The Chinese philosopher Confucius never wrote a book or even wrote down any of his ideas and yet he is one of the most revered and influential philosophers in the world. At times Confucius has reached a godlike status in Chinese culture, a product of posthumous mythologizing and his huge influence on Chinese philosophy, but his teachings remain grounded in human concerns. Like his near-contemporaries Socrates and Siddhartha Gautama, he was interested in how people could live together in harmony and at peace. While Confucius’ ideas span the political and the personal, at their core they are an ethical system based on ritual, virtue, and benevolence.

The Life and Times of Confucius

Confucius was born around 551 BC BC in the Lu province of China. This is modern-day Shangbong in the east of China between Beijing to the north and Shanghai to the south. He grew up in a tumultuous era called the Spring and Autumn period where rival states vied for power after the collapse of the Zhou dynasty some 200 years earlier. It wasn’t all out-war (that came later), but there was a palpable sense of instability, unease and the potential for conflict was never far from the surface.

Confucius was well-educated, coming from a middle-class though impoverished family, and was always eager to learn and study. After holding a variety of official positions, he became an administrator in the Lu court. As his reputation for learning and wisdom grew, he was sought for and gave advice on many topics related to politics, statecraft, and ethics.

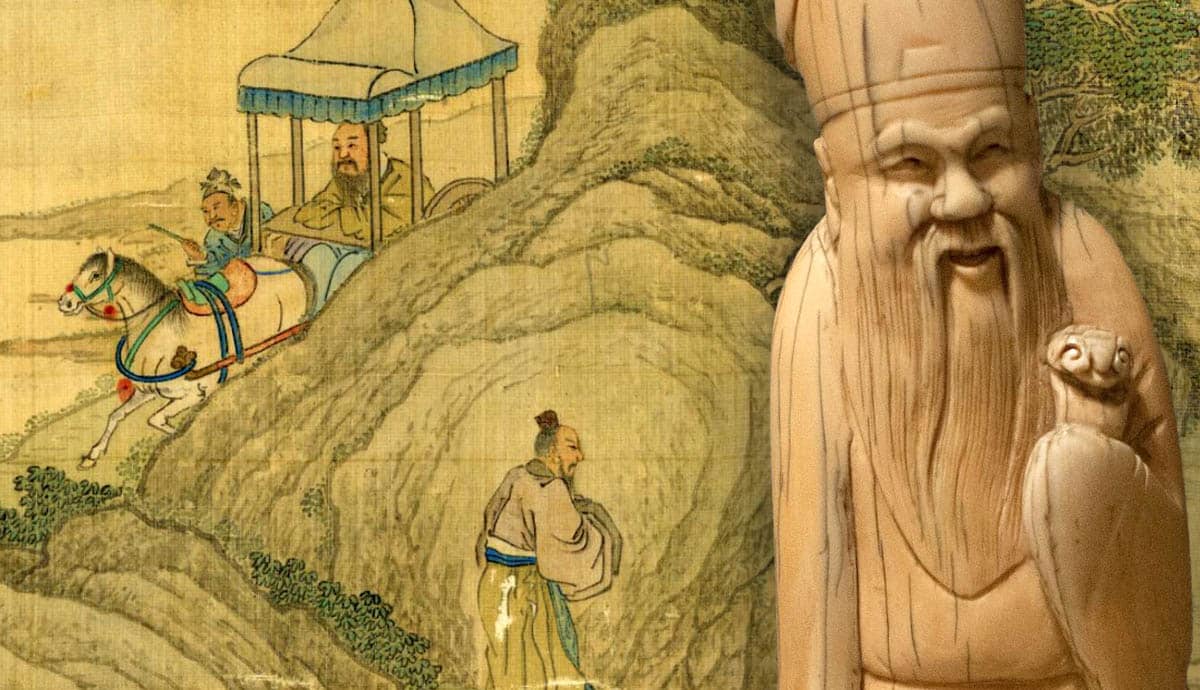

Confucius left the Lu court in disgust at the Duke’s inability to live up to the ideals and obligations of his office. From then on, he seems to have wandered around China teaching and gaining disciples. Eventually, he returned to Lu for several years before dying in 479 BC. It was only then that his students gathered together various fragments and recollections of his teaching into a book we now know as “The Analects”.

The Analects and Why Confucius Didn’t Write Anything

It is an unanswerable question as to why Confucius never wrote any of this teaching down himself despite clearly being able to. However, we can speculate.

One possible reason is that he preferred to teach people in person, believing that the conversation and direct communication between master and pupil was crucial for learning. In addition to that, his teaching was highly contextual and specific to the case at hand. He didn’t feel that any general principles could be passed on devoid of context. And finally, he was adamant that his pupils should think for themselves and not be spoon-fed.

“When I have pointed out one corner of a square to anyone and he does not come back with the other three, I will not point it out to him a second time.”

Analects. 7.8

The Analects then were put together out of fragments that Confucius’ disciples had either written down for themselves or recalled at a later date, so at best they are secondary sources. What is more, there is little mention of the Analects themselves until the Han dynasty, which was after the Warring States period several hundred years after Confucius’ death.

The Han were great librarians, collectors, and editors of knowledge. In many cases, they went so far as to freely edit and add to books that they thought were not good enough by contributing their own ideas. As far as the twenty chapters of the Analects are concerned, these days scholars believe the first fifteen books are a fair reflection of Confucius’ teaching, whereas the last five books are more dubious, possibly due to the interference of a Han librarian.

