The Scythians were a nomadic people of Iranian origins who roamed the Eurasian steppes, across an area spanning from modern-day Kazakhstan to the Ukraine, including the Black Sea Basin, Siberia, and the Caucuses. They were powerful in the region from the 7th to the 4th century BCE. This article will explore their origins, their rise, and their eventual fall.

The Scythians as Indo-European Nomads

There is still much debate as to where the Scythians came from, but fingers seem point toward the Minusinsk hollow, near the River Yenisey Basin, which lies between Krasnoyarsk Krai and the Republics of Khakassia and Tuva in Russia.

According to Cunliffe (2019), “The valley of the Yenisei river, which rises in the eastern Sayan mountains and flows across the vastness of Siberia to the Arctic Ocean, can fairly claim to be the birthplace of the horse-riding hordes that were to dominate the steppe.”

Indeed, around the late 8th century BCE, the hordes known to us as the Scythians show great similarities to local Kurgan burials, while animal depictions in their art are similar to their eastern relatives, the Karasuk culture of the late bronze age.

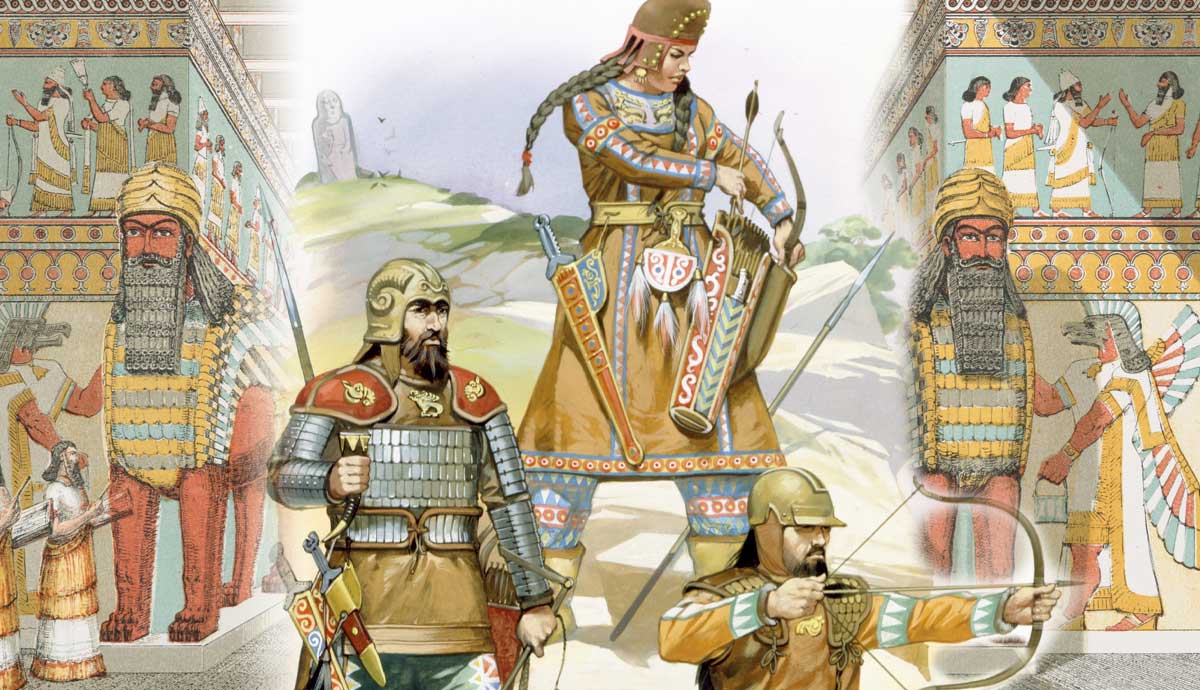

Rising temperatures and better more humid conditions heralded an abundance of grassland in the area, which could support a large population. This steady change carved the way for new generations to start migrating to the west into the Pontic Steppe. In this already populated land, a variety of late bronze age sedentary cultures came under pressure from a nomadic horse-riding people. Battles were fought and many were assimilated by the Scythians who pushed further until they reached the Black Sea Basin. They drove the local Cimmerians out of their land, and they converted this region of the southern Ukraine into a base of operations from which to launch their frequent raids and attacks on Western Asia and the Near East.

“The Scythians did not enter the Near East as farmers looking for good cropland or as diplomats who wanted peaceful relations with the people of the region, but as nomadic warriors intent on plundering and pillaging.”

(River, 2017)

Three Decades of Domination in Western Asia

The Assyrian annals of Esarhaddon are the first source to mention the Scythian invasion of the Near East. They settled in Mannea, to the east of Assyria and they profited from being mercenaries. Some tried to change the political situation in their interest and they were successful in varying degrees for 28 years in both the Near East and Asia Minor.

