German nationalism that Wagner realized through Bayreuth that would culminate in genocide. The case of Richard Wagner and the Nazis stands as a stark warning against policies of exclusion in the arts today.