Nonetheless, the Analects are not only a social and political treatise, but also show that at the heart of Confucius’ teaching is a clear ethical system.

Benevolence: The Center of Confucius’s Philosophy

In his ideas, Confucius was both a conservative and a radical. He borrowed a lot from earlier Chinese philosophy, particularly of the Zhou Dynasty, but reinterpreted and added to it in such a way as to be radical. He talked a lot about following rites and rituals and how to live with virtue, all of which were guided by the principle of benevolence.

For Confucius, the ultimate aim was to be a Gentleman – “Junzi” in Chinese. A Gentleman was someone well educated, well-mannered and wise, someone who knew exactly what was required in the given circumstances, and someone who cultivated the virtues and acted accordingly. Most of all they cultivated and acted with benevolence – “ren” – meaning humaneness or kindness towards other people.

Although Confucius inherited his ideas of virtue from the Zhou, by the time he was teaching they had become vacuous and devoid of meaning. Confucius thought the virtues had great power to transform people’s lives and society. He didn’t believe that the virtues were mandated by heaven for the ruling classes, rather he believed they could be developed by anyone. That Confucius’s ethical system is quiet on matters relating to the gods or spirit world is significant. While he didn’t deny the existence of gods and spirits, he considered them irrelevant. He derived all his ideas from human relationships and his focus was always on how we should treat other people, hence seeking to act with benevolence in all things.

Reciprocity and Virtue in Chinese Philosophy

The four core virtues that Confucius took from the Zhou were reciprocity, filial piety, loyalty and ritual propriety. The most important was reciprocity – “shu” – because it guided everything else and showed someone how to be benevolent. Reciprocity in the moral domain was about following the Golden Rule.

“Chung-kung asked about benevolence. The Master said ‘… Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire…’”

Analects 12.2

It is important to notice that both times Confucius says this in the Analects it is in the negative. Rather than being prescriptive about what you should do, he urges restraint and humility. He asks that you consider the situation you are in and treat people accordingly. This required putting yourself in the other person’s shoes.

Confucius was criticized in later Chinese philosophy for his support of hierarchical social structures. In a sense this is true, he did think social position was important, although he was also subversive of the generally held ideas of status. With regards to reciprocity, the social situation guided you in how to act with benevolence. The key was to consider how you would (not) want to be treated if you were in the other person’s position. For instance, a father should consider how he would want his own father to treat him when dealing with his son, and his son should think in the opposite direction.

The same goes for all other positions and interactions between people, and by acting in this way Confucius believed a better society would be created. Much like Aristotle, he thought that the virtues had to be learned and practiced. Similarly, Confucius understood that moral rules were not fixed or static but dependent on context, requiring deliberation on how to act in each instance. Again, he emphasized the need to think for yourself.

The Place of the Rites and Rituals in Confucius’s Philosophy

A principal reason that many people at the time considered Confucius’ philosophy to be conservative was that he defended rites and rituals passed down from earlier eras. Much of early Chinese Philosophy revolved around rituals. However, much like his apparent support for a social hierarchy, his reasons for encouraging rites and rituals are far more subtle and far more interesting than it might seem.

Confucius thought that it was through the various rituals in life, ranging from everyday manners to funeral rites, that people could be educated in the virtues. He looked beyond the simple actions involved in performing a ritual to the meaning behind it, the lesson it had to teach. In his time Confucius thought that this deeper meaning had been lost and people thoughtlessly went through the motions of ritual without due care, or worse, sloppiness in their execution.

As we have seen, Confucius believed in creating a harmonious society and it was through ritual that this could be achieved. This was because rites and rituals acted as guides to the social norms that oiled the relations between people. In this way rituals were the means to put reciprocity and benevolence into practice through helping to control the emotions and channel them more appropriately. Confucius was usually more concerned that the rituals were done with a sincerity that demonstrated and cultivated internal virtue than about exacting specific actions or rules to follow.

“The Master said, ‘High station filled without indulgent generosity; ceremonies performed without reverence; mourning conducted without sorrow;– wherewith should I contemplate such ways?'”

Analects 3.26

This adherence to rituals was not a fixed code of conduct. Much as Aristotle thought, Confucius believed that people with moral virtue knew the best way to perform a given ritual in a particular context. There was a constant reinterpretation and reapplication of how best to behave because no two situations were the same. Rituals became embodied virtue, a physical manifestation of moral principles; and that was a radical thought for the time.

The Legacy of His Teachings

Almost immediately after Confucius died, China descended into the war and chaos of the 200-year Warring States period. A later philosopher, Mencius, developed and spread Confucian principles, but it wasn’t until the Han established themselves as an imperial power that Confucius’ teachings started to have a wider impact on Chinese philosophy and society, even impacting Daoism and Buddhism.

Neo-Confucianism was developed between the 9th and 12th Centuries. It attempted to remove many of the mystical and superstitious aspects that had become attached to Confucius’s ideas, some of which saw Confucius almost as a deity, and returned it to the more rationalist ethical philosophy that it had started as. It was during this time that Neo-Confucianism spread across much of Asia influencing cultures from Japan to Indonesia in ways that are still palpable today.

Confucius’ philosophy entered into the Western world in the 17th Century thanks to Jesuit missionaries to China. And although not studied as much in the west as the ancient Greek philosophers, his wisdom can still resonate with us today. We have only scratched the surface of what Confucius had to say, but not only does he provide a way into understanding Chinese philosophy and thinking, he can also provide us with plenty of advice on living a good life through ritual, virtue and benevolence.