Esarhaddon king of Assyria (681-669 BCE), was campaigning in Mannea when the Scythian king Ispakaia joined in with his army against the Assyrians. However, Esarhaddon won decisively as one annal tells us: “I trod underfoot the wicked Barnakeans – inhabitants of Til-Assur, who in the [tongue of the people] of Mihranu are named Pitaneans. I scattered the Mannean people, intractable barbarians and I smote with the sword the armies of Ishpakai, the Scythian (Asgusai) – alliance (with them) did not save them.” (Luckenbill, 1989).

It seems Ispakaia was killed in this war and King Bartatua succeeded him. In 672 BCE he asked for Esarhaddon’s daughter Saritrah’s hand in marriage (Ivantchik, 2018). The Assyrians appear to have admired the Scythians martial abilities and an alliance was formed between them against the Urartu Kingdom, centered in what is today Armenia. The Assyrians appear to have seen it as a bigger threat than the Scythians at the time (River, 2017).

The marriage between Bartatua and Saritrah does not appear in Assyrian texts, but a text does showsEsarhaddon asking the oracle of the sun god Shamash about this subject, “Will Bartatua, if he takes my daughter, speak words of true friendship, keep the oath of Asarhaddon, King of Assyria, and do all that is good for Asarhaddon, King of Assyria?” (Cunliffe 2019).

No answer is shown but a close relationship blossomed with Bartatua and (Sulimirski & Taylor, 1991) which suggests that Saritrah might have been the mother of Bartatua’s son Madyes.

After Esarhaddon’s death in 669 BCE, his son Ashurbanipal became the king of Assyria. The honeymoon between the two nations continued under Ashurbanipal reign until the Assyrian King decided to remove Ahshari a puppet king under Scythian influence who ruled Mannaea. From this point on the two parties dissociated from each other, as ones Assyrian text tells us:

“In my fourth campaign I made straight for Ahsheri, king of the Manneans. At the command of Assur, Sin, Shamash, Adad, Bel, Nabu, Ishtar of Nineveh, the queen of Kidmuri, Ishtar of Arbela, Urta, Nergal (and) Nusku, I invaded (lit., entered) the Mannean country and advanced victoriously. His strong cities, together with the small ones, whose number was countless, right up to the city of Izirtua, I captured, I destroyed, I devastated, I burned with fire. People, horses, asses, cattle and sheep, I brought out of those cities and accounted as booty. Ahsheri heard of the advance of my army, forsook Izirtu, his royal city and fled to Ishtatti, a fortress of his and (there) south refuge. . . To save his life he spread forth his hands, beseeching my majesty. Erisinni, a son of his begetting, he dispatched to Nineveh, and he kissed my feet. I had mercy upon him and sent my messengers of peace to him.”

(Luckenbill, 1989)

Losing Grip: The Decline of the Scythians

After the Scythians lost their grip on Mannea, they headed west and brought upon the Assyrians a series of raids throughout the whole of Syria and the Levant. Eventually they reached the Egyptian border, which was until quite recently, part of the Assyrian dominion.

Herodotus says that Psamtek I of Egypt bribed the horde to withdraw back into Syria. The Assyrians were facing troubles from the Babylonians who had been granted their independence and had allied themselves with the Medes under Cyaxares. The remnants of Medea, together with the Neo- Babylonians could have posed a terrifying threat to the Assyrians. However, the Scythians led by Madyes, came to help, and they successfully broke a siege imposed by the allied forces on the Assyrian capital at Nineveh. While there, they defeated the Medes in a pitched battle.

It is true that a victory against the Assyrians was not possible until the Scythians lost their power in Asia. In a classic tale of treachery, this finally happened, according to the story Herodotus tells us:

“During the twenty-eight years of Scythian supremacy in Asia, violence and neglect of law led to absolute chaos. Apart from tribute arbitrarily imposed and forcibly exacted, they behaved like mere robbers, riding up and down the country and seizing people’s property. At last Cyaxares and the Medes invited the greater number of them to a banquet, at which they made them drunk and murdered them, and in this way recovered their former power and dominion. They captured Nineveh and subdued the Assyrians, all except the territory belonging to Babylon.” (Herodotus, The Histories)

The Scythians lost most of their most prominent lords and some of those who survived engaged in the sack of Nineveh alongside the Medes and the Neo-Babylonians. The Assyrians never recovered after that, while the Scythians headed back home north of the Caucasus and upon reaching home they immediately faced problems with their women and children who they had left behind 30 years ago, although it was the veterans who won the day.

“On their return they found an army of no small size prepared to oppose their entrance. For the Scythian women, when they saw that time went on and their husbands did not come back, had intermarried with their slaves…. When therefore the children sprung from these slaves and the Scythian women grew to manhood and understood the circumstances of their birth, they resolved to oppose the army which was returning from Media.”

(Herodotus, The Histories)

Discovering the Scythians

Antiquity has brought forth many fascinating societies and nations, and the Scythians were among these. They were distinctive for their peculiar art, their style of warfare, and their culture. This spotlight on their culture, hopes to erase the shadows of the unknown and bring to light more fascinating stories about their way of life and their history.